EPIDEOMOLOGY

Invasive fungal infection is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients. The precise prevalence of disease is not known but population-based surveillance estimates it at 12–17 per 100 000 population.(1,2) Candidosis and aspergillosis remain the most significant problems in the UK. Invasive Candida infections are most commonly seen in critically ill patients in intensive care units (ICUs) and very low birth weight infants. Reported mortality in patients with candidaemia ranges from 36% to 63%, although mortality in ICU patients has decreased in recent years,(3) possibly due to more prompt initiation of antifungal therapy.(4)

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY(5)

Fungal pneumonia

Due to its incidence and morbidity, fungal pneumonia is one of the most severe infections in immunocompromised patients, accounting for 30% of all deaths among BMT recipients.

Pulmonary involvement habitually results from systemic dissemination of the fungus. Large-scale use of antibiotics and prolonged periods of granulocytopenia, as well as corticosteroid therapy, are extremely important factors for the occurrence of fungal infection. Fungi of the genus Aspergillus are the most common causal agents. Other fungi, such as those of the genera Mucor, Fusarium, Rhizopus, Petriellidium, Cryptococcus, Histoplasma, Coccidioides and Candida, have also been identified as causal agents.

Aspergillosis

Invasive aspergillosis is the most common fungal infection among immunocompromised neutropenic patients. In contrast to bacterial infections, caused by cytomegalovirus or by P. jirovecii, in which prophylaxis has been shown to reduce the incidence of these diseases, the number of cases of invasive aspergillosis has increased progressively. According to recent studies, invasive aspergillosis affects 10-15% of BMT recipients. In most cases, aspergillosis affects only the lungs. However, a significant portion of patients develop sinusitis and central nervous system infection. The most common symptoms are cough and dyspnea. However, pleuritic pain and hemoptysis can also occur.

Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia

- jirovecii pneumonia accounted for as much as 10% of all types of pneumonia that affected HIV-negative immunocompromised patients. This incidence plunged after the trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole combination began to be used prophylactically. This form of pneumonia has occurred only in patients who are allergic to sulfa drugs, in patients who do not adhere to the preventive treatment and, occasionally, in patients who become infected before prophylaxis.

Infections caused by Candida spp.

The clinical manifestations of the fungal infections caused by Candida spp. range from localized mucosal infection to dissemination with multiple organ involvement. The immune response is central to the type of infection that these fungi will cause. Impaired cellular immunity is usually associated with infections that are more severe, whereas hematogenous dissemination can occur due to anatomical abnormalities (e.g., patients with heart valve prostheses).

Neutropenic patients can suffer hematogenous dissemination of the fungus via the gastrointestinal tract, as occurs in GVHD.

The following are the major risk factors for the invasive form: a) having a hematological malignancy; b) being the recipient of a solid organ transplant or hematopoietic stem cell transplant; and c) having undergone chemotherapy.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS(6)

Histoplasmosis:

Infection from H capsulatum can result in a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations depending on host immunity and exposure intensity.

- Asymptomatic infection: Occurs in up to 99% of those infected.

- Acute and subacute pulmonary histoplasmosis: Acute infection presents with flu-like symptoms (myalgias, dry cough, fevers, chills, malaise, chest discomfort) for <1 month. Patients may have associated pulmonary infiltrates with focal, diffuse or multinodular pattern. Milder cases may resolve spontaneously but severe cases can progress to respiratory failure or disseminated extrapulmonary infection and are often associated with large exposures.

Subacute form is associated with milder symptoms for more than 1 month. Radiographic findings include focal nodular or patchy infiltrates, and mediastinal/hilar lymphadenopathy.

Both forms may be associated with other inflammatory manifestations such as pleuritis, pericarditis, erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme and polyarthritis.

- Chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis: Patients with underlying lung disease are at risk for developing a chronic form of the infection with productive cough, dyspnea, chest pain, weight loss, hemoptysis, fevers and sweats with symptoms lasting >3 months. Radiographic findings include fibrotic and cavitary apical infiltrates. TB can present similarly and should be excluded.

- Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis: Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis can progress to disseminated infection in patients with immune deficiency (HIV/AIDS, organ transplant, TNF-alpha inhibitor therapy), malignancy, advanced age, and rarely in healthy hosts. Disseminated disease can be life threatening with multiorgan involvement. Findings include pulmonary interstitial or reticulonodular infiltrates, mucosal and skin lesions, lymphadenopathy, cytopenias, transaminitis, hepatosplenomegaly, endocarditis, and meningitis/encephalitis.

- Other pulmonary manifestations

- Lung nodules

- Broncholithiasis: Calcified pulmonary granulomas and lymph nodes can erode into adjacent bronchi resulting in cough, hemoptysis and expectoration of small stones.

- Mediastinal granuloma: Enlarged caseous lymph nodes can cause compression of adjacent structures such as pulmonary vasculature, trachea and pulmonary vessels.

- Fibrosing mediastinitis: Results from excessive fibrotic reaction to histoplasmosis that can lead to compression of mediastinal vessels, esophagus and airways.

Blastomycosis

Blastomycosis can have a wide variety of clinical presentations from asymptomatic to disseminated infection. The most common manifestation is pulmonary disease since the vast majority of exposures occur through an inhalational route. Extrapulmonary disease occurs from hematogenous spread from the primary pulmonary source and can involve, in order of decreasing frequency: skin, bone (osteomyelitis), genitourinary system (prostatitis and epididymoorchitis) and CNS (meningitis, intracranial and epidural abscesses). A characteristic skin finding is an ulcerated or verrucous lesion with irregular borders and purulent discharge.

Pulmonary Manifestations:

- Acute pneumonia: Patients present with symptoms similar to community-acquired pneumonia with productive cough, fevers, weight loss, shortness of breath, and night sweats. CXR findings include alveolar and mass-like infiltrates, though reticulonodular and miliary patterns can also be seen. CT scans can show tree-in-bud opacities, pleural effusions, nodular lesions, or consolidation occasionally with cavitation. Unlike histoplasmosis, significant hilar lymphadenopathy is not present, which can help distinguish between the two endemic mycoses.

- Chronic pneumonia: Patients may present with a chronic form that may be in distinguishable from other fungal infections, TB, and malignancy. Symptoms include fevers, weight loss, chest pain, productive cough, and hemoptysis. Common radiographic findings are fibronodular infiltrates, mass-like opacities than can mimic bronchogenic carcinoma, and alveolar infiltrates. Upper lobe lesions are more frequent and pleural effusion and pleural thickening may also be present.

- ARDS: In rare cases, patients may present with diffuse pulmonary infiltrates and ARDS, associated with a very high mortality. It is unclear whether this form occurs due to high fungal burden or poor host immune response.

Coccidioidomycosis

The majority of coccidioidomycosis infections are thought to be subclinical. A fraction of patients with pulmonary infection develops extrapulmonary disseminated infection with the most common sites involving skin (granulomatous lesions, abscess), bones, joints, and meninges. An LP should be performed on all patients with primary infection and headache, blurry vision, or any other neurologic symptoms.

Pulmonary Manifestations:

- Primary infection: aka Valley fever; accounts for up to 1/3 of community-acquired pneumonia in endemic areas, and presents with cough, fatigue, fevers and chills. Patients may have accompanying erythema nodosum and exanthem similar to erythema multiforme, both of which usually indicate a favorable prognosis. Radiographic findings may be unremarkable in up to 1/2 of patients or show lobar infiltrate and ipsilateral hilar adenopathy. Up to 15% may develop pleural effusions with lymphocytic and eosinophilic predominance. Rare cases of acute respiratory failure and ARDS have been reported. This may occur in patients with underlying immune compromise such as HIV/AIDS or those with massive fungal exposure.

