EPIDEMIOLOGY

Cirrhosis affects 3.6 out of every 1000 adults in North America, and is responsible for more than one million days of work-loss and 32,000 deaths annually. A major cause of cirrhosis-related morbidity and mortality is the development of variceal hemorrhage, a direct consequence of portal hypertension.(1) Each episode of active variceal hemorrhage is associated with 30 percent mortality.(2,3) In addition, survivors of an episode of active bleeding have a 70 percent risk of recurrent hemorrhage within one year of the bleeding episode.(4)

Variceal hemorrhage occurs in 25 to 40 percent of patients with cirrhosis.(5) While several modalities are available for primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding, many are associated with significant adverse effects.

According to one study conducted in Pakistan, esophageal varices (53%) have been found the major cause of bleeding followed by duodenal ulcer (12%) and gastric ulcer (14%).(6)

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY(7)

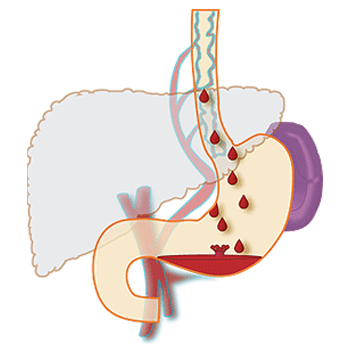

Formation of varices:

Portal pressure is determined by the product of portal flow volume and resistance to outflow from the portal vein. Portal hypertension (defined as hydrostatic pressure >5 mmHg) results initially from obstruction to portal venous outflow. Obstruction may occur at a presinusoidal (portal vein thrombosis, portal fibrosis, or infiltrative lesions), sinusoidal (cirrhosis), or postsinusoidal (veno-occlusive disease, Budd-Chiari syndrome) level. Cirrhosis is the most common cause of portal hypertension; in these patients, elevated portal pressure results from both increased resistance to outflow through distorted hepatic sinusoids, and enhanced portal inflow due to splanchnic arteriolar vasodilation.

Varices develop in order to decompress the hypertensive portal vein and return blood to the systemic circulation. They are seen when the pressure gradient between the portal and hepatic veins rises above 12 mmHg; patients with lower values do not form varices and do not bleed. The portal-hepatic venous pressure gradient is obtained by hepatic venous catheterization, with measurement of the difference between the wedged hepatic venous pressure (which approximates the sinusoidal and portal pressures in cirrhosis) and the free hepatic venous pressure. Although it does not predict the size of varices, it may be useful for monitoring the success of therapy aimed at lowering portal pressures, such as beta blockers.

Predictive factors:

Numerous clinical and physiologic factors are useful in predicting the risk of variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. These include:

- Location of varices

- Size of varices

- Appearance of varice

- Clinical features of the patient

- Variceal pressure

Location of varices: The most common sites for development of varices are the distal esophagus, stomach, and rectum, although theoretically varices may develop at any level of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract between the esophagus and rectum. Varices develop deep within the submucosa in the mid-esophagus, but become progressively more superficial in the distal esophagus. Thus, esophageal varices at the gastroesophageal junction have the thinnest layer of supporting tissue and are most likely to rupture and bleed.

Size of varices: The risk of variceal bleeding correlates independently with the diameter (size) of the varix. The explanation for the relationship between variceal size and bleeding risk is derived from Laplace’s law; small increases in the vessel radius result in a large increase in wall tension (which is the force tending to cause variceal rupture).

There are several ways in which esophageal variceal size is quantified; none are exact and all involve subjective evaluation. A commonly employed system of classification includes the following:(8,9)

- F1: Small, straight varices

- F2: Enlarged, tortuous varices that occupy less than one-third of the lumen

- F3: Large, coil-shaped varices that occupy more than one-third of the lumen

Appearance of varices: In addition to size, several morphologic features of varices observed at endoscopy have been correlated with an increased risk of hemorrhage. These features include a number relating to a red appearance, or “red signs”:

- Red wale marks are longitudinal red streaks on varices that resemble red corduroy wales

