EPIDEMIOLOGY

Portal hypertension is a frequent manifestation of liver cirrhosis. According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), liver cirrhosis accounted for almost 30,000 deaths in the United States in 2007, making it the 12th leading cause of US deaths.(1) The frequency of gastroesophageal varices directly correlates with the severity of the liver disease from 40% in Child class A to 85% in Child class C.(2) Liver disease demonstrates a sex predilection, with males making up more than 60% of patients with chronic liver disease and cirrhosis.(3) Unfortunately, total population-based prevalence data for portal hypertension in Pakistan is not available. In a small study conducted at Liaquat Medical College it was found that the prevalence of Portal hypertension was 42% among cirrhotic patients.(4)

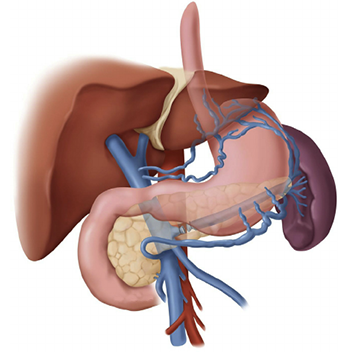

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Two most important causes of the portal hypertension worldwide:(5)

-

- Cirrhosis

- Hepatic schistosomiasis (Non cirrhotic)

Portal hypertension is caused by a combination of two simultaneously occurring hemodynamic processes.

- Increased vascular resistance (Intrahepatic in case of cirrhosis)

- Increased blood flow to splanchnic areas

- Increased vascular resistance (Intrahepatic resistance in case of cirrhosis)

There are two components to the increased resistance, structural changes and dynamic changes.(6) structural changes occur when there is distortion of the liver microcirculation by fibrosis, nodules, angiogenesis, and vascular occlusion. Dynamic changes occur when there is contraction of the activated hepatic stellate cells and myofibroblasts that surround hepatic sinusoids and are in the fibrous septa and vascular smooth muscle cells of the hepatic vasculature. The dynamic changes are thought to be due to increased production of vasoconstrictors (e.g. endothelins, angiotensin-II, norepinephrine, thromboxane A2) and reduced release of endothelial vasodilators (e.g. nitric oxide).

Increased blood flow to splanchnic areas

The second factor that contributes to the pathogenesis of portal hypertension is an increase in blood flow in the portal veins. This increase is established through splanchnic arteriolar vasodilation caused by an excessive release of endogenous vasodilators (e.g. endothelial, neural, and humoral).

The increase in portal blood flow aggravates the increase in portal pressure; the increased flow contributes to the ability of portal hypertension to exist despite the formation of an extensive network of portosystemic collaterals that may divert as much as 80% of the portal blood flow. Manifestations of splanchnic vasodilatation include increased cardiac output, arterial hypotension, and hypervolemia. This explains the rationale for treating portal hypertension with a low-sodium diet and diuretics to attenuate the hyperkinetic state.

Pathophysiology of portal hypertension due to non-cirrhotic components

Schistosomiasis in one to the most common causes of non-cirrhotic portal hypertension worldwide.

Schistosomiasis:

Out of the three main schistosomiasis species, S. japonicum and S. mansoni are known to cause liver disease. S. japonicum is distributed widely throughout the world, predominantly in Asia. S. hematobium affects mainly the urinary tract, although at advanced stages the liver can develop portal fibrosis. The acute stage of schistosomiasis mimics acute bacterial infection and is accompanied by marked eosinophilia. Chronic hepatic schistosomiasis is characterized by features of portal hypertension; esophageal varices, hepatomegaly, and splenomegaly with hypersplenism. The diagnosis of schistosomiasis can be made by the detection of schistosomal ova in the stool. Management includes treating underlying parasitic infection and preventing or treating the consequences of portal hypertension.

NATURAL HISTORY(7)

The natural history of cirrhosis can be divided into a preclinical phase and a subsequent clinical phase. The preclinical phase is usually prolonged over several years; once clinical events such as the development of ascites, encephalopathy, and variceal bleeding occur, the remaining course of the disease is much shorter and usually fatal.

