BACKGROUND

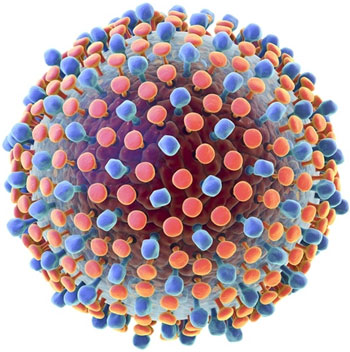

Hepatitis C is a liver disease caused by the hepatitis C virus – the virus can cause both acute and chronic hepatitis infection, ranging in severity from a mild illness lasting a few weeks to a serious, lifelong illness.

The hepatitis C virus is a bloodborne virus and the most common modes of infection are through unsafe injection practices; inadequate sterilization of medical equipment; and the transfusion of unscreened blood and blood products.

DISEASE OCCURRENCE IN POPULATION

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is one of the most common chronic liver disease and accounts for 8000 to 13,000 deaths each year. Globally, it was estimated that in 2005, more than 185 million people had hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibodies (prevalence of 2.8 percent).

HCV is highly endemic in Pakistan, where a national survey, conducted in 2007–2008, estimated HCV prevalence at 4.8%. In Pakistan 10 million people are presumed to be infected with HCV.

RISK FACTORS

Many people with hepatitis C infection do now know how they were infected. The hepatitis C virus is spread by contact with blood. The most common ways people have gotten infected are:

- Sharing needles, syringes, or other paraphernalia used for injection drug use

- Receiving a blood transfusion before 1990, when blood was not routinely tested for hepatitis C or other infections

- Having sex with an infected person

It is also possible to get the hepatitis C virus by:

- Getting body piercings or tattoos done with improperly sanitized equipment

- Sharing cocaine straws

- Sharing toothbrushes, razors, or other things that could have blood on them

- Getting stuck with a sharp object that has contaminated blood on it (as might happen in a healthcare setting)

Pregnant women can rarely spread the virus to their fetus.

There is no evidence that any of the following activities lead to transmission of hepatitis C:

- Kissing or hugging

- Sneezing or coughing

- Casual contact or other contact that does not involve blood

- Sharing food, water, eating utensils, or drinking glasses

SIGN AND SYMPTOMS

Long-term infection with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) is known as chronic hepatitis C. Chronic hepatitis C is usually a “silent” infection for many years, until the virus damages the liver enough to cause the signs and symptoms of liver disease. Among these signs and symptoms are:

- Bleeding easily

- Bruising easily

- Fatigue

- Poor appetite

- Yellow discoloration of the skin and eyes (jaundice)

- Dark-colored urine

- Itchy skin

- Fluid buildup in your abdomen (ascites)

- Swelling in your legs

- Weight loss

- Confusion, drowsiness and slurred speech (hepatic encephalopathy)

- Spider-like blood vessels on your skin (spider angiomas)

Every chronic hepatitis C infection starts with an acute phase. Acute hepatitis C usually goes undiagnosed because it rarely causes symptoms. When signs and symptoms are present, they may include jaundice, along with fatigue, nausea, fever and muscle aches. Acute symptoms appear one to three months after exposure to the virus and last two weeks to three months.

Acute hepatitis C infection doesn’t always become chronic. Some people clear HCV from their bodies after the acute phase, an outcome known as spontaneous viral clearance.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

Healthcare providers diagnose hepatitis C using two types of test. One type of test checks the blood for antibodies – proteins made by the immune system in response to the virus. The other type of test checks for a substance called RNA made by the virus itself. Most people who have a negative antibody test do not have hepatitis C infection and do not need additional testing. However, healthcare providers may also order an RNA test if they suspect acute infection or if the person being tested has a potentially compromised immune system (such as those with HIV infection). People who have an active chronic infection will have both a positive antibody test and a positive RNA test. People who have a positive antibody test and a negative RNA test either had a false positive antibody test or had the infection at one time but were able to fight it off.

Home testing: Hepatitis C antibody test kit can be bought without a prescription and use at home. To take the test, you collect your own sample of blood and send it to a lab, which will return the results in 4 to 10 business days.

Determining the virus genotype: Once a diagnosis of hepatitis C is made, it’s important to identify the variant of the virus a person has. There are several forms of the virus—called genotypes—each of which must be treated differently. In the Pakistan, genotype 3 is the most common, followed by genotype 1.

Assessing the degree of liver damage: Another important aspect of hepatitis C diagnosis is to determine the condition of the liver at the time of diagnosis. Healthcare providers can assess the degree of liver damage using a number of blood tests, an imaging test called ultrasound-based transient elastography (which is not available everywhere), or, rarely, a liver biopsy.

Checking for other infections: People who have hepatitis C are at risk for infection with HIV and hepatitis B, in part because these infections can be transmitted in the same way as hepatitis C. They are also more vulnerable to any infection that targets the liver. As a result, after diagnosing hepatitis C, healthcare providers often do follow-up tests for HIV, and hepatitis A and B. People whose tests show they are not immune to hepatitis A and B should get vaccinated against these infections.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

There are a number of medications to treat hepatitis C. In the vast majority of people, these medications have an excellent chance of curing the infection.