- Residual pulmonary nodules: In a small fraction of patients with primary infection, infiltrates do not resolve completely, and they are left with solitary pulmonary nodules often in the peripheral lung. Malignancy should be considered in the differential.

- Cavities: Residual thin walled cavities may develop from primary infection and are often asymptomatic. Rarely these cavities can rupture into the pleural cavity forming a bronchopleural fistula and pneumothorax. A ruptured cavity can present as the initial manifestation of Coccidioidesin some patients with chest pain and dyspnea, and are not associated with immunosuppression. In some patients, especially diabetics, primary infection can remain unresolved and evolve into chronic fibrocavitary pneumonia.

- Diffuse reticulonodular pneumonia: Develops in patients with cellular immune deficiency or large exposures. It results from fungemia leading to septic emboli and patient presents with severe dyspnea, fevers and night sweats.

Cryptococcosis

The most common and serious manifestation of cryptococcosis is meningitis. Additional sites of infection include lungs, skin, prostate, bone and eyes. The spectrum of clinical manifestations ranges from colonization to asymptomatic infection to severe pneumonia and respiratory failure.

- Colonization may be seen in patients with underlying structural lung disease.

- In immune competent hosts with exposure, subclinical infections are common and most are asymptomatic. Infections often are found incidentally with diagnostic evaluation of pulmonary nodules. Symptomatic infection is associated with cough, chest pain, fevers, malaise, sputum production, and hemoptysis. Radiographic findings include non-calcified pulmonary nodules, masses, consolidation, cavities, mediastinal/hilar lymphadenopathy, and interstitial pneumonitis.

- Immunocompromised patients are generally more symptomatic, have more severe radiographic findings, and are more likely to present with extrapulmonary disease. The majority of these infections are likely from reactivation of latent disease. ARDS is most likely to occur with organ transplant recipients and is associated with high mortality.

- The severity and extent of disseminated infection in HIV patients correlates inversely with CD4 counts. The majority of HIV patients with pulmonary cryptococcosis will have CNS involvement.

Aspergillosis

Aspergillus causes a wide spectrum of clinical manifestation based on host immune status. Extrapulmonary disease can occur and manifests as invasive sinus disease, tracheobronchial aspergillosis, endocarditis and myocarditis, osteomyelitis and septic arthritis, endopthalmitis and keratitis, cutaneous disease, peritonitis and CNS aspergillosis

Below lists the pulmonary disease presentations in order of increasing invasiveness in the setting of increasing immune suppression.

- Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA): Hypersensitivity reaction in response to airway colonization with Aspergillus. Most commonly seen in patients with asthma and cystic fibrosis.

- Aspergilloma: Formation of fungal ball composed of Aspergillushyphae, mucous, fibrin and cellular debris within a prior cavity from COPD, sarcoidosis or TB. The typical radiographic finding is a freely moving solid mass within a cavity. Aspergillomas are often asymptomatic but may present with cough and rarely life threatening hemoptysis.

- Chronic necrotizing and chronic cavitary aspergillosis: Semi-invasive form in patients with normal to some degree of immune deficiency, associated with cavitary lung lesion. Cavities may be thin walled or may be a consolidation with areas of cavitation.

- Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA): Commonly presents with fevers, hemoptysis and pleuritic chest pain. Aspergillus fumigatus is the most common species in IPA. The classic presentation is a pulmonary nodule that develops in a neutropenic patient. This lesion can expand and evoke localized inflammation and hemorrhage, creating a radiographic “halo sign” before ultimately cavitating, which largely occurs after resolution of neutropenia concurrent with tissue necrosis forming an air-crescent sign. Radiographic findings are variable and include nodules +/- cavitation, patchy or segmental consolidation, tree-in-bud opacities and ground glass opacities

Pneumocystis Pneumonia (PCP)

Clinical manifestations of PCP in HIV differ from that of patients with other immune deficiencies. PCP in HIV usually presents with an insidious onset of dry cough, progressive dyspnea, weight loss, and fever. Acute dyspnea and chest pain should raise suspicion for a pneumothorax. Immunocompromised patients without HIV typically present with acute and fulminant respiratory failure usually in the setting of a change in immunosuppression. Most patients have hypoxemia and increased alveolar-arterial (A-a) oxygen gradient on presentation.

