EPIDEMIOLOGY

Overall, head and neck cancer accounts for more than 550,000 cases annually worldwide.(1) Males are affected significantly more than females with a ratio ranging from 2:1 to 4:1. Mouth and tongue cancers are more common in the Indian subcontinent; nasopharyngeal cancer is more common in Hong Kong; and pharyngealand/or laryngeal cancers are more common in other populations; these factors contribute disproportionately to the overall cancer burden in these Asian countries.(2,3).

In the United States, head and neck cancer accounts for 3 percent of malignancies, with approximately 63,000 Americans developing head and neck cancer annually and 13,000 dying from the disease.(3) In Europe, there were approximately 250,000 cases (estimated 4 percent of the cancer incidence) and 63,500 deaths in 2012. The incidence of laryngeal cancer, but not oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer, is approximately 50 percent higher in African American men.(4)

The social and cultural habits are the main cause of the remarkable increase in HN cancer in Pakistan. HN cancers are more prevalent in men as compared to women. The HN cancer in Pakistan is mainly attributed to discrete demographic profile, risk elements, eating patterns and family history. The foremost factors of risk are linked with cigarette smoking, alcoholic drinks and tobacco chewing like paan, gutka, etc. The actual burden of HN cancer in Pakistan is 18.74% of all new cancer cases recorded during 2004 -2014. The data is collected from HN cancer patients who are diagnosed from September 2011 till May 2012 in the Institute of Nuclear medicine and Oncology, Lahore Pakistan.(5)

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

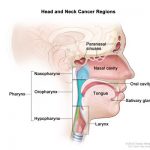

Cancers that are known collectively as head and neck cancers usually begin in the squamous cells that line the moist, mucosal surfaces inside the head and neck (for example, inside the mouth, the nose, and the throat). These squamous cell cancers are often referred to as squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Head and neck cancers can also begin in the salivary glands, but salivary gland cancers are relatively uncommon. Salivary glands contain many different types of cells that can become cancerous, so there are many different types of salivary gland cancer.(6)

Cancers of the head and neck are further categorized by the area of the head or neck in which they begin. These areas are described below and labeled in the image of head and neck cancer regions.(6)

Oral cavity: Includes the lips, the front two-thirds of the tongue, the gums, the lining inside the cheeks and lips, the floor (bottom) of the mouth under the tongue, the hard palate (bony top of the mouth), and the small area of the gum behind the wisdom teeth.

Pharynx: The pharynx (throat) is a hollow tube about 5 inches long that starts behind the nose and leads to the esophagus. It has three parts: the nasopharynx (the upper part of the pharynx, behind the nose); the oropharynx (the middle part of the pharynx, including the soft palate (the back of the mouth), the base of the tongue, and the tonsils); thehypopharynx (the lower part of the pharynx).

Larynx: The larynx, also called the voicebox, is a short passageway formed by cartilage just below the pharynx in the neck. The larynx contains the vocal cords. It also has a small piece of tissue, called the epiglottis, which moves to cover the larynx to prevent food from entering the air passages.

Paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity: The paranasal sinuses are small hollow spaces in the bones of the head surrounding the nose. The nasal cavity is the hollow space inside the nose.

Salivary glands: The major salivary glands are in the floor of the mouth and near the jawbone. The salivary glands produce saliva.

Head and neck cancer regions. Illustrates location of paranasal sinuses, nasal cavity, oral cavity, tongue, salivary glands, larynx, and pharynx (including the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and hypopharynx).(6)

TRANSMISSION

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is a sexually transmitted infection that can infect the oropharynx (tonsils and back of throat), anus, and genitals. There are many types of HPV. HPV can cause cancer, warts or have no effect. In some people, oral HPV infection leads to HPV-OSCC (HPV-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer) after many years. It is recommended that oropharyngeal tumors be tested for HPV. Smoking and alcohol use can also cause oropharyngeal cancer.

While oral HPV infection may be transmitted mouth to mouth or vertically from an infected mother to her child, oral HPV infection is typically transmitted sexually.

NATURAL HISTORY(7)

Oral Cavity: The most common presenting complaint is a sore in the mouth or on the lips. One-third of patients present with a neck mass.

The differential diagnosis includes other malignancies and benign diseases or lesions. Other malignancies to be considered include salivary gland tumors, sarcoma, lymphoma, and melanoma. Benign diseases include pyogenic granuloma, tuberculous disease, aphthous ulcers, and chancres.

Benign mucosal lesions include papillomas and keratoacanthomas, which may be exophytic or infiltrative. The exophytic lesions are less aggressive. The infiltrative papillomas and keratoacanthomas are more often associated with destruction of surrounding tissues and structures. These lesions may progress to malignancy.

The lips: The most frequent presentation is a slow-growing tumor of the lower lip that may bleed and hurt. Physical examination must include assessment of hypoesthesia in the distribution of the mental nerve (cutaneous sensation of the chin area).

The tongue: The most common presenting symptom in patients with cancer of the tongue is a persistent, nonhealing ulcer with or without associated pain. Other symptoms include difficulty with deglutition and speech. There may be a history of leukoplakia, especially in younger women.