Portal hypertension is crucial in the transition from the preclinical to the clinical phase of cirrhosis: it is a contributive mechanism of ascites and encephalopathy and a direct cause of variceal bleeding and bleeding-related death.

Bleeding from ruptured esophagogastric varices is the most severe complication of cirrhosis and is the cause of death in about one third of cirrhotic patients.

SIGN AND SYMPTOMS(8)

Symptoms of liver disease include the following:

- Weakness, tiredness, and malaise

- Anorexia

- Sudden and massive bleeding, with or without shock on presentation

- Nausea and vomiting

- Weight loss – This symptom is common with acute and chronic liver disease; it is mainly due to anorexia and reduced food intake and regularly accompanies end-stage liver disease, when a loss of muscle mass and adipose tissue is often a striking feature

- Abdominal discomfort and pain – Usually felt in the right hypochondrium or under the right lower ribs (front, side, or back) and in the epigastrium or the left hypochondrium

- Jaundice or dark urine

- Edema and abdominal swelling

- Pruritus – Usually associated with cholestatic conditions, such as extrahepatic biliary obstruction, primary biliary cirrhosis, sclerosing cholangitis, cholestasis of pregnancy, and benign, recurrent cholestasis

- Spontaneous bleeding and easy bruising

- Symptoms of encephalopathy – These include disturbance of the sleep-wake cycle; deterioration in intellectual function, memory loss, and, finally, an inability to communicate effectively at any level; personality changes; and, possibly, displays of inappropriate or bizarre behavior

- Impotence and sexual dysfunction

- Muscle cramps – Common in patients with cirrhosis

- Spider angiomas

The presence of complications of portal hypertension can be ascertained by determining whether the following are present:

- Hematemesis or melena – May indicate gastroesophageal variceal bleeding or bleeding from portal gastropathy

- Mental status changes – Such as lethargy, increased irritability, and altered sleep patterns; these may indicate the presence of portosystemic encephalopathy

- Increasing abdominal girth – May indicate ascites formation

- Abdominal pain and fever – May indicate spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, although this disease also presents without symptoms

- Hematochezia – May indicate bleeding from portal colopathy

Physical examination

Signs of portosystemic collateral formation include the following:

- Dilated veins in the anterior abdominal wall – May indicate umbilical epigastric vein shunts

- Venous pattern on the flanks – May indicate portal-parietal peritoneal shunting

- Caput medusae (tortuous paraumbilical collateral veins)

- Rectal hemorrhoids

- Ascites – Shifting dullness and fluid wave (if a significant amount of ascitic fluid is present) (9)

- Paraumbilical hernia

Signs of a hyper-dynamic circulatory state include the following:

- Bounding pulses

- Warm, well-perfused extremities

- Arterial hypotension

- Flow murmur over the pericardium

Other signs of portal hypertension and esophageal varices include the following:

- Pallor – May suggest active internal bleeding

- Parotid enlargement – May be related to alcohol abuse and/or malnutrition

- Cyanosis of the tongue, lips, and peripheries – Due to low oxygen saturation

- Dyspnea and tachypnea

- Telangiectasis of the skin, lips, and digits

- Gynecomastia – Results from failure of the liver to metabolize estrogen, resulting in a sex hormone imbalance; loss of pubic and axillary hair may also be observed

- Fetor hepaticus – Occurs in portosystemic encephalopathy of any cause (e.g. cirrhosis)

- Small-sized liver

- Venous hums – Continuous noises audible in patients with portal hypertension; may be present as a result of rapid, turbulent flow in collateral veins

- Tarry stool – During the rectal examination, obtain a stool sample for visual inspection; a black, soft, tarry stool on the gloved examining finger suggests upper gastrointestinal bleeding

- Hemorrhoids

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS(8)

When evaluating a patient with portal hypertension, also consider the following conditions:

- Cirrhosis of any etiology (viral hepatitis, autoimmune cirrhosis, alcohol-related cirrhosis, primary biliary cirrhosis, etc.)