- Cherry red spots are discrete red cherry-colored spots that are flat and overlie varices

- Hematocystic spots are raised discrete red spots overlying varices that resemble “blood blisters”

Diffuse erythema denotes a diffuse red color of the varix

NATURAL HISTORY(10)

There are two distinct phases in the course of variceal hemorrhage: an acute phase and a later phase in which there is a high risk of recurrent bleeding. The acute phase starts with the onset of active hemorrhage. Only 50 percent of patients with variceal hemorrhage stop bleeding spontaneously; this is quite different from the more than 90 percent spontaneous cessation rate in patients with other forms of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Patients with Child class C cirrhosis and large, actively spurting varices are less likely to achieve spontaneous hemostasis. In addition, a hepatic venous pressure gradient >20 mmHg is associated with a greater risk of continued or recurrent bleeding. Active infection is associated with an increased risk of bleeding and multiorgan failure, which forms the basis for the recommended use of antibiotics in patients with variceal bleeding.

Following cessation of active hemorrhage, there is a period of approximately six weeks in which there is a high risk of recurrent hemorrhage. The greatest risk is within the first 48 to 72 hours, and over 50 percent of all early rebleeding episodes occur within the first 10 days. Risk factors for early rebleeding include age greater than 60 years, renal failure, large varices, and severe initial bleeding as defined by a hemoglobin below 8 g/dL at admission.

The risk of bleeding and of death in patients who survive six weeks is similar to that in patients with cirrhosis of equivalent severity who have never bled. One-year survival in those who survive two weeks after a variceal bleed is approximately 52 percent. Survival appears to have increased since the 1980s due to a decrease in short-term mortality. Acute bleeding from varices is associated with approximately 15 to 20 percent 30-day mortality.

SIGN AND SYMPTOMS

Esophageal varices usually don’t cause signs and symptoms unless they bleed. Signs and symptoms of bleeding esophageal varices include:

- Hematemesis

- Melena (black stools)

- Lightheadedness

- Jaundice

- Easy bleeding or bruising

- Ascites)

- Low blood pressure

- Rapid heart rate

- Shock (in severe cases)

- Stomach pain

Even after the bleeding has been stopped, there can be serious complications, such as pneumonia, sepsis, liver failure, kidney failure, confusion, and coma.

RATIONALE FOR SCREENING

The practice guideline from the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) and the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) for gastroesophageal varices suggests that all patients with hepatic cirrhosis should be screened for varices at least every other year.(11) Of those screened following a diagnosis of cirrhosis, approximately 50% will have gastroesophageal varices and roughly one third will have varices sufficiently large to require prophylaxis.(12) Screening at endoscopy should determine the size of esophageal varices(11) because patients with varices ≥ 5 mm in diameter are at the greatest risk for bleeding and should receive prophylaxis. Red wales are also an indicator of bleeding risk. Even varices that are < 5 mm in diameter with red wales are more likely to bleed and should receive drug prophylaxis.

Endoscopy remains the best screening method for gastroesophageal varices in patients with known or suspected cirrhosis.(13) If initial screening endoscopy fails to identify varices, upper endoscopy should be repeated at 2 yearly intervals. For those with decompensated cirrhosis, more frequent screening endoscopy may be warranted. Wedged hepatic vein pressure measurement is the best predictor of varix development,(13) and those with pressures > 20 mm Hg have the highest risk for hemorrhage.(14)

Noninvasive techniques to look for significant portal hypertension or varices are of limited value.(15) Thrombocytopenia,(16) splenomegaly,(17) and liver function tests can all be abnormal in the absence of esophageal varices. Estimates of liver stiffness using tissue elastography assist in identifying cirrhosis but are limited in their ability to identify significant portal hypertension.(18) Capsule endoscopy with a dual camera capsule has been tested in patients who have had both capsule endoscopy and esophagogastroduodenoscopy on the same day.(19) The sensitivity was 76% and specificity 82% for esophageal varices with capsule endoscopy, as compared with conventional endoscopy. Computed tomography is 65%-100 % sensitive and 50%-100% specific for large esophageal varices.(20,21) Other noninvasive markers such as the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD), Child-Pugh score, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to platelet count index appear to lack sufficient sensitivity to screen for high-risk varices.(22)