- Rate of growth: Cancer of the tongue seems to grow more rapidly than other oral cavity cancers. Tongue cancers may grow in an infiltrative or exophytic fashion. The infiltrative tumors may be quite large at presentation.

- Lesion thickness: Thicker lesions have a worse prognosis than thin cancers, and lesion thickness is a more important prognostic factor than simple tumor stage. The incidence of clinically occult cervical metastases to the neck is significantly higher when the tumor thickness exceeds 4 mm.

- Cervical metastases: Cervical metastases occur more frequently from tongue cancer than from any other tumor of the oral cavity. At initial evaluation, 40% of patients have node metastases.

The floor of the mouth: Patients usually present with a painful mass located near the oral tongue. Because these lesions do not cause pain until they are deep, they are frequently advanced at presentation.

Extension of disease into the soft tissues of the submandibular triangle is not uncommon. Fixation of the tumor to bone suggests possible mandibular involvement, which may be evaluated further with CT imaging. Changes in the mental foramen can be distinct or demonstrate slight asymmetry when compared with the contralateral anatomy. Restricted tongue mobility reflects invasion into the root of the tongue. Palpation demonstrates the depth of infiltration much better than does inspection alone.

Tumors near the midline may obstruct the duct of the submandibular gland, leading to swelling and induration in the neck, which may be difficult to distinguish from lymph node metastases. Level I nodes are the first-echelon metastatic sites.

The base of the tongue: The base of the tongue is notorious for lesions that infiltrate deeply into muscle and are advanced at diagnosis. This finding is probably due to the relatively asymptomatic anatomic location. Thus, bimanual oral examination with digital palpation is a critical part of the physical examination.

All oropharyngeal cancers have a strong propensity to spread to the lymph nodes, and tumors arising at the base of the tongue are no exception. Approximately 70% of patients with T1 primary base of the tongue tumors have clinically palpable disease in the neck, and 20% to 30% have palpable, bilateral lymph node metastases. The risk of nodal metastases increases with increasing T stage and approaches 85% for T4 lesions.

Tonsils and tonsillar pillar: Tonsillar fossa tumors tend to be more advanced and more frequently metastasize to the neck than do tonsillar pillar cancers. At presentation, 55% of patients with fossa tumors have N2 or N3 disease, and contralateral metastases are common.

Hypopharynx: Hypopharyngeal tumors produce few symptoms until they are advanced (> 70% are stage III or IV at presentation). They may cause a sore throat, otalgia, a change in voice, odynophagia, or an isolated neck mass. Subtle changes on physical examination, including pooling of secretions, should be regarded with concern.

Supraglottis: Tumors close to the glottis produce symptoms earlier than do tumors at other subsites, usually hoarseness. In contrast, nearly 60% of patients with supraglottic tumors have T3 or T4 primary tumors at presentation.

The supraglottis has a rich lymphatic network. There is an associated high incidence of lymph node metastases in early-stage tumors (40% for T1 tumors). The incidence of metastases in patients with clinically N0 neck cancer is about 15%. The incidence of bilateral cervical lymph node involvement is about 10%, and this rate increases to 60% for anterior tumors. The neck is a frequent site of recurrence in patients with supraglottic malignancies.

Glottis: The cure rate for tumors of the true vocal cords is high. These cancers produce symptoms early and, thus, most are small when detected. Approximately 60% are T1 and 20% are T2. Normal cord mobility implies invasion of disease limited to the submucosa. Deeper tumor invasion results in impaired vocal cord motion; this finding is most common in the anterior two-thirds of the vocal cord.

Subglottis: These cancers tend to be poorly differentiated and, because the region is clinically “silent,” most present as advanced lesions (~70% are T3–T4). The subglottis also has rich lymphatic drainage, and the incidence of cervical metastases is 20% to 30%.

Nasopharynx: A mass in the neck is the presenting complaint in 90% of patients. Other presenting symptoms include a change in hearing, sensation of ear stuffiness, tinnitus, nasal obstruction, and pain.

SIGN AND SYMPTOMS (8)

People with head and neck cancer often experience the following symptoms or signs. Sometimes, people with head and neck cancer do not have any of these changes. Or, the cause of a symptom may be a different medical condition that is not cancer.

- Swelling or a sore that does not heal; this is the most common symptom

- Red or white patch in the mouth

- Lump, bump, or mass in the head or neck area, with or without pain

- Persistent sore throat

- Foul mouth odor not explained by hygiene

- Hoarseness or change in voice

- Nasal obstruction or persistent nasal congestion

- Frequent nose bleeds and/or unusual nasal discharge

- Difficulty breathing

- Double vision

- Numbness or weakness of a body part in the head and neck region

- Pain or difficulty chewing, swallowing, or moving the jaw or tongue

- Jaw pain

- Blood in the saliva or phlegm, which is mucus discharged into the mouth from respiratory passages

- Loosening of teeth

- Dentures that no longer fit

- Unexplained weight loss

- Fatigue

- Ear pain or infection

RATIONALE FOR SCREENING(9)

To date there is no evidence to support screening of asymptomatic patients for head and neck cancer, but, not infrequently, asymptomatic potentially premalignant lesions are found by dentists and their staff at routine oral examinations. 10% of leukoplakia (white mucosal patches) may develop into a carcinoma if left untreated. Inflamed red patches (erythroplakia) is potentially more sinister with a 30% of chance of developing malignancy.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

Initial evaluation: The initial assessment of the primary tumor is based upon a thorough history and combination of inspection, palpation, indirect mirror examination, or direct flexible laryngoscopy. Physical examination should include careful assessment of the nasal cavity and oral cavity with visual examination and/or palpation of mucous membranes, the floor of the mouth, the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, tonsillar fossae and tongue base (best seen on mirror examination or flexible laryngoscopy), palate, buccal and gingival mucosa, and posterior pharyngeal wall.