- Hepatic infiltrative diseases (e.g. Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, sarcoidosis)

- Hepatoportal arteriovenous fistula

- Portal vein obstruction

- Portal vein occlusion (e.g. portal vein thrombosis)

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Severe congestive heart failure (cardiac cirrhosis)

- Splenic vein thrombosis

- Veno-occlusive disease

- Budd-Chiari syndrome

- Schistosomiasis

- Chronic pancreatitis

Patients who present with upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding can be approached as whether the bleeding is variceal or non-variceal. Not all upper GI bleeding in cirrhotic patients are from variceal hemorrhage. It should also be noted that peptic ulcer disease is present more frequently in cirrhotic patients than noncirrhotic patients.(10) The differential diagnosis of variceal hemorrhage includes the following:

- Acute gastric erosions

- Duodenal ulcers

- Gastric cancer

- Gastric ulcers

- Mallory-Weiss tear

- Nasogastric tube trauma

- Portal hypertensive gastropathy – It is a relatively uncommon cause of significant bleeding

Laboratory studies

Laboratory studies are directed towards investigating the etiologies of cirrhosis, which is the most common cause of portal hypertension. The rate and volume of bleeding in the patient should be assessed.

Gain venous access and obtain blood for immediate hematocrit measurement. Obtain a type and cross-match for possible blood product transfusion. Measure the platelet count and prothrombin time (PT), send blood for renal and liver function tests (LFTs), and measure serum electrolyte levels.

Complete blood count (CBC)

The presence of anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia may be present in patients with cirrhosis. Anemia may be secondary to bleeding, nutritional deficiencies, or bone marrow suppression secondary to alcoholism. Pancytopenia can result from hypersplenism, a common complication in patients with portal hypertension. Serial monitoring of the hemoglobin and hematocrit value is useful in patients with suspected ongoing gastrointestinal bleeding.

Liver disease–associated tests

Abnormal liver function can be approached as a transaminitis (an elevation of the plasma activity of aspartate aminotransferase [AST] and alanine aminotransferase [ALT]) or cholestasis (an elevation of bilirubin, especially conjugated bilirubin, with or without increased alkaline phosphatase [ALP] activity), both of which may occur in cirrhosis. However, normal liver function studies do not exclude liver disease, as a “burned out” liver (i.e. one that loses features of disease activity) may not give rise to aminotransferase activity.

Type and cross-match

Transfusion with packed red blood cells (RBCs) and fresh frozen plasma (FFP) are usually required in patients with massive variceal bleeding.

Coagulation tests

Coagulation studies include PT, partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and international normalized ratio (INR). Because the synthetic function of the liver is impaired in cirrhotic patients, coagulopathy with prolonged PT and PTT is expected; INR is also used to assess the severity and prognosis of the liver disease through Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score calculation. Prolonged INR is suggestive of impaired hepatic synthetic function.

Blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and electrolytes

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels may be elevated in patients with esophageal bleeding; BUN is also used in calculating the Blatchford bleeding score in the initial evaluation, and serum creatinine results are used in calculating the MELD score.

Arterial blood gas (ABG) and pH measurements

A high anion gap may suggest hyperlactatemia or hyperammonemia.

Hepatic and viral hepatitis serologies

Obtain viral hepatitis serologies, particularly hepatitis B and C. These may help in assessing the cause of liver cirrhosis.

Other laboratory tests may include the following:

- Albumin levels – Hypoalbuminemia is commonly found owing to the liver’s impaired synthetic function

- Antinuclear antibody, antimitochondrial antibody, antismooth muscle antibody

- Iron indices

- Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency

- Ceruloplasmin, 24-hour urinary copper – Consider this test only in individuals aged 3-40 years who have unexplained hepatic, neurologic, or psychiatric disease

Duplex Doppler Ultrasonography

On duplex Doppler ultrasonography, features suggestive of hepatic cirrhosis with portal hypertension include the following:

- Nodular liver surface – However, this finding is not specific for cirrhosis; it can also be observed with congenital hepatic fibrosis and nodular regenerative hyperplasia

- Splenomegaly

- Collateral circulation

Limitations of ultrasonography include the fact that the reproducibility of data is problematic and that many variables, such as circadian rhythm, meals, medications, and the sympathetic nervous system, affect portal hemodynamics. Moreover, significant interobserver and intraobserver variation exist in quantitative ultrasonographic measurement.