Clinical factors associated with variceal hemorrhage have been studied in 240 patients with bleeding varices and compared with 240 nonbleeding patients matched for cirrhosis and degree of decompensation. Constipation, vomiting, severe coughing, and excessive ethanol consumption all were associated with the risk of variceal hemorrhage.(15)

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

Endoscopy is the criterion standard for evaluating esophageal varices and assessing the bleeding risk.(23-28) This procedure is performed by a surgeon or a gastroenterologist with the patient under light sedation. The procedure involves using a flexible endoscope inserted into the patient’s mouth and through the esophagus to inspect the mucosal surface.

When esophageal varices are discovered, they are graded according to their size, as follows:

- Grade 1 – Small, straight esophageal varices

- Grade 2 – Enlarged, tortuous esophageal varices occupying less than one third of the lumen

- Grade 3 – Large, coil-shaped esophageal varices occupying more than one third of the lumen

The esophageal varices are also inspected for red wheals, which are dilated intra-epithelial veins under tension and which carry a significant risk for bleeding. The grading of esophageal varices and identification of red wheals by endoscopy predict a patient’s bleeding risk, on which treatment is based.

CT scanning and MRI are identical in their usefulness in diagnosing and evaluating the extent of esophageal varices. These modalities have an advantage over endoscopy because CT scanning and MRI can help in evaluating the surrounding anatomic structures, both above and below the diaphragm. CT scanning and MRI are also valuable in evaluating the liver and the entire portal circulation.

These modalities are used in preparation for a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure or liver transplantation and in evaluating for a specific etiology of esophageal varices. These modalities also have an advantage over both endoscopy and angiography because they are noninvasive. CT scanning and MRI do not have strict criteria for evaluating the bleeding risk, and they are not as sensitive or specific as endoscopy. CT scanning and MRI may be used as alternative methods in making the diagnosis if endoscopy is contraindicated (e.g. in patients with a recent myocardial infarction or any contraindication to sedation).

In the past, angiography was considered the criterion standard for evaluation of the portal venous system. However, current CT scanning and MRI procedures have become equally sensitive and specific in the detection of esophageal varices and other abnormalities of the portal venous system. Although the surrounding anatomy cannot be evaluated the way they can be with CT scanning or MRI, angiography is advantageous because its use may be therapeutic as well as diagnostic. In addition, angiography may be performed if CT scanning or MRI findings are inconclusive.(29)

Ultrasonography, excluding EUS, and nuclear medicine studies are of minor significance in the evaluation of esophageal varices.

TREATMENT OPTIONS(30)

Primary Prophylaxis

For patients with medium-to-large esophageal varices (> 5 mm in diameter), nonselective beta-blocker prophylaxis will reduce the risk for bleeding.(13) Although beta-blocker therapy will not prevent varices from forming, it can reduce the likelihood of gastrointestinal hemorrhage by 40% through a reduction of portal pressure flow from reduced splanchnic arterial vasodilation and cardiac output. Nonselective beta-blockers such as propranolol, nadolol, or carvedilol should be used. Side effects including fatigue, dyspnea, lightheadedness, and bradycardia can develop. Carvedilol has been directly compared with band ligation, and achieved a lower rate of first bleed. No difference in bleeding-related or overall mortality was observed. The goal of beta-blocker therapy is a reduction of pulse rate by 25% or a rate of 55 beats per minute. Potential contraindications to beta-blocker therapy include asthma, heart block, obstructive pulmonary disease, aortic outflow tract disorders, or resulting severe side effects. Beta-blocker therapy should be continued indefinitely because the risk for bleeding is increased when the drug is stopped. Up to one third of patients may not achieve sufficient reduction of portal pressure to prevent bleeding. Varices < 5 mm in diameter with red wale signs in patients with decompensated cirrhosis may also benefit from beta-blocker therapy. Addition of isosorbide has been studied, but the data are insufficient to recommend its use with beta-blockers.(13)