External auditory canal examination and anterior rhinoscopy should be undertaken. For patients with non-laryngeal lesions but a strong alcohol or smoking history, flexible laryngoscopy is commonly undertaken to visualize potential other lesions and to document vocal cord mobility. A metastatic work-up with appropriate imaging is recommended for all newly-diagnosed head and neck cancer patients, with particular attention to regional lymph node spread. An examination under anesthesia often is performed to best characterize the extent of the tumor, to look for synchronous second primary tumors, and to take biopsies for a tissue diagnosis.

Following are the diagnostic options for head and neck cancer

Fine needle aspiration biopsy: Fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNA) is frequently used to make an initial tissue diagnosis of a head and neck cancer when a patient present with a neck mass (metastatic cervical lymph node) without an obvious primary mucosal/upper aerodigestive tract site. This technique has high sensitivity and specificity and a diagnostic accuracy that ranges from 89 to 98 percent.(10) Nondiagnostic aspirations occur in 5 to 16 percent of cases, most commonly in cystic neck masses, as is common in the presentation of patients with HPV associated oropharyngeal cancers.

Imaging studies: Imaging studies (computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), PET, and integrated PET/CT) are important for assessing the degree of local infiltration, involvement of regional lymph nodes, and presence of distant metastases or second primary tumors.

CT scan: CT can identify tumors of the head and neck based upon either anatomic distortion or specific tumor enhancement. In general, tumors enhance more than normal head and neck structures except for mucosa, extraocular muscles, and blood vessels.(11)

Magnetic resonance imaging: MRI provides superior soft tissue definition compared with CT (12) and can often provide information that is complementary to CT. For example, MRI can provide more accurate definition of tumors of the tongue and is more sensitive for superficial tumors. MRI is also better than CT for discriminating tumor from mucus and in detecting bone marrow invasion.(13) For this reason, MRI can be useful for evaluation of cartilage invasion, particularly for non-ossified cartilage that can pose difficulty for CT. MRI is superior to CT for evaluation of perineural spread, skull base invasion, and intracranial extension of head and neck cancer. MRI may also provide additional benefits compared with CT in the evaluation of the base of tongue and parotid glands.

PET and integrated PET/CT: With PET, injected positron-emitting radionuclides, such as fluorine-18, are taken up by metabolically or functionally active tissues. PET images are created by detecting these emissions by an array of detectors and then using reconstruction techniques to create a three dimensional image. The most commonly used agent is 18F-flourodeoxyglucose (FDG), which is taken up into cells in different concentrations depending on the relative metabolism of different tissues. It is fairly specific for tumors because metabolic rates are very high in many tumors.

Evaluation for distant metastases: A component of the initial staging evaluation for patients with new or recurrent head and neck cancer is the search for distant metastases. The reported incidence is between 2 and 26 percent and varies based on locoregional control, nodal involvement (number and presence of extracapsular extension), primary site (particularly hypopharynx), histologic grade, and T stage.

Distant metastases at initial diagnosis are usually asymptomatic; the most common sites are the lungs followed by the liver and bone. Screening tests such as chest x-ray, serum alkaline phosphatase, and liver function tests are insensitive to the presence of distant metastases.

Until recently, CT scan was the most sensitive method to screen for distant metastases in patients with head and neck cancer, identifying malignant findings in between 4 and 19 percent of newly diagnosed cases.(14)

THERAPY CONSIDERATION

A multidisciplinary approach is required for optimal decision making, treatment planning, and post-treatment response assessment. This should include surgeons, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists, as well as dentists, speech/swallowing pathologists, dieticians, psychosocial oncology, prosthodontists, and rehabilitation therapists. Specifically, a multidisciplinary tumor board affects diagnostic and treatment decisions in a significant number of patients with newly diagnosed head and neck tumors. Furthermore, complex cases of head and neck cancer should be treated at high-volume centers whenever possible, where expertise in each of these disciplines may be better.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

The treatment plan for an individual patient depends on a number of factors, including the exact location of the tumor, the stage of the cancer, and the person’s age and general health.

Treatment for head and neck cancer can include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or a combination of treatments. Followings are the options available for the treatment of head and neck cancer.

Surgery: Larynx-preserving surgical techniques to treat patients with early laryngeal cancer include partial open laryngectomy, transoral laser microsurgery (TOLM), and transoral robotic surgery. Larynx-preserving surgery should be undertaken only when the surgeon is confident that tumor-free margins can be obtained because postoperative RT may compromise functional outcomes, particularly after open surgical procedures. Transoral laser surgery is a minimally invasive technique, which combines suspension laryngoscopy with an operating microscope, microsurgical instruments, and a carbon dioxide laser (which is used because its frequency of light is absorbed by water, thus minimizing tissue damage). The tumor is transected, revealing the depth of invasion and allowing visualization of tumor margins, and removed piecemeal through the laryngoscope. At least one mobile arytenoid complex must be preserved so that function of the larynx is maintained.