CXR may be unremarkable in early mild disease and chest CT may be helpful in these cases. Most common findings are bilateral diffuse ground glass and interstitial infiltrates +/- consolidation, extending from the perihilar region. Less common findings are nodules that may cavitate, lobar infiltrates, pneumatocele, and occasionally pneumothorax.

Although rare, dissemination to extra-pulmonary sites, including the lymph nodes, spleen, liver, and bone marrow may occur in patients on aerozolized pentamidine prophylaxis or those with advanced HIV not on prophylaxis.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS(6)

Histoplasmosis

In patients with clinical and radiographic suspicion for histoplasmosis, diagnosis can be supported with Histoplasma antigen and antibody detection, fungal cultures and histopathology. Cultures and antigen tests are usually negative in those with broncholithiasis, lung nodules, mediastinal granuloma, and fibrosing mediastinitis.

- Histoplasmaantigen: Can be detected in blood, urine, CSF, or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid. Highest diagnostic yield results from testing both urine and serum. Up to 83% with acute pulmonary histoplasmosis have positive antigens. BAL antigen also improves diagnostic yield in pulmonary histoplasmosis though antigen cross reactivity can be seen with other endemic mycoses.

- PCR assays: Less sensitive than microscopic examination or antigen detection and of uncertain utility.

- Serum antibodies: Peak about a month after infection and often negative earlier in the course of the disease. Sensitivities are up to 89% for localized pulmonary infection, up to 90% for chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis and up to 80% for disseminated disease. Antibodies can be falsely negative in immunosuppressed patients. It can also remain positive for several years and may not represent active disease.

- Fungal cultures: From sputum, tissue or BAL and most helpful in patients with chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis though may require up to 6 weeks for growth. Blood cultures can be also positive in patients with disseminated disease.

- Histopathology and cytology (BAL): Findings include caseating granulomas and yeast with narrow-based budding.

Blastomycosis

Diagnosis of blastomycosis involves high index of clinical suspicion and definitive diagnosis requires clinical specimen with growth of B dermatitidis.

- Cultures: A positive culture result is the gold standard. Sputum and BAL cultures are associated with high diagnostic yield.

- Direct examination: Though of relatively low diagnostic yield, KOH preparation of clinical specimens (skin scraping/drainage, sputum, BAL, CSF, urine, etc.) can show characteristic broad-based budding yeast. Direct visualization in the appropriate clinical setting can justify starting empiric antifungals while awaiting culture confirmation.

- Serologic testing: Not helpful in diagnosis because of low sensitivity and specificity as well as cross-reactivity with other endemic mycosis.

- Antigen testing: has limited utility in diagnosis of blastomycosis.

Coccidioidomycosis

Diagnosis of symptomatic coccidioidomycosis relies on a history of exposure and appropriate clinical and radiographic presentation. Several tests can assist with establishing a diagnosis including culture, histopathology, or serologic testing. Antigen testing has poor sensitivity but may be useful in immunocompromised patients or to monitor response to therapy.

- Serologic testing: EIA for IgG or IgM are ordered as screening tests, and if positive, confirmatory immunodiffusion assay can be completed. A complement fixation titer can also be obtained which can help in determining the severity of disease.

- Culture: Coccidioidesgrowth does not require special media and can be isolated from sputum, skin lesions, and rarely blood samples. When clinically suspected, laboratory staff should be alerted since exposure can lead to infection in laboratory personnel.

- Histopathology: Coccidioidesspherules are the common form seen in tissue samples.

- Other findings: Peripheral eosinophilia may be seen in up to 1/4 of patients.

