BACKGROUND

The term “hepatitis” is used to describe a common form of liver injury. Hepatitis simply means “inflammation of the liver” (the suffix “itis” means inflammation and “hepa” means liver).

Hepatitis B is a specific type of hepatitis that is caused by a virus.

Fortunately, several medications are available for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B, and hepatitis B infection can be prevented by vaccination. Hepatitis B vaccines are safe and highly effective in preventing hepatitis B infection and are now given routinely to newborns and children in the in many countries.

DISEASE OCCURRENCE IN POPULATION

It is estimated that approximately two billion people worldwide have evidence of past or present infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV), and 248 million individuals are chronic carriers (i.e. positive for hepatitis B surface antigen [HBsAg]).

Pakistan is highly endemic with HBV with nine million people infected with HBV and its infection rate is on a steady rise.

RISK FACTORS

There are several ways to become infected with hepatitis B virus.

Contaminated needles:

Using contaminated needles can spread the hepatitis B virus. This includes tattooing, acupuncture, and ear piercing (if these procedures are performed with contaminated instruments). Sharing needles or syringes can also spread the virus.

Sex:

Sexual contact with someone who is infected is one of the most common ways to become infected with hepatitis B. If you are infected with hepatitis B, make sure your spouse or sex partner gets vaccinated.

Mother to infant:

Hepatitis B can be passed from a mother to her baby during or shortly after delivery. Having a Cesarean delivery (also called a C-section) does not prevent the virus from spreading. Experts believe that breastfeeding is safe.

To help prevent transmission from mother to infant, all pregnant women should have a blood test for a marker of hepatitis B virus, called hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). Normally, the HBsAg should be negative. If the mother is HBsAg-positive, she should be referred to a specialist.

Close contact:

Hepatitis B can be spread through close personal contact. This could happen if blood or other bodily fluids get into tiny cracks or breaks in your skin or in your mouth or eyes. The virus can live for a long time away from the body, meaning that it can be spread by sharing household items like toys, toothbrushes, or razors.

Blood transfusion and organ transplantation:

Nowadays, it is extremely rare for hepatitis B to be spread through blood transfusion or organ transplantation. Blood and organ donors are carefully screened for markers of hepatitis infection.

In the hospital:

In the hospital, hepatitis B virus can spread from one patient to another or from a patient to a doctor or nurse if there is an accidental needle stick. It is rare for a doctor/nurse to pass hepatitis B to a patient. Wearing gloves, eye protection, a face mask, and washing hands can help to prevent spreading the virus.

SIGN AND SYMPTOMS

Symptoms due to hepatitis B vary. After a person is first infected with hepatitis B, they can develop a flu-like illness that includes fever, abdominal pain, fatigue, decreased appetite, nausea, and in some cases yellowing of the skin and eyes (jaundice).

In the most severe cases, liver failure can develop, which is characterized by jaundice, fluid accumulation (swelling in the legs or abdomen), and confusion.

However, many patients do not develop symptoms, particularly if the infection occurs in infants and children. Not having symptoms does not necessarily mean that the infection is under control.

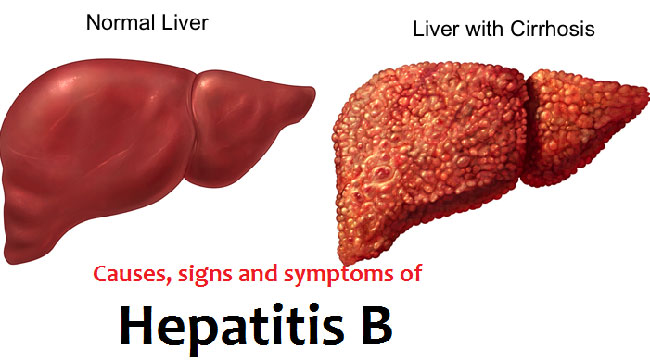

Most people with chronic hepatitis B have no symptoms until their liver disease is at a late stage. The most common early symptom is feeling tired. Everyone with chronic hepatitis B is at increased risk of developing complications, including liver scarring (called cirrhosis when the scarring is severe) and liver cancer.