Band ligation of esophageal varices at upper endoscopy for moderate-to-large esophageal varices will also reduce the likelihood of first bleeding.(13) Meta-analyses suggest that banding is either more effective or equally effective)as beta-blockers. Although banding has a reduced daily side effect profile when compared with beta-blockers, some complications can be severe, including bleeding from superficial ulceration or esophageal perforation. For that reason, initial therapy should be with beta-blockers reserving primary use of band ligation for those with contraindications or intolerance to beta-blockers. The simultaneous use of band ligation and beta-blockers for primary prophylaxis is unnecessary.

Gastric varices tend to have a lower risk for bleeding than esophageal varices, although bleeding can be more severe. Varices in the fundus of the stomach are more likely to bleed then varices at other gastric locations. Beta-blocker therapy should be used as primary prophylaxis for gastric varices. Intravariceal injection of glue (cyanoacrylate) as primary prophylaxis does not lead to a greater reduction of subsequent mortality than beta-blockers.

Sclerotherapy of esophageal varices is not recommended for primary prophylaxis due to the frequency of associated complications. Surgical shunts or TIPS are not recommended due to operative mortality and/or the development of postprocedure hepatic encephalopathy.

Acute variceal hemorrhage

Patients who develop variceal hemorrhage should be transfused to maintain systemic blood pressure at 100 mm Hg and hemoglobin at ≥ 8 gm/dL. Patients with coronary artery disease may need transfusion to higher hemoglobin levels. It is important to not over transfuse. The patient’s airway should be controlled as necessary and antibiotics administered. Antibiotics can reduce the risk for systemic infection, renal failure, rebleeding, and death. Octreotide, a somatostatin analogue, is administered as soon as suspected variceal hemorrhage is identified. This off-label use of octreotide has an uncertain mechanism of action but appears effective in reducing or stopping variceal bleeding. Once initiated, octreotide should be maintained for 2 to 5 days.(13) Vasopressin, a posterior pituitary hormone, is a potent vasoconstrictor that will also reduce portal pressure. It also increases systemic vasoconstriction and has been associated with myocardial infarction and small bowel necrosis. Terlipressin, a long-acting analogue of vasopressin, can reduce mortality from variceal hemorrhage.

Balloon tamponade with a Linton-Nachlas or Sengstaken-Blakemore tube can be a bridge to endoscopic therapy in massive variceal hemorrhage. Care should be taken to prevent insufflation of the gastric balloon within the esophagus and an immediate radiograph centered on the xiphoid should be obtained to ensure that placement is correct. Balloon tamponade is 90% effective in stopping bleeding, although about one half of patients will relapse with bleeding when the balloon is released in 24 to 72 hours.

Urgent endoscopy should typically be completed within 12 hours of bleeding. Band ligation is preferred for control of bleeding and is considered the treatment of choice.(13) Side effects include initial dysphagia, esophageal ulceration, and esophageal perforation (rare). Risk for banding-induced ulceration can be reduced by addition of a proton-pump inhibitor. Banding should be repeated until obliteration of varices is complete. Addition of a beta-blocker is useful in secondary prophylaxis. Sclerotherapy of esophageal varices is inferior to band ligation.

Uncontrolled bleeding, defined as continued bleeding at 24 hours, is uncommon when band ligation and octreotide are used.(13) If bleeding continues, repeat banding or placement of TIPS, or surgical shunting should be considered. TIPS placement involves creating an intrahepatic shunt between the portal vein and hepatic vein using a covered stent. This is effectively a side-to-side portosystemic shunt, and, although rebleeding rates are low, hepatic encephalopathy is frequent. Progressive occlusion of the shunt can develop, and hepatic ultrasound should be repeated every 4-6 months to ensure patency.