If complete resection can be achieved, transoral laser surgery is often preferred over open partial laryngectomy in the treatment of early stage laryngeal cancer, given the accumulating evidence of comparable efficacy with decreased morbidity and improved preservation of laryngeal function.

Surgery versus RT: Early squamous cell carcinomas of the oropharynx can often be treated with either surgery or radiation therapy (RT) as a single modality. Definitive RT and primary surgery have yielded similar rates of local control and survival in retrospective studies, although there are no prospective randomized trials comparing the two approaches. The morbidity associated with each treatment approach is an important factor in making treatment decisions.(15)

RT is used more commonly, but surgery may be preferred in selected situations. Minimally invasive techniques such as transoral laser microsurgery (TLM) and transoral robotic surgery (TORS) have made resection of carefully selected early oropharyngeal cancers both feasible and well tolerated.

Radiation therapy: Primary RT may offer improved functional outcomes and a high chance for preservation of voice quality, while avoiding general anesthesia and other immediate risks associated with surgery. Most patients with T1-2 cancers are treated with single modality RT.

However, local recurrence following RT may require surgical salvage. Although some patients can be salvaged with larynx-preserving procedures, total laryngectomy is necessary in more than one-half of cases. In addition, surgical resection following RT has a higher risk of wound complications than similar surgery in the unirradiated neck. Radiation dermatitis, hoarseness, and painful or difficulty swallowing (odynophagia, dysphagia) commonly develop during the course of RT, but these acute toxicities typically resolve in two to eight weeks and are generally mild. Patients with early stage laryngeal cancer are less likely to have prolonged acute, subacute, and permanent toxicity than patients with advanced laryngeal cancer who require larger RT fields and concurrent chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy: Chemotherapy was also an option for the treatment of head and neck cancer patients. Chemotherapy alone does not have a role in the management of early stage laryngeal cancer outside of a clinical trial setting. Only uncommon and highly selected patients with T2 cancers (e.g. bulky, invasive T2 cancers with impaired cord mobility) may be appropriate for concurrent chemo radiation.

Adjuvant therapy: Stage I and II oropharyngeal cancers are most commonly managed initially with either RT or surgery.

- Patients with residual disease after primary RT are managed with salvage surgery.

- Patients initially treated with surgery should receive postoperative RT with or without concurrent chemotherapy for positive or close resection margins, extracapsular extension of lymph node disease, or other high risk features, such as lymphovascular and perineural invasion.(15)

Treatment protocols(16)

Treatment protocols for oral cavity, pharyngeal, and laryngeal cancers and for nasopharyngeal cancers are provided below, including generalized first-line therapy based on stage; chemoradiation therapy and induction chemotherapy for locally advanced disease; and first-, second-, and third-line chemotherapy for metastatic or recurrent disease.

Generalized treatment recommendations for oral cavity cancers

- Treatment plans for all disease stages should be discussed at a multidisciplinary tumor conference involving ENT surgeons, radiation oncologists, and medical oncologists

- Selected patients with advanced or metastatic disease may receive surgical resection of their primary tumors, depending on their response to first-line therapy.

Surgery or radiation therapy for early or localized oral cavity cancers

Stages I-II:

- Primary treatment for oropharyngeal cancers is surgical resection or definitive radiation therapy

- Surgery is the preferred approach except for some patients who may have early lip, retromolar trigone, and soft palate cancers

- Radiation therapy is preferred for patients who may not be able to tolerate surgery

- The radiation dose depends on tumor size; however, for early stage disease, doses of 66-74 Gy (2.0 Gy/fraction; daily Monday-Friday in 7wk

may be used with adequate results

Chemotherapy with radiation therapy for locally advanced oral cavity cancers

Stages III-IVB

- Surgery should be considered for locally advanced disease; however, definitive radiation therapy, concurrent chemoradiation, and induction therapy are alternative options for patients who are not candidates for surgery

- Concurrent chemoradiation therapy is the current standard of care for patients with locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck

- Chemotherapy is given for the duration of radiation therapy unless otherwise stated; definitive radiation doses used are 66-74 Gy (2.0 Gy/fraction; daily Monday-Friday in 7wk)

- Conventional fractionation for concurrent chemoradiation is ≥ 70 Gy (2.0 Gy/fraction)

- Postoperative radiation dose is 60-66 Gy (2.0 Gy/fraction); preferred interval between resection and postoperative radiation therapy is ≤ 6wk

- The decision to treat the patient with concurrent chemoradiation therapy rather than surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy individually should be made by a multidisciplinary tumor board (including a medical oncologist, a radiation therapist, and an ENT surgeon)

Acceptable chemotherapy regimens for primary systemic therapy with concurrent radiation:

- Cisplatin 100 mg/m2IV on days 1, 22, and 43or 40-50 mg/m2 IV weekly for 6-7wk or

- Cetuximab 400 mg/m2IV loading dose 1wk before the start of radiation therapy,then 250 mg/m2 weekly (premedicate with dexamethasone, diphenhydramine, and ranitidine) or

