BACKGROUND

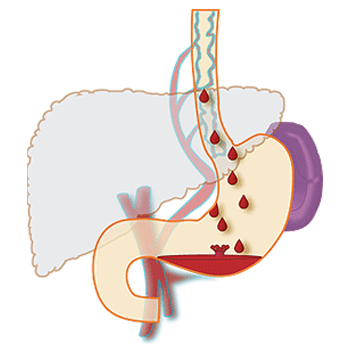

Esophageal varices are abnormal, enlarged veins in the tube that connects the throat and stomach (esophagus). This condition occurs most often in people with serious liver diseases.

Esophageal varices develop when normal blood flow to the liver is blocked by a clot or scar tissue in the liver. To go around the blockages, blood flows into smaller blood vessels that aren’t designed to carry large volumes of blood. The vessels can leak blood or even rupture, causing life-threatening bleeding.

A number of drugs and medical procedures can help prevent and stop bleeding from esophageal varices.

DISEASE OCCURRENCE IN POPULATION

Cirrhosis affects 3.6 out of every 1000 adults in North America, and is responsible for more than one million days of work-loss and 32,000 deaths annually. A major cause of cirrhosis-related morbidity and mortality is the development of variceal hemorrhage, a direct consequence of portal hypertension. Each episode of active variceal hemorrhage is associated with 30 percent mortality. In addition, survivors of an episode of active bleeding have a 70 percent risk of recurrent hemorrhage within one year of the bleeding episode.

Variceal hemorrhage occurs in 25 to 40 percent of patients with cirrhosis. While several modalities are available for primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding, many are associated with significant adverse effects.

According to one study conducted in Pakistan, esophageal varices (53%) have been found the major cause of bleeding followed by duodenal ulcer (12%) and gastric ulcer (14%).

DISEASE OCCURRENCE IN POPULATION

Cirrhosis affects 3.6 out of every 1000 adults in North America, and is responsible for more than one million days of work-loss and 32,000 deaths annually. A major cause of cirrhosis-related morbidity and mortality is the development of variceal hemorrhage, a direct consequence of portal hypertension. Each episode of active variceal hemorrhage is associated with 30 percent mortality. In addition, survivors of an episode of active bleeding have a 70 percent risk of recurrent hemorrhage within one year of the bleeding episode.

Variceal hemorrhage occurs in 25 to 40 percent of patients with cirrhosis. While several modalities are available for primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding, many are associated with significant adverse effects.

According to one study conducted in Pakistan, esophageal varices (53%) have been found the major cause of bleeding followed by duodenal ulcer (12%) and gastric ulcer (14%).

RISK FACTORS

Although many people with advanced liver disease develop esophageal varices, most won’t have bleeding. Varices are more likely to bleed if you have:

- High portal vein pressure: The risk of bleeding increases with the amount of pressure in the portal vein (portal hypertension).

- Large varices: The larger the varices, the more likely they are to bleed.

- Red marks on the varices: When viewed through an endoscope passed down your throat, some varices show long, red streaks or red spots. These marks indicate a high risk of bleeding.

- Severe cirrhosis or liver failure: Most often, the more severe your liver disease, the more likely varices are to bleed.

- Continued alcohol use: Your risk of variceal bleeding is far greater if you continue to drink than if you stop, especially if your disease is alcohol related.

SIGN AND SYMPTOMS

Esophageal varices usually don’t cause signs and symptoms unless they bleed. Signs and symptoms of bleeding esophageal varices include:

- Vomiting and seeing significant amounts of blood in your vomit

- Black, tarry or bloody stools

- Lightheadedness

- Low blood pressure

- Rapid heart rate

- Loss of consciousness (in severe case)

Your doctor might suspect varices if you have signs of liver disease, including:

- Yellow coloration of your skin and eyes (jaundice)

- Easy bleeding or bruising

- Fluid buildup in your abdomen (ascites)

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

If you have cirrhosis, your doctor should screen you for esophageal varices when you’re diagnosed. How often you’ll undergo screening tests depends on your condition. Main tests used to diagnose esophageal varices are:

- Endoscope exam: A procedure called upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is the preferred method of screening for varices. Your doctor inserts a thin, flexible, lighted tube (endoscope) through your mouth and into your esophagus, stomach and the beginning of your small intestine (duodenum).

The doctor will look for dilated veins, measure them, if found, and check for red streaks and red spots, which usually indicate a significant risk of bleeding. Treatment can be performed during the exam.

- Imaging tests: Both abdominal CT scans and Doppler ultrasounds of the splenic and portal veins can suggest the presence of esophageal varices.

- Capsule endoscopy: In this test, you swallow a vitamin-sized capsule containing a tiny camera, which takes pictures of the esophagus as it goes through your digestive tract. This might be an option for people who are unable or unwilling to have an endoscope exam. This technology is more expensive than regular endoscopy and not as available.