Acute hepatitis B:

After a person is first infected with hepatitis B, they are said to have acute hepatitis. Most people with acute hepatitis B recover uneventfully.

However, in about 5 percent of adults (1 in 20) the virus makes itself at home in the liver, where it continues to make copies of itself for many years. People who continue to harbor the virus are referred to as “carriers”. If liver damage develops because of longstanding infection, the person is said to have chronic hepatitis.

Chronic hepatitis B:

Chronic hepatitis B develops more commonly in people who are infected with the virus at an early age (often at birth). Unfortunately, this is common in some parts of the world such as in Southeast Asia, China, and sub-Saharan Africa, where as many as 1 in 10 people have chronic hepatitis B infection.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

There are a number of tests that can be used to diagnose or monitor hepatitis B infection. Most of these tests are blood tests and include those that detect:

Hepatitis B surface antigen (abbreviated HBsAg):

HBsAg is a protein on the surface of the hepatitis B virus. This protein shows up in the blood 1 to 10 weeks after exposure to the hepatitis B virus and before a person starts to show symptoms of the infection. In people who recover, this protein usually disappears after 4 to 6 months. Its continued presence suggests that chronic infection has developed.

Hepatitis B surface antibody (abbreviated anti-HBs):

Anti-HBs helps the body’s immune system attack the hepatitis B virus. This protein is usually present in people who have recovered or who have been vaccinated against hepatitis B. People with this protein are usually immune to hepatitis B.

Hepatitis B core antibody (abbreviated anti-HBc):

Anti-HBc is usually present throughout the course of infection and stays in the blood after recovery. It is not present in people who have been vaccinated against hepatitis B.

Hepatitis B e antigen (abbreviated HBeAg):

HBeAg is a protein whose presence indicates that the hepatitis B virus is continuing to make copies of itself (replicating). Its presence usually indicates a high level of circulating virus and a high chance of transmission of infection.

Hepatitis B e antibody (abbreviated anti-HBe):

Anti-HBe usually signifies that virus replication has slowed down, but in some variants of hepatitis B, the virus continues to replicate at a rapid rate, and high levels of virus can be found in the circulation.

Hepatitis B DNA (abbreviated HBV DNA):

HBV DNA is the genetic material found in the hepatitis B virus. HBV DNA usually disappears from the blood after a person recovers. HBV DNA (viral load) is a measure of the concentration of virus in the circulating blood. Doctors use the levels of HBV DNA to decide who is a candidate for treatment with antiviral medicines and to track how well treatment is working.

Other tests:

There are many other tests that can reflect the health of the liver, but are not specific for hepatitis B. These include liver enzyme tests (alanine aminotransferase [ALT] and aspartate aminotransferase [AST]), bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, albumin, prothrombin time, and platelet count. As an example, an abnormally high ALT in the blood can be due to liver damage. Although liver damage can be caused by a virus (such as hepatitis B virus), it can also be caused by alcohol, drugs, fat accumulation in the liver (“fatty liver”), or other diseases.

A liver biopsy (in which a needle is inserted into the liver to remove a small piece of tissue for testing) is not routinely needed to diagnose hepatitis B virus infection. A liver biopsy is used to monitor liver damage in people with chronic hepatitis, help decide if treatment is needed, and find signs of cirrhosis or liver cancer.

The severity of liver disease or degree of liver damage can also be determined by other methods, without the need for liver biopsy. This may involve blood tests or tests to measure liver stiffness. In general, these tests are accurate in being able to tell early fibrosis (scarring) from advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis (when the scar tissue is severe). However, they cannot determine specific stages of fibrosis or determine the degree of inflammation.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Specific treatment for acute hepatitis B is usually not needed since in about 95 percent of adults, the immune system controls the infection and gets rid of the virus within about six months.

In people who develop chronic hepatitis, an antiviral medication might be recommended to reduce or reverse liver damage and to prevent long-term complications of hepatitis B. However, not all people with hepatitis B need immediate treatment. If you do not need to start treatment immediately, you will be monitored over time to know when hepatitis becomes more active (at that point you may begin antiviral treatment).