- Cisplatin 20 mg/m2IV on day 2 weekly for up to 7wkplus paclitaxel 30 mg/m2 IV on day 1 weekly for up to 7wk or

- Cisplatin 20 mg/m2/day IV on days 1-4 and 22-25plus 5-FU 1000 mg/m2/day by continuous IV infusion on days 1-4 and 22-25or

- 5-FU 800 mg/m2by continuous IV infusion on days 1-5 given on the days of radiationplus hydroxyurea 1 g PO q12h (11 doses per cycle); chemotherapy and radiation given every other week for a total of 13wk or

- Carboplatin 70 mg/m2/day IV on days 1-4, 22-25, and 43-46plus 5-FU 600 mg/m2/day by continuous IV infusion on days 1-4, 22-25, and 43-46 or

- Carboplatin AUC 1.5 IV on day 1 weeklyplus paclitaxel 45 mg/m2 IV on day 1 weekly.

Acceptable chemotherapy regimens for patients receiving postoperative concurrent chemoradiation:

Cisplatin 100 mg/m2 IV on days 1, 22, and 43 or 40-50 mg/m2 IV weekly for 6-7wk

Induction chemotherapy for locally advanced oral cavity cancers

Stages III-IVB:

- Induction chemotherapy is typically given to patients with stage III-IVB disease in order to shrink a primary tumor to reduce its bulkiness in preparation for future surgery or radiation therapy

- Decision to treat the patient with induction chemotherapy rather than concurrent chemoradiation or surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy alone should be made by a multidisciplinary tumor board (including a medical oncologist, a radiation therapist, and an ENT surgeon)

Acceptable chemotherapy regimens for induction chemotherapy:

- Docetaxel75 mg/m2IV on day 1 plus cisplatin 100 mg/m2 IV on day 1plus 5-FU 100 mg/m2/day by continuous IV infusion on days 1-4 every 3wk for 3 cycles; then 3-8wk later, carboplatin AUC 1.5 IV weekly for up to 7wk during radiation therapy; then 6-12wk later, pursue surgery if applicable or

- Docetaxel 75 mg/m2IV on day 1plus cisplatin 75 mg/m2 IV on day 1 plus 5-FU 750 mg/m2/day by continuous IV infusion on days 1-4 every 3wk for 4 cycles; then 4-7wk later, radiation; surgical resection can be pursued before or after chemotherapy

- Paclitaxel 175 mg/m2IV on day 1plus cisplatin 100 mg/m2 IV on day 2plus 5-FU 500 mg/m2/day by continuous IV infusion on days 2-6 every 3wk for 3 cycles; then radiation with cisplatin 100 mg/m2 IV on days 1, 22, and 43.

First-line chemotherapy for metastatic or recurrent oral cavity cancers

Stage IVC:

- Treatment recommendations include the use of single-agent or combination chemotherapy

- Platinum-based chemotherapy regimens are preferred if these agents can be tolerated by the patient; if they cannot be tolerated, single agents have been used in this setting

- Below are first-line chemotherapy options for metastatic disease or recurrent squamous head and neck cancers (after surgery and/or radiation)

Acceptable chemotherapy regimens in patients with metastatic (incurable) head and neck cancers (unless otherwise stated, goal is to complete at least 6 cycles):

- Cisplatin 100 mg/m2IV on day 1 every 3wk for 6 cyclesplus 5-FU 1000 mg/m2/day by continuous IV infusion on days 1-4 every 3wk for 6 cycles plus cetuximab 400 mg/m2 IV loading dose on day 1, then 250 mg/m2 IV weekly until disease progression (premedicate with dexamethasone, diphenhydramine, and ranitidine) or

- Carboplatin AUC 5 IV on day 1 every 3wk for 6 cyclesplus 5-FU 1000 mg/m2/day by continuous IV infusion on days 1-4 every 3wk for 6 cycles plus cetuximab 400 mg/m2 IV loading dose on day 1, then 250 mg/m2 IV weekly until disease progression (premedicate with dexamethasone, diphenhydramine, and ranitidine) or

- Cisplatin 75 mg/m2IV on day 1plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 IV on day 1 every 3wk or

- Cisplatin 75 mg/m2IV on day 1plus paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 IV on day 1 every 3wk or

- Carboplatin AUC 6 IV on day 1plus docetaxel 65 mg/m2 IV on day 1 every 3wk or

- Carboplatin AUC 6 IV on day 1plus paclitaxel 200 mg/m2 IV on day 1 every 3wk or

- Cisplatin 75-100 mg/m2IV on day 1 every 3-4wkplus cetuximab 400 mg/m2IV loading dose on day 1, then 250 mg/m2 IV weekly (premedicate with dexamethasone, diphenhydramine, and ranitidine) or

- Cisplatin 100 mg/m2IV on day 1plus 5-FU 1000 mg/m2/day by continuous IV infusion on days 1-4 every 3wk or

- Methotrexate40 mg/m2IV weekly (3wk equals 1 cycle) or

- Paclitaxel 200 mg/m2IV every 3wkor

- Docetaxel 75 mg/m2IV every 3wkor

- Cetuximab 400 mg/m2IV loading dose on day 1,then 250 mg/m2 IV weekly until disease progression (premedicate with dexamethasone, diphenhydramine, and ranitidine)

Second- and third-line chemotherapy for metastatic or recurrent oral cavity cancers

Stage IVC:

- Second-line chemotherapy is given after disease progression or recurrence following completion of first-line therapy

- Third-line therapies are given after disease progression or recurrence following completion of first-line and second-line therapies

- Second- and third-line regimens are similar to regimens used as first-line therapy but usually offer lower response rates and survival benefits

- Patients should be treated with platinum-based chemotherapy regimens if they have not previously received a platinum-based drug.