Cryptococcosis

Diagnosis of cryptococcosis relies on isolation of the pathogen from a respiratory specimen in the appropriate clinical setting. Diagnostic tools in addition to imaging includes fungal cultures, histopathology and serum cryptococcal antigen. Immunocompromised patients with pulmonary disease should be evaluated for disseminated disease with blood and CSF cryptococcal antigen and fungal cultures.

- Fungal culture and histology: Isolation and growth of encapsulated yeast form in sputum, BAL fluid, blood, and tissue samples are diagnostic in the appropriate setting. Biopsy of asymptomatic nodules can show yeast form but cultures may be negative.

- Serum cryptococcal antigen: Associated with high sensitivity/specificity in immunocompromised hosts and disseminated disease but its utility is limited in immune competent patients with isolated pulmonary disease. Serum titers during therapy do not correlate with response to therapy. BAL and sputum antigen titers are not useful.

- LP: Should be performed in all patients with disseminated disease, neurologic symptoms or positive serum antigen titers to evaluate for cryptococcal meningitis.

Aspergillosis

Definitive diagnosis of aspergillosis involves growth of Aspergillus species in culture, and in IPA, evidence of tissue invasion by fungal hyphae on pathology. Non-invasive modalities are available to aid in the diagnosis since biopsy may not be always feasible.

- Bronchoscopy with BAL should be performed in cases of suspected IPA. In general transbronchial biopsies are not recommended given their low yield and bleeding risk. BAL diagnostic yield varies with radiographic lesions and with consolidative opacities and tree-in-bud abnormalities, yields are close to 70%.

- Serum 1-3-beta-D-glucan (cell wall component) or Fungitell assay is recommended by guidelines for diagnosis of IPA in high-risk patients. This assay is not specific for Aspergillus and can be positive in other fungal infections. False positives can also occur with antibiotic use such as with ampicillin-sulbactam and carbapenems.

- BAL galactomannan (polysaccharide cell wall component) is also recommended as a marker for IPA in the appropriate clinical setting. False positives occur with certain antibiotics such as pipercillin-tazobactam and in patients with other invasive mycoses. BAL galactomannan sensitivities exceed 70%.

- PCR assays have showed mixed results and are currently not recommended.

- Histopathology in the setting of invasive disease will demonstrate characteristic septated fungal hyphae with 45° branching.

Pneumocystis Pneumonia (PCP)

Since Pneumocystis cannot be grown in culture, establishing a definitive diagnosis of PCP requires visualization of organism in cysts or trophic form from respiratory specimens or PCR.

- Induced sputum: Variable sensitivity but sensitivity approaches 100%.

- BAL: Next step if sputum nondiagnostic or unobtainable; has high sensitivity with yield increased with multiple lobes sampled; transbronchial biopsies can be considered (yields up to 100%) in patients receiving aerosolized pentamidine since this lowers BAL yield.

- Transthoracic or open lung biopsy: Can be considered in patients with nondiagnostic sputum, BAL and transbronchial biopsies; up to 100% sensitivity and specificity but significant risks associated with the procedure should be weighed against the benefits.

- PCR assays: Of respiratory secretions, BAL, blood or tissue samples can increase diagnostic yield especially in non-HIV immunocompromised patients.

- Other labs:

- 1-3-beta-D-glucan: Serum levels present in Pneumocystis cell wall and can be used with clinical findings to make a presumptive diagnosis of PCP when definitive diagnosis cannot be made; also elevated in histoplasmosis, candida infections, and aspergillosis.

LDH: Levels usually elevated but not useful in differentiating PCP from other diseases.

