EPIDEMIOLOGY

Over 1.8 million new colorectal cancer cases and 881,000 deaths are estimated to occur in 2018, accounting for about 1 in 10 cancer cases and deaths. Overall, colorectal cancer ranks third in terms of incidence but second in terms of mortality. (1)

Recent study has shown that Pakistan falls into a low incidence region/category for colorectal cancer.(2) The crude incidence rate is 3.2% in both males and females. Most significantly, however, the incidence appears to be rising, particularly in males. This study also suggested that given an aging population, a strong tradition of consanguineous marriages, and a high prevalence of colorectal cancer risk factors, including a trend towards a more “westernized” dietary intake, this low incidence may, in fact, be an artifact. This data may also be an underestimation of colorectal cancer in Pakistan because the registry is voluntary and some cases may have gone unreported.(3)

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY (4)

Genetically, colorectal cancer represents a complex disease, and genetic alterations are often associated with progression from premalignant lesion (adenoma) to invasive adenocarcinoma. The early event is a mutation of APC (adenomatous polyposis gene), which was first discovered in individuals with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). The protein encoded by APC is important in the activation of oncogene c-myc and cyclin D1, which drives the progression to malignant phenotype. Although FAP is a rare hereditary syndrome accounting for only about 1% of cases of colon cancer, APC mutations are very frequent in sporadic colorectal cancers.

In addition to mutations, epigenetic events such as abnormal DNA methylation can also cause silencing of tumor suppressor genes or activation of oncogenes. These events compromise the genetic balance and ultimately lead to malignant transformation.

Other important genes in colon carcinogenesis include the KRAS oncogene, chromosome 18 loss of heterozygosity (LOH) leading to inactivation of SMAD4(DPC4), and DCC (deleted in colon cancer) tumor suppression genes. Chromosome arm 17p deletion and mutations affecting the p53 tumor suppressor gene confer resistance to programmed cell death (apoptosis) and are thought to be late events in colon carcinogenesis.

A subset of colorectal cancers is characterized with deficient DNA mismatch repair. This phenotype has been linked to mutations of genes such as MSH2, MLH1, andPMS2. These mutations result in so-called high frequency microsatellite instability (H-MSI), which can be detected with an immunocytochemistry assay. H-MSI is a hallmark of hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer syndrome (HNPCC, Lynch syndrome), which accounts for about 6% of all colon cancers. H-MSI is also found in about 20% of sporadic colon cancers.

NATURAL HISTORY(5)

Colorectal cancer arises from a precursor lesion, the adenomatous polyp, which forms in a field of epithelial cell hyperproliferation and crypt dysplasia. Progression from this precursor lesion to colorectal cancer is a multistep process, accompanied by alterations in several suppressor genes that result in abnormalities of cell regulation, and has a natural history of 10–15 years. Environmental factors and inherited susceptibility play major roles in this sequence of events. As a result of familial and genetic studies, now there is a better understanding of various high-risk groups and the application of screening methods to these individuals and to people at average risk. In the future, further identification of genetically predisposed individuals and colonoscopic screening of the general population may provide new opportunities for control of colorectal cancer through secondary prevention, and a better understanding of lifestyle factors and their modification will lead to improved strategies for primary prevention.

SIGN AND SYMPTOMS

History: Because of increased emphasis on screening practices, colon cancer is now often detected before it starts to cause symptoms. In more advanced cases, common clinical presentations include iron-deficiency anemia, rectal bleeding, abdominal pain, change in bowel habits, and intestinal obstruction or perforation. Right-sided lesions are more likely to bleed and cause diarrhea, while left-sided tumors are usually detected later and may present as bowel obstruction.(4)

Physical Examination: Physical examination findings can be very nonspecific (e.g. fatigue, weight loss) or normal early in the course of colon cancer. In more advanced cases, any of the following may be present:(4)