Acceptable chemotherapy regimens in patients with recurrent head and neck cancers (unless otherwise stated, goal is to complete at least 6 cycles):

- Cisplatin 100 mg/m2IV on day 1 every 3wk for 6 cyclesplus 5-FU 1000 mg/m2/day by continuous IV infusion on days 1-4 every 3wk for 6 cycles plus cetuximab 400 mg/m2 IV loading dose on day 1, then 250 mg/m2 IV weekly until disease progression (premedicate with dexamethasone, diphenhydramine, and ranitidine) or

- Carboplatin AUC 5 IV on day 1 every 3wk for 6 cyclesplus 5-FU 1000 mg/m2/day by continuous IV infusion on days 1-4 every 3wk for 6 cycles plus cetuximab 400 mg/m2 IV loading dose on day 1, then 250 mg/m2 IV weekly until disease progression (premedicate with dexamethasone, diphenhydramine, and ranitidine) or

- Cisplatin 75 mg/m2IV on day 1plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 IV on day 1 every 3wk or

- Cisplatin 75 mg/m2IV on day 1plus paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 IV on day 1 every 3wk or

- Carboplatin AUC 6 IV on day 1plus docetaxel 65 mg/m2 IV on day 1 every 3wk or

- Carboplatin AUC 6 IV on day 1plus paclitaxel 200 mg/m2 IV on day 1 every 3wk or

- Cisplatin 75-100 mg/m2IV on day 1 every 3-4wkplus cetuximab 400 mg/m2IV loading dose on day 1, then 250 mg/m2 IV weekly (premedicate with dexamethasone, diphenhydramine, and ranitidine) or

- Cisplatin 100 mg/m2IV on day 1plus 5-FU 1000 mg/m2/day by continuous IV infusion on days 1-4 every 3wk or

- Methotrexate 40 mg/m2IV weekly (3wk equals 1 cycle) or

- Paclitaxel 200 mg/m2IV every 3wkor

- Docetaxel 75 mg/m2IV every 3wk or

- Cetuximab 400 mg/m2IV loading dose on day 1,then 250 mg/m2 IV weekly until disease progression (premedicate with dexamethasone, diphenhydramine, and ranitidine)

Generalized treatment recommendations for nasopharyngeal cancers

- Treatment plans for all disease stages should be discussed at a multidisciplinary tumor conference involving ENT surgeons, radiation oncologists, and medical oncologists

- Selected patients with advanced or metastatic disease may receive additional therapy (radiation or neck dissection) depending on their response to first-line therapy Surgery at the primary disease site has a very limited role, if any, in nasopharyngeal cancers

Radiation therapy for early or localized disease (nasopharyngeal cancers)

Stage I:

- Patients with early or localized disease may be treated with definitive radiation therapy to the nasopharynx alone

- Radiation doses of 66-70 Gy (2.0 Gy/fraction; daily Monday-Friday in 7wk)

Chemotherapy with radiation therapy for locally advanced nasopharyngeal Cancers

Stages II-IVB:

- Patients with stage II-IVB nasopharyngeal cancers are treated with concurrent chemotherapy and radiation +/- adjuvant chemotherapy or with induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiation

Acceptable chemotherapy regimen for advanced nasopharyngeal cancers (stages II-IVB):

- Cisplatin 100 mg/m2IV on days 1, 22, and 43 with radiation, then cisplatin 80 mg/m2IV on day 1 plus 5-FU 1000 mg/m2/day by continuous IV infusion on days 1-4 every 4wk for 3 cycles or

- Carboplatin AUC 6 IV every 3 weeks for 3 cycles with radiation +/- adjuvant chemotherapy with carboplatin AUC 5 IV on day 1 plus fluorouracil (5-FU) 1000 mg/m2/day by continuous IV infusion on days 1-4 every 3 weeks for 2 cycles

- Radiation doses during concurrent chemoradiation are 70 Gy (2.0 Gy/fraction)

- Induction chemotherapy with docetaxel 70 mg/m2 IV on day 1 plus cisplatin 75 mg/m2 IV on day 1 plus 5-FU 1000 mg/m2/day by continuous IV infusion on days 1-4 for three cycles followed by concurrent chemoradiation with cisplatin 100 mg/m2 IV on days 1, 22, and 43.