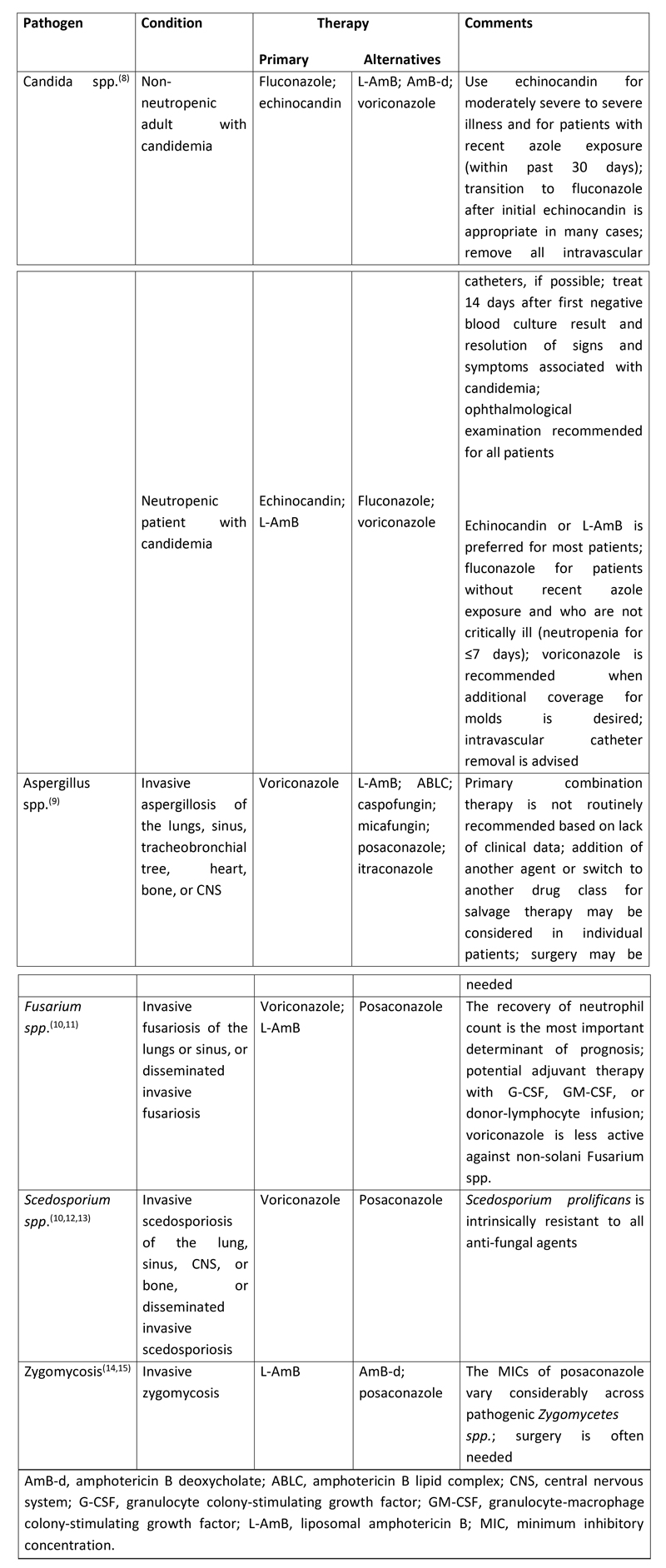

TREATMENT OPTIONS

The management of invasive fungal infections begins with a high index of suspicion and prompt diagnosis. Clearly the early initiation of antifungal therapy is a major contributor to enhanced survival. Reducing immunosuppression whenever possible with prompt initiation of appropriate antifungal therapy (monotherapy or combination) (Table 1) remains the mainstay for the treatment of invasive fungal infections. However, rapid reduction of immunosuppressive therapy in conjunction with initiation of antifungal therapy in solid-organ transplant recipients may lead to the development of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, the clinical manifestations of which mimic worsening disease.(7) Reversal of neutropenia with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor or granulocyte infusions may be used to hasten recovery from neutropenia.