Gastric varices may be associated with severe bleeding. Gastric banding is associated with significant rebleeding due to gastric ulceration when the band sloughs. The use of detachable snares may be more effective, and is under study. Often, bleeding patients with uncontrolled gastric varices are treated with a surgical shunt or TIPS. Intravariceal injection of polymer (N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate) can occlude gastric varices.(13) Off-label use of 2-octyl cyanoacrylate appears to be more effective than band ligation for gastric varices. Complete obliteration of gastric varices requires repetitive injections and can be supplemented with endoscopic ultrasound to ensure adequate treatment.

Secondary Prophylaxis Following Variceal Hemorrhage

The risk for rebleeding from esophageal varices after initial control is approximately 70% if no further treatment is provided. Overall mortality from rebleeding is 30% and is more frequent with large varices, initial severe hemorrhage, and decompensated liver disease. As noted, banding is more effective than sclerotherapy for long-term management of esophageal varices, especially when used in combination with beta-blocker therapy. For patients who have portal hypertensive gastropathy as a cause of initial gastrointestinal bleeding, long-term beta-blocker therapy should be provided.

GOAL OF THERAPY

There are three primary goals of management during the active bleeding episode: hemodynamic resuscitation, prevention and treatment of complications, and treatment of bleeding. All three need to be pursued simultaneously and often require the coordinated care of a hepatologist, critical care clinician, critical care nurse, surgeon, and interventional radiologist.

GUIDELINES

To view, “UK guidelines on the management of variceal haemorrhage in cirrhotic patients”, please click on below link:

http://gut.bmj.com/content/early/2015/05/12/gutjnl-2015-309262.full.pdf+html

To view, “Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: Report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: Stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension”, please click on below link:

http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0168827815003499/1-s2.0-S0168827815003499-main.pdf?_tid=89fa1c6a-ca5c-11e5-9300-00000aab0f6c&acdnat=1454493630_6d1238f74baebfa7460dd2f1bbdf237f

To view, “AASLD practice guidelines on Prevention and Management of Gastroesophageal Varices and Variceal Hemorrhage in Cirrhosis”, please click on below link:

https://www.aasld.org/sites/default/files/guideline_documents/GastroVaricesand2009Hemorrhage.pdf

To view, “World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines on Esophageal varices”, please click on below link:

http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/UserFiles/file/guidelines/esophageal-varices-english-2014.pdf

To view, “National Clinical Guideline Centre guidelines on Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding – Management”, please click on below link:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK247794/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK247794.pdf

PRECAUTIONS

Currently, no treatment can prevent the development of esophageal varices in people with cirrhosis. While beta blocker drugs are effective in preventing bleeding in many people who have esophageal varices, they do not prevent esophageal varices from forming.

Advice following preventions to patient:

- Don’t drink alcohol: People with liver disease are often advised to stop drinking alcohol, since the liver processes alcohol. Drinking alcohol may stress an already vulnerable liver.

- Eat a healthy diet: Choose a plant-based diet that’s full of fruits and vegetables. Select whole grains and lean sources of protein. Reduce the amount of fatty and fried foods you eat.

- Maintain a healthy weight: An excess amount of body fat can damage your liver. Obesity is associated with a greater risk of complications of cirrhosis. Lose weight if you are obese or overweight.

- Use chemicals sparingly and carefully: Follow the directions on household chemicals, such as cleaning supplies and insect sprays. If you work around chemicals, follow all safety precautions. Your liver removes toxins from your body, so give it a break by limiting the amount of toxins it must process.

- Reduce your risk of hepatitis: Sharing needles and having unprotected sex can increase your risk of hepatitis B and C. Protect yourself by abstaining from sex or using a condom if you choose to have sex. Ask your doctor whether you should be vaccinated for hepatitis B and hepatitis A.

REFERENCES

- Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J. Management of varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:823.

- Smith JL, Graham DY. Variceal hemorrhage: a critical evaluation of survival analysis. Gastroenterology 1982; 82:968.

- de Dombal FT, Clarke JR, Clamp SE, et al. Prognostic factors in upper G.I. bleeding. Endoscopy 1986; 18 Suppl 2:6.

- Graham DY, Smith JL. The course of patients after variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology 1981; 80:800.

- Grace ND. Prevention of initial variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1992; 21:149.