First-line chemotherapy for metastatic or recurrent nasopharyngeal cancers

Stage IVC:

- Patients with metastatic nasopharyngeal cancers or recurrent disease (after first-line therapy) are treated with standard platinum-based chemotherapies

- Single agents can be used if patients cannot tolerate platinum-based agents

Acceptable chemotherapy regimens in patients with progressing or recurrent nasopharyngeal cancers (unless otherwise stated, goal is to complete 4-6 cycles):

- Cisplatin 75 mg/m2IV on day 1plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 IV on day 1 every 3wk or

- Cisplatin 75 mg/m2IV on day 1plus paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 IV on day 1 every 3wk or

- Carboplatin AUC 6 IV on day 1plus docetaxel 65 mg/m2 IV on day 1 every 3wk or

- Carboplatin AUC 6 IV on day 1plus paclitaxel 200 mg/m2 IV on day 1 every 3wk or

- Cisplatin 100 mg/m2IV on day 1plus 5-FU 1000 mg/m2/day by continuous IV infusion on days 1-4 every 3wk or

- Cisplatin 50-70 mg/m2IV on day 1plus gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 IV on days 1, 8, and 15 every 4wk or

- Cetuximab 400 mg/m2 IV on day 1 followed by 250 mg/m2 IV weekly plus carboplatin AUC 5 IV every 3 weeks for up to 8 cycles or

- Gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2IV on days 1, 8, and 15 every 4wkor

- Gemcitabine 1250 mg/m2IV on days 1 and 8 every 3wkor

- Methotrexate 40 mg/m2IV weekly (3wk equals 1 cycle)or

- Paclitaxel 200 mg/m2IV every 3wkor

- Docetaxel 75 mg/m2 IV every 3wkor

Second- and third-line chemotherapy for metastatic or recurrent nasopharyngeal cancers

Stage IVC:

- Second-line chemotherapy is given after disease progression or recurrence following completion of first-line therapy

- Third-line therapies are given after disease progression or recurrence following completion of first- and second-line therapies

- Second- and third-line regimens are similar to regimens used as first-line therapy but usually offer lower response rates and survival benefits

- Patients should be treated with platinum-based chemotherapies if they have not previously received a platinum-based drug

- Some regimens are typically used in head and neck cancers in general, and others have been specifically studied in nasopharyngeal cancer

Acceptable chemotherapy regimens in patients with progressing or recurrent nasopharyngeal cancers after completion of first-line therapy:

- Cisplatin 75 mg/m2IV on day 1plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 IV on day 1 every 3wk or

- Cisplatin 75 mg/m2IV on day 1plus paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 IV on day 1 every 3wkor

- Carboplatin AUC 6 IV on day 1plus docetaxel 65 mg/m2 IV on day 1 every 3wk or

- Carboplatin AUC 6 IV on day 1plus paclitaxel 200 mg/m2 IV on day 1 every 3wkor

- Cisplatin 100 mg/m2IV on day 1plus 5-FU 1000 mg/m2/day by continuous IV infusion on days 1-4 every 3wk or

- Cisplatin 50-70 mg/m2IV on day 1plus gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 IV on days 1, 8, and 15 every 4wkor

- Gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2IV on days 1, 8, and 15 every 4wkor gemcitabine 1250 mg/m2 IV on days 1 and 8 every 3wk or

- Methotrexate 40 mg/m2IV weekly (3wk equals 1 cycle)or

- Paclitaxel 200 mg/m2IV every 3wkor

- Docetaxel 75 mg/m2IV every 3wk

GOALS OF THERAPY

Many cancers of the head and neck can be cured, especially if they are found early. Although eliminating the cancer is the primary goal of treatment, preserving the function of the nearby nerves, organs, and tissues is also very important. When planning treatment, doctors consider how treatment might affect a person’s quality of life, such as how a person feels, looks, talks, eats, and breathes.

GUIDELINES

To view, “ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines: Head and Neck Cancers”, please click on below link:

https://www.esmo.org/Guidelines/Head-and-Neck-Cancers

To view, “NCCN Guidelines Insights: Head and Neck Cancers, Version 1.2018”, please click on below link:

www.jnccn.org/content/16/5/479.full

CONSULTATION AND LONG TERM MONITORING

Regular post-treatment follow-up is an essential part of the care of patients after potentially curative treatment of head and neck cancer. Patients should be educated about the possible signs and symptoms of a second primary cancer and locoregional recurrence, including hoarseness, pain, dysphagia, bleeding, and enlarged lymph nodes. Consistent with the standards of the Commission on Cancer for those treated with curative intent, a survivorship care plan and treatment summary should be generated and reviewed in detail with the patient within six months of completion of therapy, and a copy should be shared with the patient and primary care physician.

- Upon completion of therapy, post-treatment imaging is important to evaluate for residual disease and establish a baseline. Best approach is to conduct a clinical evaluation around six weeks following RT or chemoradiotherapy and then a complete evaluation, including imaging (CT or MRI and generally a PET/CT) at 12 weeks to document regression of the primary tumor. Imaging should not be performed too soon. Obtaining imaging studies, particularly PET/CT, prior to 12 weeks following treatment can lead to an increased frequency of false positive results. CT or MRI can be carried out at four to six weeks if needed as part of the clinical evaluation.

- For patients who have clinically involved cervical lymph node disease prior to RT or chemoradiotherapy, functional imaging (PET) and structural imaging (CT/MRI) are important components of assessment of response to initial therapy.