CT scanning

Computed tomography (CT) scanning is a useful qualitative study when ultrasonographic evaluations are inconclusive. CT scanning is not affected by the patient’s body habitus or the presence of bowel gas. With improvement of spiral CT scanning and 3-dimensional (3-D) angiographic reconstructive techniques, portal vasculature may be visualized more accurately.

Findings suggestive of portal hypertension include collaterals arising from the portal system and dilatation of the inferior vena cava (IVC).

Limitations of CT scanning include the fact that it cannot demonstrate the venous and arterial flow profile and that intravenous contrast agents cannot be used in patients with renal failure or contrast allergy.

MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides qualitative information similar to that from CT scanning when Doppler ultrasonographic findings are inconclusive. MRI angiography detects the presence of portosystemic collaterals and obstruction of portal vasculature. MRI also provides quantitative data on portal venous and azygos blood flow.

Liver-spleen scan

Liver-screen scanning is described for historical interest only, because this technique has been superseded by ultrasonography and CT scanning. Liver-spleen scans use technetium sulfur colloid, which is taken up by cells in the reticuloendothelial system. A colloidal shift from the liver to the spleen or bone marrow is suggestive of increased portal pressure.

Limitations of these scans include the fact that portal hypertension cannot be ruled out in the absence of this shift. In addition, liver-spleen scans lack spatial resolution.

Hemodynamic Measurement of Portal Pressure

Direct portal measurements are usually not performed, due to their invasive nature, the risk of complications, and the interference of anesthetic agents with portal hemodynamics.

More commonly, measurement of the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) is performed; this is an indirect measurement that closely approximates portal venous pressure. Monitoring HVPG is useful in assessing the patient’s response to treatment, progression of the disease, and prognosis. Reduction in HVPG of greater than 20% of baseline or to less than 12 mm Hg significantly reduces mortality and the risk of recurrent variceal hemorrhage.

Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Endoscopy (esophagogastroduodenoscopy [EGD]) is an essential diagnostic and therapeutic tool at an early stage to formulate the management plan for patients with esophageal varices. If active variceal bleeding or an adherent clot is observed, variceal hemorrhage can be diagnosed confidently. The presence of any of the following risk factors warrants a screening endoscopy to search for varices :

- International normalized ratio (INR) level of 1.5 or greater

- Hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) measurement of 10 mm Hg or greater

- Portal vein diameter of more than 13 mm

- Presence of thrombocytopenia

The presence of variceal red color signs (e.g. cherry red spots, red wale markings [longitudinal red streaks on varices], blue varices) and the “white nipple sign” (platelet fibrin plug overlying a varix, resembling a white nipple) indicates an increased risk of rebleeding.

Transient elastography

Although measurement of hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) and upper endoscopy are considered the criterion standards for assessment of portal hypertension, ultrasonography-based transient elastography is a novel noninvasive technology to detect clinically significant portal hypertension. Further studies are being conducted to validate this.

THERAPY CONSIDERATION

Treatment is directed at the cause of portal hypertension. Gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage is the most dramatic and lethal complication of portal hypertension; therefore, most of the following discussion focuses on the treatment of variceal hemorrhage. Medical care includes emergent treatment, primary and secondary prophylaxis, and surgical intervention.

Pharmacologic therapy for portal hypertension includes the use of beta-blockers, most commonly propranolol and nadolol. Endoscopic procedures such as sclerotherapy and variceal ligation can be used to prevent the recurrence of variceal hemorrhage. Surgical care includes the use of decompressive shunts, devascularization procedures, and liver transplantation. Decompressive shunts and devascularization procedures are mainly rescue therapies.

Management of patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites but without hemorrhage includes a low-sodium diet and diuretics.

TREATMENT OPTIONS(8)

Surgical Intervention

Surgery has no role in primary prophylaxis. Its role in acute variceal bleeding is exceedingly limited, because therapy with endoscopic treatment controls bleeding in 90% of patients. A transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is a viable option and is less invasive for patients whose bleeding is not controlled. However, if TIPS is not available, then staple transection of the esophagus is an option when endoscopic treatment and pharmacologic therapy have failed.