Once you start treatment, you will have regular blood tests to see how well the treatment is working and to detect side effects or drug resistance. Monitoring will continue after finishing treatment to determine if the infection has come back. Treatment should not be stopped without discussing this with your doctor because, in some cases, the virus can come back quickly, causing severe liver injury.

Antiviral medications

If your doctor thinks you should be treated, there are two types of antiviral medications that can be used, nucleos(t)ide analogues (these are oral medications that you take daily) and interferon (an injectable medication). Most patients receive an oral medication; however, your doctor will discuss these choices with you.

Nucleos(t)ide analogues:

Nucleos(t)ide analogues are oral medications that can be used to treat hepatitis B. Most patients will need long-term treatment to maintain control of the hepatitis B virus. For some patients, lifelong therapy is needed. Entecavir and tenofovir are the most commonly used oral agents. These antiviral medications are more potent and are less likely to cause the virus to develop resistance compared with other nucleos(t)ide analogues, such as lamivudine, adefovir, and telbivudine.

Entecavir:

Entecavir is a recommended treatment for patients who have not been treated with oral antivirals before. Although resistance to entecavir is uncommon in people who have never received antiviral therapy, it can occur in up to 50 percent of people who have used lamivudine for treatment of hepatitis B.

Tenofovir:

Tenofovir is a recommended treatment for both patients who have been and those who have never been treated with oral antivirals for hepatitis B. Tenofovir is available in two formulations: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and tenofovir alafenamide. For most patients, tenofovir alafenamide is preferred, if it is available.

Tenofovir is effective in suppressing hepatitis B virus that is resistant to other antiviral agents, such as lamivudine, telbivudine, or entecavir. It is also effective when used to treat patients who have a form of the virus that is resistant to adefovir; however, there may be a slower decline in hepatitis B virus levels when certain adefovir resistance mutations are present. Resistance to tenofovir has not been reported.

Other agents:

Several nucleos(t)ide medications are no longer recommended for the treatment of chronic HBV in most countries. These include:

- Lamivudine:

Lamivudine is effective in decreasing hepatitis B virus activity and ongoing liver inflammation. It is safe in patients with liver failure, and long-term treatment can decrease the risk of liver failure and liver cancer. However, a resistant form of hepatitis B virus (referred to as a “YMDD mutant”) frequently develops in people who take lamivudine long term.

- Telbivudine:

Telbivudine is more potent than lamivudine and adefovir. However, resistance to telbivudine is common, and hepatitis B virus that is resistant to lamivudine is also resistant to telbivudine.

- Adefovir:

Adefovir is another oral medication for people who have detectable hepatitis B virus activity and ongoing liver inflammation. Adefovir is a weak antiviral medicine and resistance is more common than with entecavir or tenofovir.

Interferon-alfa:

Interferon-alfa is an appropriate treatment for people with chronic hepatitis B infection who have detectable virus activity, ongoing liver inflammation, and no cirrhosis. Interferon-alfa may be considered in young patients who do not have advanced liver disease and do not wish to be on long-term treatment. Interferon-alfa is not appropriate for people with cirrhosis who have liver failure or for people who have a recurrence of hepatitis after liver transplantation.

Interferon is given for a finite duration. Pegylated interferon, a long acting interferon taken once a week, is given for one year. This is in contrast to the other hepatitis treatments, which are given by mouth for many years until a desired response is achieved. Drug resistance to interferon has not been reported.

The disadvantages of interferon-alfa are that it must be taken by injection and it can cause many side effects.

Liver transplantation:

Liver transplantation may be the only option for people who have developed advanced cirrhosis. The liver transplantation process is elaborate, involving an extensive screening process to ensure that a person is a good candidate. Thus, not all patients with cirrhosis are eligible, and only those with the most advanced cirrhosis or early stage liver cancer and otherwise good medical and social conditions will be put on the transplant waiting list. Because of the shortage of donors, not all patients on the transplant waiting list will receive a liver transplant.

PRECAUTIONS

Vaccinations:

Everyone with chronic hepatitis B should be vaccinated against hepatitis A unless they are known to be immune. Influenza vaccination is recommended once per year, usually in the fall. Patients with liver disease should also receive standard immunizations, including a diphtheria and tetanus booster, every ten years.