- Abdominal tenderness

- Macroscopic rectal bleeding

- Palpable abdominal mass

- Hepatomegaly

- Ascites

When colorectal cancer does turn out to be the cause, symptoms often appear only after the cancer has grown or spread. That’s why it’s best to be tested for colorectal cancer before ever having any symptoms. Colorectal cancer that’s found through screening – testing that’s done on people with no symptoms – is usually easier to treat. Screening can even prevent some colorectal cancers by finding and removing pre-cancerous growths called polyps.(6)

RATIONALE FOR SCREENING

The American Cancer Society 2018 guideline for colorectal cancer screening recommends that average-risk adults aged 45 years and older undergo regular screening with either a high-sensitivity stool-based test or a structural (visual) exam, based on personal preferences and test availability. As a part of the screening process, all positive results on non-colonoscopy screening tests should be followed up with timely colonoscopy. (7)

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS(8)

Once a CRC is suspected, the next test can be a colonoscopy, barium enema, or computed tomography colonography. However, examination of tissue is required to establish the diagnosis; this is usually accomplished by colonoscopy.

Histopathologically, the majority of cancers arising in the colon and rectum are adenocarcinomas.

Colonoscopy: Colonoscopy is the most accurate and versatile diagnostic test for CRC, since it can localize and biopsy lesions throughout the large bowel, detect synchronous neoplasms, and remove polyps. Synchronous CRCs, defined as two or more distinct primary tumors diagnosed within six months of an initial CRC, separated by normal bowel, and not due to direct extension or metastasis, occur in 3 to 5 percent of patients. The incidence is somewhat lower (approximately 2.5 percent) when patients with Lynch syndrome are excluded; the presence of synchronous cancers should raise the clinical suspicion for Lynch Syndrome or MUTYH-associated polyposis.

When viewed through the endoscope, the vast majority of colon and rectal cancers are endoluminal masses that arise from the mucosa and protrude into the lumen. The masses may be exophytic or polypoid. Bleeding (oozing or frank bleeding) may be seen with lesions that are friable, necrotic, or ulcerated. Circumferential or near-circumferential involvement of the bowel wall correlates with the so-called «apple-core» description seen on radiologic imaging.

A minority of neoplastic lesions in the gastrointestinal tract (both in asymptomatic and symptomatic individuals) are nonpolypoid and relatively flat or depressed. For endoscopically visible lesions, methods for tissue sampling include biopsies, brushings, and polypectomy. For lesions that are completely removed endoscopically (with polypectomy, endoscopic mucosal resection, or endoscopic submucosal dissection), tattooing is important for subsequent localization if an invasive neoplasm is found, and additional local therapy is needed. Tattoos are typically placed adjacent to or a few centimeters distal to the lesion, with the location being documented in the colonoscopy report. Large, laterally spreading colonic polyps can now be safely removed endoscopically, provided they meet endoscopic criteria that predict their benign nature.

If a malignant obstruction precludes a full colonoscopy preoperatively, the entire residual colon should be examined soon after resection.

In the absence of an obstruction, where colonoscopy is incomplete, additional options include CT colonography or Pill Cam colon 2, a wireless colon video endoscopy capsule approved for CRC screening, although its use in patients with symptoms suggestive of CRC (e.g. anemia, rectal bleeding, weight loss) is controversial.

As noted above, given the limitations to timely colonoscopy in many health care settings and the nonspecific nature of most colorectal (cancer) symptoms, there is emerging interest in using fecal immunochemical tests for occult blood (iFOBT) using a low threshold of fecal hemoglobin to maximize sensitivity in order to stratify symptomatic patients who need more urgent diagnostic colonoscopy. This approach is supported by a limited amount of data showing that a negative result on iFOBT has a high negative predictive value for ruling out CRC. However, this approach is not in widespread use.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy: Over the last 50 years, a gradual shift toward right-sided or proximal colon cancers has been observed both in the United States and internationally, with the greatest increase in incidence in cecal primaries. Because of this, and because of the high frequency of synchronous CRCs, flexible sigmoidoscopy is generally not considered to be an adequate diagnostic study for a patient suspected of having a CRC, unless a palpable mass is felt in the rectum. In such cases, a full colonoscopy will still be needed to evaluate the remainder of the colon for synchronous polyps and cancers. Nevertheless, screening for CRC using a flexible sigmoidoscope is one of the few modalities that have been proven through randomized controlled trials to reduce CRC mortality and incidence.