TREATMENT

The primary aim in treating esophageal varices is to prevent bleeding. Bleeding esophageal varices are life-threatening. If bleeding occurs, treatments are available to try to stop the bleeding.

Treatment to prevent bleeding

Treatments to lower blood pressure in the portal vein may reduce the risk of bleeding esophageal varices. Treatments may include:

- Medications to reduce pressure in the portal vein: A type of blood pressure drug called a beta blocker may help reduce blood pressure in your portal vein, decreasing the likelihood of bleeding. These medications include propranolol and nadolol.

- Using elastic bands to tie off bleeding veins: If your esophageal varices appear to have a high risk of bleeding, your doctor might recommend a procedure called band ligation.

Using an endoscope, the doctor snares the varices and wraps them with an elastic band, which essentially “strangles” the veins so they can’t bleed. Esophageal band ligation carries a small risk of complications, such as scarring of the esophagus.

Treatment if you’re bleeding

Bleeding varices are life-threatening, and immediate treatment is essential. Treatments used to stop bleeding and reverse the effects of blood loss include:

- Using elastic bands to tie off bleeding veins.

- Medications to slow blood flow into the portal vein: A drug called octreotide is often used with endoscopic therapy to slow the flow of blood from internal organs to the portal vein. The drug is usually continued for five days after a bleeding episode.

- Diverting blood flow away from the portal vein: Your doctor might recommend a procedure called transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) to place a shunt. The shunt is a small tube that is placed between the portal vein and the hepatic vein, which carries blood from your liver to your heart. The shunt reduces pressure in the portal vein and often stops bleeding from esophageal varices.

But TIPS can cause serious complications, including liver failure and mental confusion, which can develop when toxins that the liver normally would filter are passed through the shunt directly into the bloodstream. TIPS is mainly used when all other treatments have failed or as a temporary measure in people awaiting a liver transplant.

- Restoring blood volume: You might be given a transfusion to replace lost blood and clotting factor to stop bleeding.

- Preventing infection: There is an increased risk of infection with bleeding, so you’ll likely be given an antibiotic to prevent infection.

- Replacing the diseased liver with a healthy one: Liver transplant is an option for people with severe liver disease or those who experience recurrent bleeding of esophageal varices. Although liver transplantation is often successful, the number of people awaiting transplants far outnumbers the available organs.

- Sclerotherapy: A gastroenterologist directly injects the varices with a blood-clotting solution instead of banding them.

- Devascularization: A surgical procedure that removes the bleeding varices. This procedure is done when a TIPS or a surgical shunt isn’t possible or unsuccessful in controlling the bleeding.

- Esophageal transection: A surgical procedure in which the esophagus is cut through and then stapled back together after the varicies have been tied off. Sometimes there is bleeding at the staple line.

Rebleeding

Bleeding will recur in most people who have bleeding from esophageal varices. Beta blockers and esophageal band ligation are the recommended treatments to help prevent rebleeding.

PRECAUTIONS

Currently, no treatment can prevent the development of esophageal varices in people with cirrhosis. While beta blocker drugs are effective in preventing bleeding in many people who have esophageal varices, they do not prevent esophageal varices from forming.

Advice following preventions to patient:

- Don’t drink alcohol: People with liver disease are often advised to stop drinking alcohol, since the liver processes alcohol. Drinking alcohol may stress an already vulnerable liver.

- Eat a healthy diet: Choose a plant-based diet that’s full of fruits and vegetables. Select whole grains and lean sources of protein. Reduce the amount of fatty and fried foods you eat.

- Maintain a healthy weight: An excess amount of body fat can damage your liver. Obesity is associated with a greater risk of complications of cirrhosis. Lose weight if you are obese or overweight.

- Use chemicals sparingly and carefully: Follow the directions on household chemicals, such as cleaning supplies and insect sprays. If you work around chemicals, follow all safety precautions. Your liver removes toxins from your body, so give it a break by limiting the amount of toxins it must process.

- Reduce your risk of hepatitis: Sharing needles and having unprotected sex can increase your risk of hepatitis B and C. Protect yourself by abstaining from sex or using a condom if you choose to have sex. Ask your doctor whether you should be vaccinated for hepatitis B and hepatitis A.

REFERENCES

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/esophageal-varices/symptoms-causes/syc-20351538

- Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J. Management of varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:823.

- Smith JL, Graham DY. Variceal hemorrhage: a critical evaluation of survival analysis. Gastroenterology 1982; 82:968.

- de Dombal FT, Clarke JR, Clamp SE, et al. Prognostic factors in upper G.I. bleeding. Endoscopy 1986; 18 Suppl 2:6.

- Graham DY, Smith JL. The course of patients after variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology 1981; 80:800.

- Grace ND. Prevention of initial variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1992; 21:149.

- Pasha MB, Hashir MM, Pasha AK, Pasha MB, Raza AA, Fatima M. Frequency of esophageal varices in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

https://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/bleeding-varices#2