Liver cancer screening:

Regular screening for liver cancer is also recommended, particularly for older individuals, those with cirrhosis, and patients with a family history of liver cancer. In general, this includes an ultrasound examination of the liver every six months.

Diet:

No specific diet has been shown to improve the outcome in people with hepatitis B. The best advice is to eat a normal healthy and balanced diet and to maintain a normal weight.

Alcohol:

Alcohol should be avoided since it can worsen liver damage. All types of alcoholic beverages can be harmful to the liver. People with hepatitis B can develop liver complications even with small amounts of alcohol.

Prescription and nonprescription drugs:

Many medications are broken down by the liver. Thus, it is always best to check with a healthcare provider or pharmacist before starting a new medication. As a general rule, unless the liver is already scarred, most drugs are safe for people with hepatitis B.

An important possible exception is acetaminophen; the maximum recommended dose in people with liver disease is no more than 2 grams (2000 mg or four extra strength tabs or capsules) in 24 hours. Most acetaminophen tabs or capsules contain 325 or 500 mg. Many over-the-counter cold and headache medicines under different names may contain acetaminophen.

You should avoid ibuprofen, naproxen, and aspirin if you have cirrhosis.

Herbal medications:

No herbal treatment has been proven to improve outcomes in patients with hepatitis B, and some can cause serious liver toxicity. Herbal treatments are not recommended for anyone with hepatitis B.

Exercise:

Exercise is good for overall health and is encouraged, but it has no effect on the hepatitis B virus. Exercise is not harmful to the liver, even in people with chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis.

Preventing infection of close contacts:

Acute and chronic hepatitis B are contagious. Thus, people with hepatitis B should discuss measures to reduce the risk of infecting close contacts. This includes the following:

- Discuss the infection with any sexual partners and use a latex condom with every sexual encounter.

- Do not share razors, toothbrushes, or anything that has blood on it.

- Cover open sores and cuts with a bandage.

- Do not donate blood, body organs, other tissues, or sperm.

- Immediate family and household members should be tested for hepatitis B. Anyone who is at risk of hepatitis B infection should be vaccinated.

- Do not share any injection drug equipment (needles, syringes).

- Clean blood spills with a mixture of 1 part household bleach to 9 parts water.

Hepatitis B cannot be spread by:

- Hugging or kissing

- Sharing eating utensils or cups

- Sneezing or coughing

- Breastfeeding

Preventing infection from mother to child:

If a mother tests positive for hepatitis B surface antigen, certain steps can be taken to decrease the risk of transmitting the virus to the infant. These include:

- Antiviral medications may be recommended for the mother if the amount of virus in her blood (viral load) is high. These medications are used to decrease the viral load.

- Infants should be given a shot soon after birth called hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG). HBIG provides immediate protection to the infant, but the effect only lasts a few months.

- Infants should also receive the hepatitis B vaccine series. The first dose of hepatitis B vaccine should be given at birth. Two other doses can be administered along with their regular childhood immunizations at approximately 1 and 6 months of age. Finishing all three doses is important for long-term protection.

These infants should have a blood test for hepatitis B surface antigen and for hepatitis B antibody at 9 to 12 months of age, or one to two months after the last dose of hepatitis B vaccine if immunization is delayed. If the hepatitis B surface antibody test is negative, additional vaccination is needed.

REFERENCES

Ott JJ, Stevens GA, Groeger J, Wiersma ST.

Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection:

new estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine 2012; 30:2212.

Schweitzer A, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT, et al.

Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection:

a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet 2015; 386:1546.

Noorali S, Hakim ST, McLean D, Kazmi SU, Bagasra O.

Prevalence of Hepatitis B virus genotype D in females in Karachi, Pakistan.

J Infect Developing Countries. 2008;2:373–378.

Hakim ST, Kazmi SU, Bagasra O.

Seroprevalence of Hepatitis B and C Genotypes Among Young Apparently Healthy Females of Karachi-Pakistan.

Libyan J Med. 2008;3:66–70. doi: 10.4176/071123

Hepatitis prevention & control program Sindh (chief minister's initiative) 2009.

directorate general health services, Hyderabad, Sindh, Pakistan