CT colonography: CT colonography (also called virtual colonoscopy or CT colography) provides a computer-simulated endoluminal perspective of the air-filled distended colon. The technique uses conventional spiral or helical CT scan or magnetic resonance images acquired as an uninterrupted volume of data, and employs sophisticated postprocessing software to generate images that allow the operator to fly-through and navigate a cleansed colon in any chosen direction. CT colonography requires a mechanical bowel prep that is similar to that needed for barium enema, since stool can simulate polyps.

CT colonography has been evaluated in patients with incomplete colonoscopy and as an initial diagnostic test in patients with symptoms suggestive of CRC.

- Incomplete colonoscopy: Non-completion rates for diagnostic colonoscopy in symptomatic patients are approximately 11 to 12 percent. Reasons for incompleteness include the inability of the colonoscope to reach the tumor or to visualize the mucosa proximal to the tumor for technical reasons (e.g. partially or completely obstructing cancer, tortuous colon, poor preparation) and patient intolerance of the examination. In this setting, CT colonography is useful for the detection of CRC and can provide a radiographic diagnosis, although it can overcall stool as masses in poorly distended or poorly prepared colons; it also lacks the capability for biopsy or removal of polyps.

CT colonography should be restricted to patients who are able to pass flatus and capable of tolerating the oral preparation. For clinically obstructed patients, a gastrointestinal (GI) protocol abdominal CT scan is a good alternative to CT colonography.

- Initial diagnostic test: Systematic reviews of screening studies conducted in asymptomatic patients suggest that both CT colonography and colonoscopy have similar diagnostic yield for detecting CRC and large polyps. Comparison of the benefits and costs of the two procedures depends on other factors, one of the most important of which is the need for additional investigation after CT colonography and the exposure to radiation, which is particularly important where recurrent scanning over time may be contemplated such as in screening.

Abnormal results with CT colonography should be followed up by colonoscopy for excision and tissue diagnosis, or for smaller lesions, additional surveillance with CT colonography. There is controversy as to the threshold size of a polyp that would indicate the need for (interventional) colonoscopy and polypectomy. CT colonography also has the ability to detect extracolonic lesions, which might explain symptoms and provide information as to the tumor stage, but also could generate anxiety and cost for unnecessary investigation and may have a low yield of clinically important pathology.

PILLCAM 2: A colon capsule for CRC screening has been approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in Europe and by the US Food and Drug Administration. In the United States, it is approved for use in patients who have had an incomplete colonoscopy. While its role in screening for CRC is still uncertain, it could be considered in a patient with an incomplete colonoscopy who lacks obstruction.

Laboratory tests: Although CRC is often associated with iron deficiency anemia, its absence does not reliably exclude the disease. There is no diagnostic role for other routine laboratory test, including liver function tests, which lack sensitivity for detection of liver metastases.

- Tumor markers: A variety of serum markers have been associated with CRC, particularly carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). However, all these markers, including CEA, have a low diagnostic ability to detect primary CRC due to significant overlap with benign disease and low sensitivity for early-stage disease.

An expert panel on tumor markers in breast and colorectal cancer convened by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommended that neither serum CEA nor any other marker, including CA 19-9, should be used as a screening or diagnostic test for CRC. A similar recommendation has been made by the European Group on Tumor Markers. (9)

However, CEA levels do have value in the follow-up of patients with diagnosed CRC. ASCO guidelines recommend that serum CEA levels be obtained preoperatively in most patients with demonstrated CRC to aid in surgical treatment planning, posttreatment follow-up, and in the assessment of prognosis:

- Serum levels of CEA have prognostic utility in patients with newly diagnosed CRC. Patients with preoperative serum CEA >5 ng/mL have a worse prognosis, stage for stage, than those with lower levels, although at least some data suggest that elevated preoperative CEA that normalizes after resection is not an indicator of poor prognosis.