Surgical interventions include the following:

- Portosystemic shunts

- Devascularization procedures

- Orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) – Treatment of choice in patients with advanced liver disease

Decompressive Shunts

Surgical shunts provide better control of rebleeding when compared to the combination therapy of beta-blocker and endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL). However, these shunts are associated with higher incidence of hepatic encephalopathy and should be reserved for Child class A patients with recurrent bleeding despite adequate combination therapy. Decompressive shunts include total portal systemic shunts, partial portal systemic shunts, and other selective shunts.

Total portal systemic shunts: Total portal systemic shunts include any shunt larger than 10 mm in diameter between the portal vein (or one of its main tributaries) and the inferior vena cava (IVC) (or one of its tributaries).

For the side-to-side portacaval shunt, the portal vein and the infrahepatic IVC are mobilized after dissection and anastomosed. All portal flow is directed through the shunt, with the portal vein itself acting as an outflow from the obstructed hepatic sinusoids. Excellent control of bleeding and ascites is achieved in more than 90% of patients. Encephalopathy (rate of 40-50%) and progressive liver failure are possible. The procedure has relatively limited indications, which include massive variceal bleeding with ascites or acute Budd-Chiari syndrome without evidence of liver failure.

Partial portal systemic shunts: Partial portal systemic shunts reduce the size of the anastomosis of a side-to-side shunt to 8 mm in diameter. Portal pressure is reduced to 12 mm Hg, and portal flow is maintained in 80% of patients.

The operative approach is similar to that for side-to-side portacaval shunts, except the interposition graft must be placed between the portal vein and the IVC.

Selective shunts: Selective shunts provide selective decompression of gastroesophageal varices to control bleeding while at the same time maintaining portal hypertension to maintain portal flow to the liver. One example is the distal splenorenal shunt, which is the most commonly used decompressive operation for refractory variceal bleeding; it is used primarily in patients who present with refractory bleeding and continue to have good liver function. The distal splenorenal shunt decompresses the gastroesophageal varices through the short gastric veins, the spleen, and the splenic vein to the left renal vein.

Portal hypertension is maintained in the splanchnic and portal venous system, and the shunt maintains portal flow to the liver. This type of shunt provides the best long-term maintenance of some portal flow and liver function, with a lower incidence of encephalopathy (10-15%) compared with total shunts. The operation produces ascites because the retroperitoneal lymphatics are diverted.

Devascularization Procedures

Devascularization is rarely performed but may have a role in patients with portal and splenic vein thrombosis who are not suitable candidates for shunt procedures and who continue to have variceal bleeding despite endoscopic and pharmacologic treatment.

Devascularization procedures consist of the transabdominal devascularization of the lower 5 cm of the esophagus and the upper two thirds of the stomach, with staple gun transection of the lower esophagus) (e.g. splenectomy, gastroesophageal devascularization, and esophageal transection [at times]).

The incidence of liver failure and encephalopathy is low following devascularization procedures, presumably because of better maintenance of portal flow. However, these procedures are rarely performed but may have a role in patients with portal and splenic vein thrombosis who are not suitable candidates for shunt procedures and who continue to have variceal bleeding despite endoscopic and pharmacologic treatment.

Splenectomy: The spleen is one of the major inflow paths to gastroesophageal varices. Splenectomy allows better access to the gastric fundus and the distal esophagus to complete the devascularization. Portal vein thrombosis of as much as 20% is reported following splenectomy. Ascites is a frequent early postoperative complication because portal hypertension is maintained.

Gastroesophageal devascularization (Sugiura procedure): Gastroesophageal devascularization should devascularize the whole greater curve of the stomach from the pylorus to the esophagus and the upper two thirds of the lesser curve of the stomach. The esophagus should be devascularized for a minimum of 7 cm.

In patients who have undergone extensive and repeated sclerotherapy, the gastroesophageal junction is thickened and the ability to perform a satisfactory transection is limited.

Liver Transplantation

Liver transplantation should be considered for patients with end-stage liver disease (e.g. cirrhotic patients with Child-Pugh score =7 or Model for End-Stage Liver Disease [MELD] score =15). The selection of candidates is dictated by the patient’s clinical status, etiology of cirrhosis (viral hepatitis, alcoholic, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, cholestatic liver disease), abstinence from alcohol, and availability of a donor organ.