Decision to treat: People diagnosed with hepatitis C must decide – in conjunction with their healthcare providers – whether and when to treat their infection. In general, treatment is safe and effective, and anyone with hepatitis C should consider getting treatment. Factors that go into making treatment decisions include the condition of the person’s liver, the person’s overall health, and the genotype the person has. Other factors to consider include whether the person has other illnesses, such as kidney disease, and whether the person already had a liver transplant. Antiviral medications should not be started during pregnancy as their safety in this setting has not yet been evaluated.

Treatment regimens: People who do undergo treatment use one or more medications for several months. The specific combination of agents and the duration of treatment are determined based on the genotype involved and the person’s individual characteristics.

- Sofosbuvir: is indicated for treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection genotypes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 as part of a combination antiviral regimen.

- Daclatasvir: is indicated for use with sofosbuvir for treatment of chronic HCV genotype 3 infections.

- Sofosbuvir-velpatasvir: Velpatasvir and sofosbuvir are coformulated in a single tablet. It is pan-genotypic (for all genotypes 1-6).

- Sofosbuvir-velpatasvir-voxilaprevir: This regimen is pan-genotypic (for all genotypes) and mainly reserved for patients who have prior failure on Direct Acting Antiviral (DAA).

- Ledipasvir/sofosbuvir: This regimen is administered with or without weight-based ribavirin, depending on the patient population. It is indicated for chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection and genotypes 4, 5, and 6 infection in adults.

- Interferons- It is no more used in clinical practice. There are two formulation available:

- PEG-IFN alfa-2a

- PEG-IFN alfa-2b

- Ribavirin: is an antiviral drug. Given alone, ribavirin has little effect on the course of hepatitis C. Given with interferon / DAAs, it significantly augments the rate of sustained virologic response.

Side effects caused by hepatitis C medications: People being treated for hepatitis C sometimes develop medication side effects, although most are not serious. If you are being treated for hepatitis C, you should call your healthcare provider any time you develop a side effect that bothers you. Some of the medications used to treat hepatitis can make you tired, nauseated, or have headaches.

In very rare cases, people need to stop taking their medications because of side effects. But DO NOT STOP TAKING YOUR MEDICATIONS because of side effects until you speak with your healthcare provider. Only he or she can tell if you need to stop the medications. Besides, your healthcare provider might have a way to deal with the side effects so that you can keep taking the medications. For example, if you feel sick to your stomach, your healthcare provider might give you a medication to help with this. If you have anemia, your healthcare provider might lower the dose you take of the medication causing the problem. There are often ways to deal with side effects so that you are comfortable enough to keep taking your medications.

Even if your healthcare provider can’t make your side effects go away completely, remember that you only need to take these medications for a while. If you put up with some side effects, there is a good chance you will be cured.

PRECAUTIONS

Never share needles: Intravenous drug users are at greatest risk of becoming infected with hepatitis C because many share needles. In addition to needles, the virus may be present in other equipment used with illicit drugs. Even sharing a straw or dollar bill when snorting cocaine could lead to hepatitis C transmission. Bleeding in the nasal passages frequently occurs when taking cocaine this way, and microscopic droplets may enter the straw and be passed on to the next user, even if they can’t be seen.

Avoid direct exposure to blood or blood products: If you are a medical worker or health care provider, take precautionary measures to avoid coming into direct contact with blood. Any tools that draw blood in the workplace should be discarded safely or sterilized appropriately to prevent hepatitis C infection.

Don’t share personal care items: Many items that we use on a daily basis will occasionally be exposed to blood. Often people will cut themselves while shaving, or their gums will bleed while brushing their teeth. Even small amounts of blood can potentially infect someone, so it is important not to share items such as toothbrushes, razors, nail and hair clippers, and scissors. If you are already infected with hepatitis C, make sure you keep your personal items, such as razors and toothbrushes, separate and out of reach from children.

Choose tattoo and piercing parlors carefully: Only use a licensed tattoo and piercing artist who follows appropriate sanitary procedures. A new, disposable needle and ink well should be used for each customer. If in doubt, inquire about their disposable products and sanitary procedures before getting a tattoo or piercing.

Practice safe sex: It is rare for hepatitis C to be transmitted through sexual intercourse, but there is greater risk of getting hepatitis C if you have a sexually transmitted disease, HIV, or multiple sex partners or if you engage in rough sex.

Avoid alcohol: Because of the association with more rapid progression of liver disease, avoid alcohol.

REFERENCES

Mohd Hanafiah K, Groeger J, Flaxman AD, Wiersma ST.

Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection:

new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology 2013; 57:1333.

Qureshi H, Bile KM, Jooma R, Alam SE, Afridi HUR.

2010 Prevalence of hepatitis B and C viral infections in Pakistan:

findings of a national survey appealing for effective prevention and control measures. East Mediterr. Health J. 16, S15–S23

Hamid S et al. J Pak Med Assoc 2004; 54: 146-150

Holmberg S. CDC Yellow Book:

Infectious Diseases Related to Travel. 2011.

Kabir ahmed the lancet Report:

Pakistan a cirrhotic State? 2004

Spradling PR, Rupp L, Moorman AC, et al.

Hepatitis B and C virus infection among 1.2 million persons with access to care:

factors associated with testing and infection prevalence. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:1047.

Everson GT, Weinberg H. Living With Hepatitis C: A Survivor's Guide.

3rd ed. Long Island City, New York:

Hatherleigh Health; 2002.