- Elevated preoperative CEA levels that do not normalize following surgical resection imply the presence of persistent disease and the need for further evaluation.

Furthermore, serial assay of postoperative CEA levels should be performed for five years for patients with stage II and III disease if they may be a potential candidate for surgery or chemotherapy if metastatic disease is discovered. A rising CEA level after surgical resection implies recurrent disease and should prompt follow-up radiologic imaging.

Staging: Once the diagnosis of colorectal cancer (CRC) is established, the local and distant extent of disease is determined to provide a framework for discussing therapy and prognosis. A review of the biopsy specimen is important prior to making a decision about the need for clinical staging studies and surgical resection, especially for a cancerous polyp. Polyps with an area of invasive malignancy that have been completely removed and lack associated adverse histologic features (positive margin, poor differentiation, lymphovascular invasion) have a low risk of lymphatic and distant metastases; in such patients, polypectomy alone may be adequate. This is more easily determined if the polyp is pedunculated.

TNM staging system: The tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging system of the combined American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) / Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) is the preferred staging system for CRC.

The most recent (eighth edition, 2017) revision of the TNM staging classification contains few changes compared with the earlier 2010 seventh edition. The M1c stage has been introduced to reflect peritoneal carcinomatosis as a poor prognostic factor, and nodal micrometastases (tumor clusters >0.2 mm in diameter) are now scored as positive given the results of a meta-analysis demonstrating a poor prognosis in these patients.

In addition, the definition of tumor deposits as they apply to regional nodal status is clarified. This version also acknowledges the following factors, which are important to consider when making decisions about treatment but are not yet incorporated into the formal staging criteria:

- Preoperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels.

- Tumor regression score, which reflects the pathologic response to preoperative radiotherapy, chemoradiotherapy, or chemotherapy and the status of the circumferential resection margin for rectal cancers.

- Lymphovascular and perineural invasion.

- Microsatellite instability, which reflects deficiency of mismatch repair enzymes and is both a prognostic factor and predictive of a lack of response to fluoropyrimidine therapy.

- Mutation status of KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF, because mutations in these genes are associated with lack of response to agents targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR).

Radiographic, endoscopic (including biopsy), and intraoperative findings can be used to assign a clinical stage, while assessment of the pathologic stage (termed pT, pN, pM) requires histologic examination of the resection specimen. Preoperative radiation and chemotherapy (as are often undertaken for locally advanced rectal cancer) can significantly alter clinical staging; as a result, posttherapy pathologic staging is designated with a yp prefix (i.e. ypT, ypN).

PATIENT SELECTION FOR TREATMENT(10)

Surgery is the only curative modality for localized colon cancer (stage I-III). Surgical resection potentially provides the only curative option for patients with limited metastatic disease in liver and/or lung (stage IV disease), but the proper use of elective colon resections in non-obstructed patients with stage IV disease is a source of continuing debate.

Adjuvant chemotherapy is standard for patients with stage III disease. Its use in stage II disease is controversial, with ongoing studies seeking to confirm which markers might identify patients who would benefit. At present, the role of radiation therapy is limited to palliative therapy for selected metastatic sites such as bone or brain metastases.

TREATMENT OPTIONS(10)

Surgical Care

Surgery is the only curative modality for localized colon cancer (stage I-III) and potentially provides the only curative option for patients with limited metastatic disease in liver and/or lung (stage IV disease). The general principles for all operations include removal of the primary tumor with adequate margins including areas of lymphatic drainage.

For lesions in the cecum and right colon, a right hemicolectomy is indicated. During a right hemicolectomy, the ileocolic, right colic, and right branch of the middle colic vessels are divided and removed. Care must be taken to identify the right ureter, the ovarian or testicular vessels, and the duodenum. If the omentum is attached to the tumor, it should be removed en bloc with the specimen.