- Following treatment, the intensity of follow-up is greatest in the first two to four years. Approximately 80 to 90 percent of all recurrences occur during this time-frame; the risk of a second primary malignancy is higher than the recurrence risk for most patients after three years.

- However, lifetime follow-up is generally suggested since the morbidity of treatment can worsen over time, and the risk of recurrence and second primary malignancy remains elevated beyond the first five years, especially for cancers of the hypopharynx, larynx, nasopharynx, and salivary glands. Because of the higher risk of recurrence and second primary malignancy, as well as other late toxicities, in those who continue tobacco use, many schedule more frequent surveillance visits for these patients and continue for a longer duration (i.e. beyond five years).

Rehabilitation or support options for head and neck cancer’s patient

- Depending on the location of the cancer and the type of treatment, rehabilitation may include physical therapy, dietary counseling, speech therapy, and/or learning how to care for a stoma.

- Sometimes, especially with cancer of the oral cavity, a patient may need reconstructive and plastic surgery to rebuild bones or tissues. If reconstructive surgery is not possible, a prosthodontist may be able to make a prosthesis(an artificial dental and/or facial part) to restore satisfactory swallowing, speech, and appearance.

- Patients who have trouble speaking after treatment may need speech exercises or alternative methods of speaking.

- Eating may be difficult after treatment for head and neck cancer. A feeding tube is a flexible plastic tube that is passed into the stomach through the nose or an incision in the abdomen.

PRECAUTIONS

Provide following precautions to patients:

- Avoid oral HPV infection may reduce the risk of HPV-associated head and neck cancers. Reduce risk of HPV infection by giving the HPV vaccine.

- Stopping the use of all tobacco products is the most important thing a person can do to reduce their risk, even for people who have been smoking for many years.

- Avoid alcohol

- Avoid marijuana use

- Use sunscreen regularly, including lip balm with an adequate sun protection factor (SPF)

- Limit number of sexual partners, since having many partners increases the risk of HPV infection.

- Use a condom during sex cannot fully protect you from HPV.

Maintaining proper care of dentures. Poorly fitting dentures can trap tobacco and alcohol’s cancer-causing substances. People who wear dentures should have their dentures evaluated by a dentist at least every 5 years to ensure a good fit. Dentures should be removed every night and cleaned and rinsed thoroughly every day.

REFERENCES

- Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011; 61:69.

- Bray F, Ren JS, Masuyer E, Ferlay J. Global estimates of cancer prevalence for 27 sites in the adult population in 2008. Int J Cancer 2013; 132:1133./Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 2016; 66:7.

- Lambert R, Sauvaget C, de Camargo Cancela M, Sankaranarayanan R. Epidemiology of cancer from the oral cavity and oropharynx. Eur J GastroenterolHepatol 2011; 23:633.

- Akhtar A, et al. Prevalence and diagnostic of head and neck cancer in Pakistan. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2016 Sep;29(5 Suppl):1839-1846.

- Gatta G, Botta L, Sanchez MJ, et al. Prognoses and improvement for head and neck cancers diagnosed in Europe in early 2000s: The EUROCARE-5 population-based study. Eur J Cancer 2015; 51:2130./DeSantis C, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 2013; 63:151.

- National cancer institute. Head and Neck Cancers [internet]. Bethesda: National cancer institute [cited 2019 Jan 18] Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/types/head-and-neck/head-neck-fact-sheet#q1

- John Andrew et al. Head and Neck Tumors. Available from: http://www.cancernetwork.com/cancer-management/head-and-neck-tumors/page/0/1 (Accessed on 2019 Jan 22)

- Cancer.Net. Head and Neck Cancer: Symptoms and Signs [internet]. Alexandria : Cancer.net [cited 2019 Jan 11] Available from: https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/head-and-neck-cancer/symptoms-and-signs

- BC cancer. Head and neck. Available from: http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/health-professionals/clinical-resources/cancer-management-guidelines/head-neck/head-neck#diagnosis (Accessed on 2019 Jan 22)

- Tandon S, Shahab R, Benton JI, et al. Fine-needle aspiration cytology in a regional head and neck cancer center: comparison with a systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck 2008; 30:1246.

- Weissman JL, Akindele R. Current imaging techniques for head and neck tumors. Oncology (Williston Park) 1999; 13:697.

- Sakata K, Hareyama M, Tamakawa M, et al. Prognostic factors of nasopharynx tumors investigated by MR imaging and the value of MR imaging in the newly published TNM staging. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1999; 43:273.

- Rasch C, Keus R, Pameijer FA, et al. The potential impact of CT-MRI matching on tumor volume delineation in advanced head and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1997; 39:841.

- Loh KS, Brown DH, Baker JT, et al. A rational approach to pulmonary screening in newly diagnosed head and neck cancer. Head Neck 2005; 27:990.

- Koch MW, Machtay M, Best S. Treatment of early (stage I and II) head and neck cancer: The larynx [internet]. Waltham, Massachusetts: UptoDate [cited 2019 Jan 11] Available from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-early-stage-i-and-ii-head-and-neck-cancer-the-larynx

- Stevenson MM. Head and Neck Cancer Treatment Protocols [Internet]. New York: Medscape [updated: 2016 Feb 29; cited 2019 Jan 11] Available from http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2006216-overview