Liver transplantation is the ultimate shunt, because it relieves portal hypertension, prevents variceal rebleeding, and manages ascites and encephalopathy by restoring liver function. It is the treatment modality that has significantly improved the outcome of patients with Child-Pugh class C disease and variceal bleeding.

In most patients, it is impractical to use liver transplantation to treat portal hypertension, because these individuals can be managed successfully with lesser methods. Therefore, the use of transplantation must be based on appropriate patient selections, as follows :

- For patients with Child class A disease, shunt surgery is recommended

- For patients with Child class B disease, shunt surgery or a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is appropriate

- For people with Child C class disease, TIPS or OLT is recommended

Secondary Prophylaxis

Secondary prophylaxis is used to prevent rebleeding. Variceal hemorrhage has a 2-year recurrence rate of approximately 80%.

Nonselective beta-blockers:

Propranolol and nadolol significantly reduce the risk of rebleeding and are associated with prolongation of survival. Studies comparing propranolol with sclerotherapy in the prevention of variceal rebleeding demonstrated comparable rates of variceal rebleeding and survival, but sclerotherapy was associated with significantly more complications.

Endoscopic sclerotherapy: Endoscopic sclerotherapy is usually performed at weekly intervals. Approximately 4-5 sessions are required for the eradication of varices, which is achieved in nearly 70% of patients. Endoscopic variceal ligation: Endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) is considered the endoscopic treatment of choice in the prevention of rebleeding. Sessions are repeated at 7- to 14-day intervals until variceal obliteration (which usually requires 2-4 sessions). This procedure is associated with lower rebleeding rates and a lower frequency of esophageal strictures. Fewer sessions are required to achieve variceal obliteration than are required for sclerotherapy.

Combination of EVL and pharmacologic therapy: Combination of beta-blocker therapy with EVL is considered to the best option for secondary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage. Rather than titrating beta-blockers to goal reduction in heart rate, doses should be titrated to the maximal tolerated dose, because a goal reduction in heart rate may not correlate to a reduction in hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG). EVL should be repeated every 1-2 weeks until complete variceal obliteration occurs; then, endoscopy can be repeated every 3-6 months to evaluate for recurrence and for the need to repeat EVL.

Medication Summary

The main advantages to using vasoactive agents include the ability of these drugs to treat variceal bleeding in the emergency department, lower portal pressure, and offer the endoscopist a clearer view of varices because of less active bleeding. Vasoactive agents represent an ideal treatment for sources of portal hypertensive bleeding other than esophageal varices (e.g. gastric varices >2 cm below the gastroesophageal junction or portal hypertensive gastropathy).

The vasoconstrictors somatostatin and octreotide are used to treat acute bleeding in patients with portal hypertension before performing endoscopy. Intravenous infusions of octreotide will lower portal blood pressure and can prevent rebleeding during the patient’s initial hospitalization. Vasodilators such as isosorbide mononitrate (ISMN) reduce intrahepatic vascular resistance without decreasing the peripheral or portal-collateral resistance.

Beta-blockers, which include propranolol, nadolol, and timolol, are used to provide primary and secondary prophylaxis. Beta-blockers lower the cardiac output (via blockade of beta1 adrenoreceptors) and cause splanchnic vasoconstriction (via blockade of vasodilatory adrenoreceptors of the splanchnic circulation), reducing portal and collateral blood flow.

Somatostatin Analogs

Somatostatin, an orphan drug, is a naturally occurring tetradecapeptide isolated from the hypothalamus and from pancreatic and enteric epithelial cells. Through vasoconstriction, somatostatin diminishes blood flow to the portal system, thus decreasing variceal bleeding. It has effects similar to those of vasopressin but does not cause coronary vasoconstriction. Somatostatin has an initial half-life of 1-3 minutes and is rapidly cleared from the circulation.

Somatostatin analogs inhibit the secretion of hormones involved in vasodilation. Octreotide is a synthetic octapeptide. Compared with somatostatin, octreotide has similar pharmacologic actions with greater potency and longer duration of action. In the US, octreotide is used off-label for the management of variceal hemorrhage.