For lesions in the proximal or middle transverse colon, an extended right hemicolectomy can be performed. In this procedure, the ileocolic, right colic, and middle colic vessels are divided and the specimen is removed with its mesentery. For lesions in the splenic flexure and left colon, a left hemicolectomy is indicated. The left branch of the middle colic vessels, the inferior mesenteric vein, and the left colic vessels along with their mesenteries are included with the specimen. For sigmoid colon lesions, a sigmoid colectomy is appropriate. The inferior mesenteric artery is divided at its origin, and dissection proceeds toward the pelvis until adequate margins are obtained. Care must be taken during dissection to identify the left ureter and the left ovarian or testicular vessels.

Total abdominal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis may be required for patients with any of the following:

- Hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer syndrome (HNPCC)

- Attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)

- Metachronous cancers in separate colon segments

Total abdominal colectomy may also be indicated for some patients with acute malignant colon obstructions in whom the status of the proximal bowel is unknown.

Laparoscopic surgery

The advent of laparoscopy has revolutionized the surgical approach to colonic resections for cancers. Large prospective randomized trials have found no significant differences between open and laparoscopic colectomy with regard to intraoperative or postoperative complications, perioperative mortality rates, readmission or reoperation rates, or rate of surgical wound recurrence. Oncologic outcomes (cause-specific survival, disease recurrence, number of lymph nodes harvested) are likewise comparable.

Metastatic colorectal cancer

Chemotherapy rather than surgery has been the standard management for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. The proper use of elective colon/rectal resections in nonobstructed patients with stage IV disease is a source of continuing debate.

Medical oncologists properly note the major drawbacks to palliative resection, such as loss of performance status and risks of surgical complications that potentially lead to delay in chemotherapy. However, surgeons understand that elective operations have lower morbidity than emergent operations on patients who are receiving chemotherapy. Curative-intent resections of liver metastases have significantly improved long-term survival, with acceptable postoperative morbidity, including in older patients.

Hepatic arterial infusion (HAI) of chemotherapeutic agents such as floxuridine (FUDR) is a consideration following partial hepatectomy. During the past decade, colonic stents have introduced an effective method of palliation for obstruction in patients with unresectable liver metastasis.

Ablation

Although resection is the only potentially curative treatment for patients with colon metastases, other therapeutic options for those who are not surgical candidates include thermal ablation techniques. Cryotherapy uses probes to freeze tumors and surrounding hepatic parenchyma. It requires laparotomy and can potentially results in significant morbidity, including liver cracking, thrombocytopenia, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) uses probes that heat liver tumors and the surrounding margin of tissue to create coagulation necrosis. RFA can be performed percutaneously, laparoscopically, or through an open approach. Although RFA has minimal morbidity, local recurrence is a significant problem and correlates with tumor size.

Adjuvant Therapy

Benefits of adjuvant therapy

The standard chemotherapy for patients with stage III and some patients with stage II colon cancer for the last two decades consisted of 5-fluorouracil in combination with adjuncts such as levamisole and leucovorin. This approach has been tested in several large randomized trials and has been shown to reduce individual 5-year risk of cancer recurrence and death by about 30%.

Alternative regimens

Two large randomized trials (MOSAIC and NASBP-C06) investigated the addition of oxaliplatin to fluorouracil and demonstrated a significant improvement in 3-year disease-free survival for patients with stage III colon cancer. The addition of irinotecan to fluorouracil in the same patient population provided no benefit based on the results from two large randomized trials (CALGB 89803 and PETACC 3).

The randomized XACT study demonstrated the noninferiority of capecitabine compared with fluorouracil/leucovorin as adjuvant therapy for patients with stage III colon cancer. A large trial comparing capecitabine plus oxaliplatin versus FOLFOX has completed accrual, but survival data have not yet been reported.