Table 1. Pharmacologic therapy against common invasive fungal pathogens in immunocompromised patients

Surgery may be required depending on the type of invasive fungal infection. Recommendations for surgery may be considered in patients with invasive aspergillosis who have a solitary lung lesion before chemotherapy or HSCT, those with hemoptysis from a lung lesion, those with disease that invades the chest wall, or situations where the infection involves the pericardium or great vessels.(9) For zygomycosis, surgery is often required in addition to antifungal therapy.

GOALS OF THERAPY

The goals of treating antifungal infections are to provide the patient with symptomatic relief, successfully eliminate infection, and prevent recurrence of infections.

GUIDELINES

To view, “An Official American Thoracic Society Statement: Treatment of Fungal Infections in Adult Pulmonary and Critical Care Patients”, please click on below link:

https://www.thoracic.org/statements/resources/tb-opi/treatment-of-fungal-infections-in-adult-pulmonary-critical-care-and-sleep-medicine.pdf

To view, “The 2015 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines for the management of fungal infections in mechanical circulatory support and cardiothoracic organ transplant recipients: Executive summary”, please click on below link:

https://www.jhltonline.org/article/S1053-2498(16)00054-1/pdf

To view, “Canadian Pediatric society – Antifungal agents for the treatment of systemic fungal infections in children”, please click on below link:

https://www.cps.ca/documents/position/antifungal-agents-fungal-infections

PREVENTION(16)

General measures

Several measures can be taken with high-risk patients to reduce their exposure to fungi; in general, these measures are not realistic for outpatients. Housing inpatients in the appropriate protective environment is important and HEPA filtration can reduce the risk of infection by airborne spores. Isolation in HEPA-filtered rooms is restricted to allogeneic BMT recipients in some centres, with autologous BMT recipients and acute myeloid leukaemia patients receiving high-dose chemotherapy in four-bed bays. Good housekeeping procedures and handwashing compliance by healthcare workers reduce the risk of transferring yeasts to patients.

Seasonal variation in spore counts, although documented in some studies, has not been firmly established but both high air counts and outbreaks of invasive aspergillosis have been linked with building work in the vicinity. Limiting the number of visitors (who are also potential carriers of fungi) may also be of value. However, preventive measures that exceed established nursing hygiene standards do not appear to reduce further the incidence of fungal infections. Regular damp dusting of rooms will ensure that any spores that settle will be removed and thus help to reduce exposure. It is this physical removal that is more important than any inhibitory cleansing agent. Damp dusting may be considered an ineffective use of nursing time but cleaning of some electrical equipment requires special knowledge and allows nurses to interact with patients and reduces the patients’ perception that they see medical staff only during an invasive procedure. Encouraging willing relatives to participate in damp dusting may also be psychologically helpful for the relatives and the patient.

Excluding carpets, flowers, potted plants and certain foods from the patient’s environment and ensuring that the hospital water supply is not contaminated also help to protect patients from infection. Cases of dietary exposure to Aspergillus spp. in processed foods that subsequently led to infection in neutropenic patients have been recorded. The need for certain dietary exclusions in high-risk patients is a policy that often needs careful explaining to staff, patients and visitors. An important aspect of prevention is to treat the patient as an individual. Nurses usually spend more time with patients than any other healthcare professional and can therefore identify specific risks to individual patients (such as those related to occupation or hobbies).

Chemoprophylaxis

Preventive therapy of a vulnerable patient population, identified by risk assessment and surveillance, is used to reduce the incidence of systemic fungal infection and the need for empirical therapy. Allogeneic BMT recipients usually receive prophylaxis before starting chemotherapy because of the high likelihood of neutropenia during treatment.

By contrast, autologous BMT recipients tend to receive prophylaxis only when they become neutropenic because pretransplant immunosuppression is not administered, and not all patients develop prolonged deep neutropenia. Prophylaxis continues until the patient’s immune system recovers or graft vs. host disease (GVHD) recedes or until prevention is thought to have failed and empirical therapy is initiated.