- Pasha MB, Hashir MM, Pasha AK, Pasha MB, Raza AA, Fatima M. Frequency of esophageal varices in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Arun J Sanyal. Prediction of variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. Uptodate. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/prediction-of-variceal-hemorrhage-in-patients-with-cirrhosis?search=variceal%20hemorrhage%20epidemiology&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1 (Accessed on 2019 Jan 30)

- North Italian Endoscopic Club for the Study and Treatment of Esophageal Varices. Prediction of the first variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and esophageal varices. A prospective multicenter study. N Engl J Med 1988; 319:983.

- Beppu K, Inokuchi K, Koyanagi N, et al. Prediction of variceal hemorrhage by esophageal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 1981; 27:213.

- Arun J Sanyal. General principles of the management of variceal hemorrhage. Uptodate: Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/general-principles-of-the-management-of-variceal-hemorrhage?search=BLEEDING%20ESOPHAGEAL%20VARICES&source=search_result&selectedTitle=2~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=2 (Accessed on 2019 Jan 30)

- Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey WD. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2086-2102.

- Cales P, Desmorat H, Vinel JP, et al. Gut. 1990;31:1298-1302.

- de Franchis R. Evolving consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno IV consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy and portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2005;43:167-176.

- Bosch J, Berzigotti A, Garcia-Pagan JC, Abraldes JG. The management of portal hypertension: rational basis, available treatments and future options. J Hepatol. 2008;48(supp 1):S68-S92.

- Thabut D, Moreau R, Lebrec D. Noninvasive assessment of portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2011;53:683-694.

- Qamar AA, Grace ND, Groszmann RJ, et al. Platelet count is not a predictor of the presence or development of gastroesophageal varices in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2008;47:153-159.

- Madhotra R, Mulcahy HE, Willner I, Rueben A. Prediction of esophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:81-85.

- Castera L, Le Bail B, Roudot-Thoraval F, et al. Early detection in routine clinical practice of cirrhosis and oesophageal varices in chronic hepatitis C: comparison of transient elastography (FibroScan) with standard laboratory tests and non-invasive scores. J Hepatol. 2009;50:59-68.

- Schreibman I, Meitz K, Kunselman AR, Downey M, Le T, Riley T. Defining the threshold: new data on the ability of capsule endoscopy to discriminate the size of esophageal varices. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:220-226.

- Perri RE, Chiorean MV,Fidler JL, et al. A prospective evaluation of computerized tomographic (CT) scanning as a screening modality for esophageal varices. Hepatology. 2008;47:1587-1594.

- Lipp MJ, Broder A, Hudesman D, et al. Detection of esophageal varices using CT and MRI. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2696-2700.

- Lipp MJ, Broder A, Hudesman D, et al. Detection of esophageal varices using CT and MRI. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2696-2700.

- Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T, eds. Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease. 6th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 1999. 845-901.

- Sherlock S, Dooley J. Diseases of the Liver and Biliary System. 10th ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Science; 1997. 135-80.

- Gore RM, Livine MS, eds. Textbook of Gastrointestinal Radiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 2000. 454-63, 2082.

- Luketic VA, Sanyal AJ. Esophageal varices. I. Clinical presentation, medical therapy, and endoscopic therapy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2000 Jun. 29(2):337-85.

- Wojtowycz AR, Spirt BA, Kaplan DS, Roy AK. Endoscopic US of the gastrointestinal tract with endoscopic, radiographic, and pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1995 Jul. 15(4):735-53.

- Bosch J, Berzigotti A, Garcia-Pagan JC, Abraldes JG. The management of portal hypertension: rational basis, available treatments and future options. J Hepatol. 2008;48(supp 1):S68-S92.

- Qamar AA, Grace ND, Groszmann RJ, et al. Platelet count is not a predictor of the presence or development of gastroesophageal varices in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2008;47:153-159.

- Rowen K. Zetterman. The Clinical Management of Gastroesophageal Varices. Medscape. Available from: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/756964_4 (Accessed on 2019 Jan 30)