Adjuvant therapy in stage II colon cancer

The role of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer is controversial. Surgery alone is usually curative for stage II colon cancer, but approximately 20-30% of these patients develop tumor recurrence and ultimately die of metastatic disease. The American Society of Clinical Oncology does not recommend the routine use of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage II colon cancer, and instead recommends encouraging these patients to participate in clinical trials.

Therapy for Metastatic Disease

Combination regimens provide improved efficacy and prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with metastatic colon cancer. The advent of new classes of active drugs and biologics for colorectal cancer has pushed the expected survival for patients with metastatic disease from 12 months two decades ago to about 22 months currently.

In September 2015, the FDA approved tipiracil/trifluridine for metastatic colorectal cancer. Efficacy and safety were evaluated in the phase III RECOURSE trial, an international, randomized, double-blind study involving 800 patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer. Patients had received chemotherapy with a fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin, irinotecan, bevacizumab, and—for patients with KRAS wild-type tumors—cetuximab or panitumumab. The primary efficacy end point of the study was median overall survival, which was 7.1 months with tipiracil/trifluridine vs 5.3 months with placebo (P < 0.001). The secondary end point was progression-free survival, which was 2 months with tipiracil/trifluridine vs 1.7 months with placebo.(11)

Biologic Agents

Biologic agents used in the treatment of colon cancer include monoclonal antibodies against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), as well as a kinase inhibitor and a decoy receptor for VEGF. Such agents include the following:

- Bevacizumab

- Cetuximab

- Nivolumab

- Panitumumab

- Pembrolizumab

- Regorafenib

- Ziv-aflibercept

- Bevacizumab

Radiation Therapy

Although radiation therapy remains a standard modality for patients with rectal cancer, it has only a limited role in colon cancer. Radiation therapy is not used in the adjuvant setting, and in metastatic settings it is used only for palliative therapy in selected metastatic sites such as bone or brain metastases.

HER2-positive disease

HER2 is overexpressed in approximately 3% of colorectal cancers overall and in 5-14% of RAS/BRAF–wild type colorectal tumors. Experimental therapeutic approaches for tumors that have HER2 overexpression have included trastuzumab plus lapatinib and trastuzumab plus pertuzumab.

GOALS OF THERAPY

For many colorectal cancers, the goal of treatment is to cure the cancer. If cure is not possible, treatment may be used to shrink the cancer or keep it under control for as long as possible. Treatment can also improve your quality of life by helping control the symptoms of the disease. The goals of colorectal cancer treatment can include:

- Remove the cancer in the colon or rectum

- Remove or destroy tumors in other parts of the body

- Kill or stop the growth or spread of colorectal cancer cells

- Prevent or delay the cancer’s return

- Ease symptoms from the cancer, such as pain or eating problems caused by pressure on organs

GUIDE LINES

To view, “Early colon cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up”, please click on below link:

https://academic.oup.com/annonc/article/24/suppl_6/vi64/161392

To view, “Follow-Up Care, Surveillance Protocol, and Secondary Prevention Measures for Survivors of Colorectal Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Endorsement”, please click on below link:

http://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/JCO.2013.50.7442?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed

To view, “Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) Guidelines on Diagnosis and management of colorectal cancer”, please click on below link:

https://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign126.pdf

To view, “NCCN Guidelines on Colon Cancer, Version 2 – 2018”, please click on below link:

http://www.jnccn.org/content/16/4/359.full.pdf+html

To view, “American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) – Colorectal cancer guidelines”, please click on below link:

https://www.gastro.org/guidelines/colorectal-cancer

CONSULTATION AND LONG TERM MONITORING (10)