REFERENCES

- Lamagni TL, Evans BG, Shigematsu M, et al. Emerging trends in the epidemiology of invasive mycoses in England and Wales (1990–9), Epidemiol Infect , 2001, vol. 126 (pg. 397-414)

- Kibbler CC, Seaton S, Barnes RA, et al. Management and outcome of bloodstream infections due to Candida species in England and Wales, J Hosp Infect , 2003, vol. 54 (pg. 18-24)

- Blot SI, Vandewoude KH, Hoste EA, et al. Effects of nosocomial candidemia on outcomes of critically ill patients, Am J Med , 2003, vol. 113 (pg. 480-5)

- Blot SI, Hoste EA, Vandewoude KH, et al. Estimates of attributable mortality of systemic Candida infection in the ICU, J Crit Care , 2003, vol. 18 (pg. 130-1)

- Silva RF. Fungal infections in immunocompromised patients. Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia. 2010 Feb;36(1):142-7.

- Tessy Paul. Fungal Infections (including PCP). Available from: https://www.clinicaladvisor.com/pulmonary-medicine/fungal-infections-including-pcp/article/626170/ (Accessed on 2019 Feb 06)

- Singh N, Lortholary O, Alexander BD, Gupta KL, John GT, Pursell K, Munoz P, Klintmalm GB, Stosor V, del Busto R, Limaye AP, Somani J, Lyon M, Houston S, House AA, Pruett TL, Orloff S, Humar A, Dowdy L, Garcia-Diaz J, Kalil AC, Fisher RA, Husain S; Cryptococcal Collaborative Transplant Study Group: An immune reconstitution syndrome-like illness associated with Cryptococcus neoformans infection in organ transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2005, 40:1756–61.

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, Benjamin DK, Calandra TF, Edwards JE, Filler SG, Fisher JF, Kullberg BJ, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Reboli AC, Rex JH, Walsh TJ, Sobel JD: Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009, 48:503–35.

- Walsh TJ, Anaissie EJ, Denning DW, Herbrecht R, Kontoyiannis DP, Marr KA, Morrison VA, Segal BH, Steinbach WJ, Stevens DA, van Burik JA, Wingard JR, Patterson TF; Infectious Diseases Society of America: Treatment of aspergillosis: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008, 46:327–60.

- Perfect JR, Marr KA, Walsh TJ, Greenberg RN, DuPont B, de la Torre-Cisneros J, Just-Nübling G, Schlamm HT, Lutsar I, Espinel-Ingroff A, Johnson E: Voriconazole treatment for less-common, emerging, or refractory fungal infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2003, 36:1122–31.

- Kontoyiannis DP, Bodey GP, Hanna H, Hachem R, Boktour M, Girgaway E, Mardani M, Raad II: Outcome determinants of fusariosis in a tertiary care cancer center: the impact of neutrophil recovery. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004, 45:139–41.

- Troke P, Aguirrebengoa K, Arteaga C, Ellis D, Heath CD, Lutsar I, Rovira M, Nguyen Q, Slavin M, Chen SC; Global Scedosporium Study Group: Treatment of scedosporiosis with voriconazole: clinical experience with 107 patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008, 52:1743–50.

- Caira M, Girmenia C, Valentini CG, Sanguinetti M, Bonini A, Rossi G, Fianchi L, Leone G, Pagano L: Scedosporiosis in patients with acute leukemia: a retrospective multicenter report. Haematologica. 2008, 93:104–10.

- Spellberg B, Walsh TJ, Kontonyiannis DP, Edwards J, Ibrahim AS: Recent advances in the management of mucormycosis: from bench to bedside. Clin Infect Dis. 2009, 48:1743–51.

- van Burik JA, Hare RS, Solomon HF, Corrado ML, Kontoyiannis DP: Posaconazole is effective as salvage therapy in zygomycosis: a retrospective summary of 91 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2006, 42:e61–5.

- Johnson EM, Gilmore M, Newman J, Stephens M. Preventing fungal infections in immunocompromised patients. British Journal of Nursing. 2000 Sep 28;9(17):1154-64.