Octreotide:

Octreotide, a synthetic octapeptide, acts primarily on somatostatin receptor subtypes II and V. It inhibits growth hormone secretion and has a multitude of other endocrine and nonendocrine effects, including the inhibition of glucagon, vasoactive intestinal peptide, and GI peptides. Octreotide has greater potency and a longer duration of action than somatostatin.

Beta-Blockers, Nonselective

Nonselective beta-blocking agents decrease hepatic arterial and portal venous perfusion. Beta-adrenergic blockers may block the effect of vasodilators, decrease platelet adhesiveness and aggregation, and increase the release of oxygen to tissues.

Nonselective beta-blockers have been shown to prevent bleeding in more than 50% of patients with medium or large varices. These agents exert a moderate effect on the reduction of portal flow, and smaller effects on the increase in portal resistance and decrease on portal pressure.

Propranolol is used off-label for primary prophylaxis — in combination with endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) — for esophageal varices. This agent is also indicated for secondary prophylaxis for esophageal varices.

Propranolol: Propranolol is a non-cardioselective beta-blocker that reduces portal pressure through the reduction of portal and collateral blood flow. It competes with adrenergic neurotransmitters (e.g. catecholamines) at sympathetic receptor sites. Similar to atenolol and metoprolol, propranolol blocks sympathetic stimulation mediated by beta1-adrenergic receptors in the heart and vascular smooth muscles.

Nadolol: Nadolol is a non-cardioselective beta-blocker that reduces portal pressure through the reduction of portal and collateral blood flow.

Timolol: Timolol is a non-cardioselective beta-blocker that reduces portal pressure through the reduction of portal and collateral blood flow.

Vasopressin-Related

Vasoconstrictors reduce portal blood flow and/or increase resistance to variceal blood flow inside the varices. Therefore, these drugs reduce blood flow in the gastroesophageal collaterals because of their vasoactive effects on the splanchnic vascular system. When used in combination with nitrates, the efficacy and safety of vasoconstrictors have been shown to improve. However, their use may be limited as the risk of adverse events is higher with combination therapy.

Terlipressin is widely used in Europe but has not received FDA approval for use in the United States. This is a synthetic analogue of vasopressin. It is the only pharmacologic agent shown to reduce mortality from variceal bleeding. Terlipressin has longer biologic activity than vasopressin. It significantly reduces portal and variceal pressure and azygos flow. The drug is beneficial when combined with sclerotherapy. Terlipressin also has the advantage of preserving renal function, which is a particularly important feature in patients with cirrhosis.

Vasopressin: Vasopressin has vasopressor and antidiuretic hormone (ADH) activity. It increases water resorption at the distal renal tubular epithelium (ADH effect) and promotes smooth muscle contraction throughout the vascular bed of the renal tubular epithelium (vasopressor effects). However, vasoconstriction is also increased in splanchnic, portal, coronary, cerebral, peripheral, pulmonary, and intrahepatic vessels. Vasopressin decreases portal pressure in portal hypertension.

A notable adverse effect of this agent is coronary artery constriction, which may dispose patients with coronary artery disease to cardiac ischemia. This can be prevented with the concurrent use of nitrates. Vasopressin is rarely used.

Vasodilators

Vasodilators have been shown to exert a small effect on the reduction of portal flow, an increase in portal resistance, and decrease on portal pressure. These agents reduce intrahepatic vascular resistance without decreasing peripheral or portal-collateral resistance.

Nitrates, however, technically work by decreasing resistance. They decrease portal flow by decreasing mean arterial pressure. Oral nitroglycerin is used off-label for the management of variceal bleeding.

Nitroglycerin PO: Nitroglycerin causes relaxation of vascular smooth muscle by stimulating intracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate production. The result is a decrease in blood pressure.

GOALS OF TREATMENT

The goals of pharmacotherapy are to reduce mortality and morbidity, and prevent complications associated with acute bleeding related to portal hypertension.