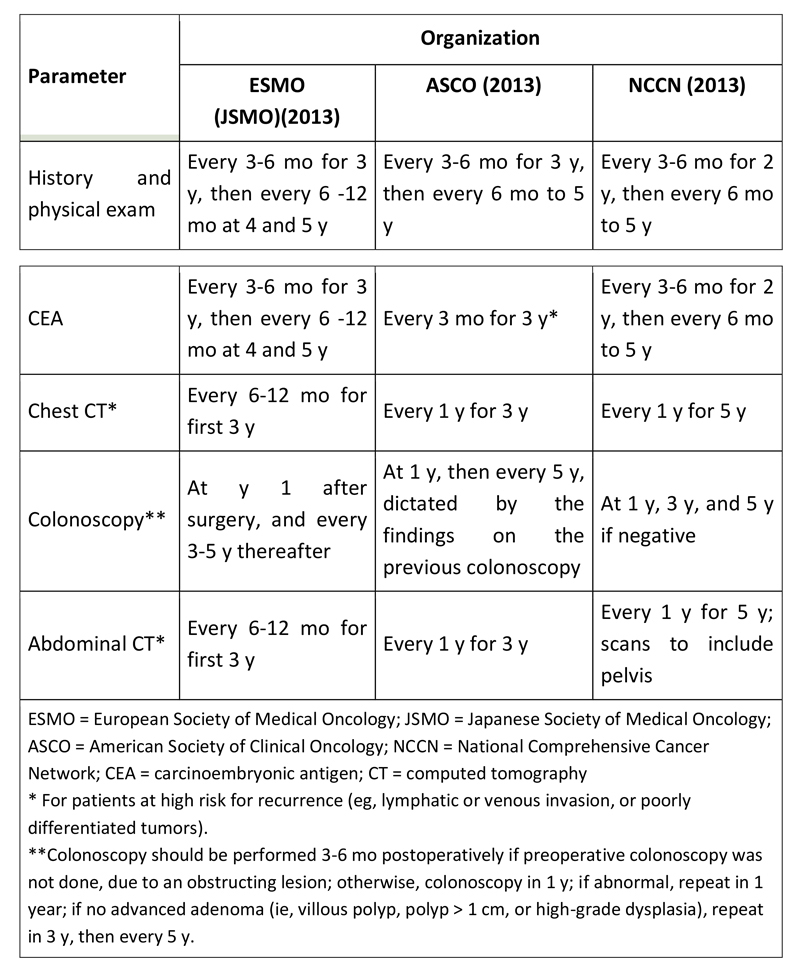

Pooled analysis from several large adjuvant trials showed that 85% of colon cancer recurrences occur within 3 years after resection of primary tumor, with 95% occurring within 5 years. Therefore, patients with resected colon cancer (stage II and III) should undergo regular surveillance for at least 5 years following resection. Recommendations for post-treatment surveillance, from the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO),(12) the American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO),(13) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)(14) are compared in Table , below.

Table: Surveillance recommendations for stage II and III colon cancer

Follow up should be guided by the patient’s presumed risk of recurrence and functional status. Testing at the more frequent end of the range should be considered for patients at high risk. Patients with severe comorbid conditions that make them ineligible for surgery or systemic therapy should not undergo surveillance testing.

Cancer Care Ontario published guidelines for the follow-up care of survivors of stages II and III colorectal cancer, and these were endorsed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. The recommendations include the following:

- Surveillance is especially important in the initial 2-4 years following treatment, when most recurrences occur

- Patients should be followed for 5 years, and regular reviews of medical history, physical examination, and carcinoembryonic antigen testing should be performed every 3-6 months

- Annual computed tomography (CT) scanning of the abdomen and chest should be performed for 3 years

- Pelvic CT scanning should be performed in patients with rectal cancer annually for 3-5 years

- In patients who have not received pelvic radiation, a rectosigmoidoscopy should be performed every 6 months for 2-5 years

- A surveillance colonoscopy should be performed approximately 1 year after initial surgery

- Patients should be counseled to maintain a healthy body weight, be physically active, and follow a healthy diet.

PRECAUTIONS

Advice following precautions to the patient:

Get screened for colorectal cancer: Screenings are tests that look for cancer before signs and symptoms develop. Colorectal screenings can often find growths called polyps that can be removed before they turn into cancer. These tests also can find colon or rectal cancer earlier, when treatments are more likely to be successful. The American Cancer Society recommends testing starting at age 45 for people at average risk.

Eat lots of vegetables, fruits, and whole grains: Diets that include lots of vegetables, fruits, and whole grains have been linked with a decreased risk of colon or rectal cancer. Eat less red meat (beef, pork, or lamb) and processed meats (hot dogs and some luncheon meats), which have been linked with an increased risk of colorectal cancer.

Get regular exercise. If you are not physically active, you have a greater chance of developing colon or rectal cancer. Increasing your activity may help reduce your risk.

Maintain healthy weight: Overweight or obese increases the risk of getting and dying from colon or rectal cancer. Eating healthier and increasing physical activity can help control weight.

Don’t smoke: Long-term smokers are more likely than non-smokers to develop and die from colon or rectal cancer.

Limit alcohol: Alcohol use has been linked with a higher risk of colorectal cancer. The American Cancer Society recommends no more than 2 drinks a day for men and 1 drink a day for women. A single drink amounts to 12 ounces of beer, 5 ounces of wine or 1½ ounces of 80-proof distilled spirits (hard liquor).

REFERENCES

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel R, Torre L, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2018;68(6):394-424.

- Bhurgri Y, Khan T, Kayani N, Ahmad R, Usman A, Bhurgri A, Bashir I, Hasan SH, Zaidi S. Incidence and current trends of colorectal malignancies in an unscreened, low risk Pakistan population. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:703–708

- Ahmed F. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening in the developing world: The view from Pakistan. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2013;4(4):83-5.

- Dragovich T. Colon Cancer [Internet]. New York: Medscape [updated: 2018 July 31; cited 2019 Jan 10] Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/277496-overview#a4

- Winawer SJ. Natural history of colorectal cancer. The American journal of medicine. 1999 Jan 25;106(1):3-6.

- American Cancer Society. Signs and Symptoms of Colorectal Cancer [internet]. Atlanta: American Cancer Society [updated: 2018 May 30; cited 2019 Jan 10] Available from https://www.cancer.org/latest-news/signs-and-symptoms-of-colon-cancer.html

- American Cancer Society. Colorectal Cancer Screening Guidelines [internet]. Atlanta: American Cancer Society [cited 2019 Jan 10] Available from https://www.cancer.org/health-care-professionals/american-cancer-society-prevention-early-detection-guidelines/colorectal-cancer-screening-guidelines.html

- Macrae FA, Bendell J. Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and staging of colorectal cancer [internet]. Waltham, Massachusetts: UptoDate [updated 2018 Oct 22; cited 2019 Jan 10] Available from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-presentation-diagnosis-and-staging-of-colorectal cancer?search=clinical%20manifestation%20of%20colorectal%20cancer&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H2937024

- Duffy MJ, van Dalen A, Haglund C, et al. Clinical utility of biochemical markers in colorectal cancer: European Group on Tumour Markers (EGTM) guidelines. Eur J Cancer 2003; 39:718

- Colon Cancer Treatment & Management [Internet]. New York: Medscape [updated: 2018 July 31; cited 2019 Jan 10] Available from:https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/277496-treatment

- Mayer RJ, Van Cutsem E, Falcone A, Yoshino T, Garcia-Carbonero R, Mizunuma N, et al. Randomized trial of TAS-102 for refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015 May 14. 372 (20):1909-19

- Labianca R, Nordlinger B, Beretta GD, Mosconi S, Mandalà M, Cervantes A, et al. Early colon cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013 Oct. 24 Suppl 6:vi64-72

- Meyerhardt JA, Mangu PB, Flynn PJ, Korde L, Loprinzi CL, Minsky BD, et al. Follow-Up Care, Surveillance Protocol, and Secondary Prevention Measures for Survivors of Colorectal Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Endorsement. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Nov 12

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Colon Cancer. Available at http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#site. Version 2.2018 — March 14, 2018; Accessed: March 27, 2018.