GUIDELINES

To view, “Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: Report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: Stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension”, please click on below link:

http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0168827815003499/1-s2.0-S0168827815003499-main.pdf?_tid=89fa1c6a-ca5c-11e5-9300-00000aab0f6c&acdnat=1454493630_6d1238f74baebfa7460dd2f1bbdf237f

To view, “UK guidelines on the management of variceal haemorrhage in cirrhotic patients”, please click on below link:

http://gut.bmj.com/content/early/2015/05/12/gutjnl-2015-309262.full.pdf+html

CONSULTATION AND LONG TERM MONITORING

Consider early consultation with a gastroenterologist and a surgeon, particularly for patients with active bleeding from esophageal varices. Consultation with a hepatologist and transplant surgery should be considered in patients with Child class B or C disease or a high Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score. Good coordination among gastroenterologists, interventional radiologists, critical care team, and surgeons is essential.

To prevent recurrent variceal hemorrhage, patients with portal hypertension should have endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) sessions scheduled until complete obliteration of varices is achieved. EVL sessions are repeated at 7- to 14-day intervals. These usually require 2-4 sessions for complete obliteration of varices.

As noted in Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, periodic surveillance endoscopy should be performed in patients with cirrhosis as follows:

- Repeat endoscopy annually in decompensated patients, patients with alcohol abuse, and patients with stigmata of variceal bleeding

- Repeat endoscopy at 1-2 years to evaluate the progression of varices in compensated patients with small varices

- Repeat endoscopy at 2-3 years to evaluate for the development of varices in compensated patients without varices

PRECAUTIONS

Maintaining good nutritional habits and keeping a healthy lifestyle may help patient avoid portal hypertension. Following advices should be given to patient:

- Alcohol intake should strongly be discouraged, especially in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Available resources for alcohol rehabilitation should be provided, along with any prophylaxis for alcohol withdrawal symptoms, when indicated.

- Do not take any over-the-counter or prescription drugs or herbal medicines without first consulting your doctor or nurse. (Some medications may make liver disease worse.)

- Follow the dietary guidelines given by your health care provider, including eating a low-sodium (salt) diet. You will probably be required to consume no more than 2 grams of sodium per day. Reduced protein intake may be required if confusion is a symptom. A dietitian can create a meal plan for you.

Unless contraindicated, all patients with esophageal varices should take beta-blockers to reduce the risk of bleeding. Patients should also be educated about the adverse effects of beta-blockers and the possible risks of their abrupt discontinuation.

Advise patients who have ascites of the risk of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis during an episode of acute variceal bleeding.

REFERENCES

- Yoon Y, Yi H. Surveillance report no. 88: liver cirrhosis mortality in the United States, 1970-2007. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Available at http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/surveillance88/Cirr07.htm. Accessed: Jul 17 2012.

- Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey WD, and the Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007 Sep. 102(9):2086-102.

- Kim WR, Brown RS Jr, Terrault NA, El-Serag H. Burden of liver disease in the United States: summary of a workshop. Hepatology. 2002 Jul. 36(1):227-42.

- Suhail Ahmed Almani, A. Sattar Memon, Amir Iqbal Memon, M. Iqbal Shah, M. Qasim Rahpoto, Rahim Solangi, Cirrhosis of liver: Etiological factors, complications and prognosis, JLUMHS MAY – AUGUST 2008.

- Berzigotti A, Seijo S, Reverter E, Bosch J. Assessing portal hypertension in liver diseases. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 7:141.

- Garcıá -Pagán JC, Gracia-Sancho J, Bosch J. Functional aspects on the pathophysiology of portal hypertension in cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2012; 57:458.

- De Franchis R, Primignani M. Natural history of portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis. Clinics in liver disease. 2001 Aug 1;5(3):645-63.

- Jesus Carale. Portal hypertension. Medscape. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/182098-overview (Accessed on 2019 Jan 30)

- Hou W, Sanyal AJ. Ascites: diagnosis and management. Med Clin North Am. 2009 Jul. 93(4):801-17, vii.

- Dite P, Labrecque D, Fried M, et al, for the World Gastroenterology Organisation (WGO). World Gastroenterology Organisation practice guideline: esophageal varices. Munich, Germany: World Gastroenterology Organisation; 2008. Available at http://guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=13000. Accessed: August 6, 2012.