The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that hepatitis E virus (HEV) causes 20 million new infections annually, with more than 3 million cases of acute hepatitis and over 55,000 deaths.(1) HEV infection has a global distribution.(2-16) Specific genotypes result in infection in different geographic areas.

- Genotypes 1 and 2 have been reported mainly in Asia, India, and North Africa.

- Genotype 2 has been identified in Mexico and West Africa.

- Genotype 3 is prevalent in Western countries, as well as in Asia and North America.

Genotype 4 has been detected in Asian and European countries.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Hepatitis E is an enterically transmitted infection that is typically self-limited.(17,18) It is caused by the hepatitis E virus (HEV) and is spread by fecally contaminated water within endemic areas or through the consumption of uncooked or undercooked meat.

HEV has an incubation period of 2-10 weeks.(1) Acute HEV infection is generally less severe than acute HBV infection and is characterized by fluctuating aminotransferase levels. However, pregnant women, especially when infected during the third trimester, have a greater than 25% risk of mortality associated with acute HEV infection.(19)

Traditionally, HEV was not believed to cause chronic liver disease. However, several reports have described chronic hepatitis due to HEV in organ transplant recipients. Liver histology revealed dense lymphocytic portal infiltrates with interface hepatitis, similar to the findings seen with hepatitis C infection. Some cases have progressed to cirrhosis.(20,21)

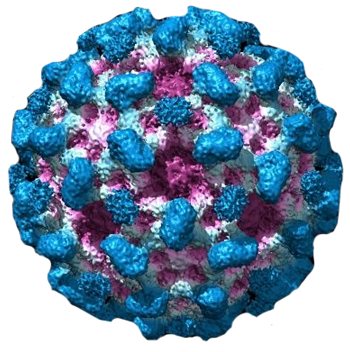

The hepatitis E virus (HEV) genome contains 3 open reading frames (ORFs). The largest, ORF-1, codes for the nonstructural proteins responsible for viral replication. ORF-2 contains genes encoding the capsid. The function of ORF-3 is unknown, but the antibodies directed against ORF-3 epitopes have been identified.

Five HEV genotypes have been identified. Genotypes 1 and 2 are considered human viruses; genotypes 3 and 4 are zoonotic and have been isolated from humans and animals (e.g. pigs, boars, deer), and genotype 7 primarily infects dromedaries.(22,23)

TRANSMISSION

Transmission of hepatitis E virus (HEV) can occur through contaminated food and water, blood transfusions, and through mother-to-child transmission. Although person-to-person transmission is uncommon, patients are infectious during fecal shedding. Specific genotypes differ in their route of transmission.

Contaminated food and water

- Waterborne infection: HEV genotype 1 and 2 infections are spread by fecally contaminated water in endemic areas.(24,25) Thus, in resource-limited countries where sanitation and water purification services are limited, there is a high rate of lifetime exposure to HEV associated with HEV genotype 1 and 2 (and possibly 4) infection.

- Zoonotic transmission: HEV genotypes 3 and 4 usually cause infections due to consumption of contaminated food. Most cases are sporadic and unidentified as an acute viral hepatitis, although isolated outbreaks have occurred, including an HEV outbreak associated with consumption of shellfish that affected passengers on a cruise ship.(26)

Swine are most frequently implicated in transmission, followed by consumption of filter feeder shellfish.(27-30) However, many animal species (including rodents in some regions), have been identified as part of the viral reservoir of disease.(31)

There are limited data regarding food preparation to reduce/eliminate HEV transmission. In one study, cooking liver at 191°F for five minutes or boiling liver for five minutes reduced the risk of transmission by inactivating HEV.(32)

Blood transfusion:

HEV can be transmitted by blood transfusions, particularly in endemic areas.(33-36) In one study that evaluated the prevalence and transmission of HEV in 225,000 blood donations, 79 HEV genotype 3 RNA-positive donations were detected.(36) These donations were used to prepare 129 blood components and 62 were transfused. On follow-up testing of 43 recipients, 18 (42 percent) HEV infections were detected.

Perinatal transmission:

There are limited data regarding vertical transmission of HEV from infected mothers to their infants. Case series suggest that HEV infection can be transmitted from mother to newborn with substantial perinatal morbidity and mortality; however, its contribution to the overall disease burden appears to be small.(37-39)

Transmission in breast milk:

It is unclear if breastfeeding is a potential route of HEV transmission. However, there is sufficient concern to discourage breastfeeding among confirmed HEV-infected mothers until further data are available. In one case report, HEV was isolated in breast milk during the acute phase of HEV infection.(40) Milk and serum HEV titers were comparable.

NATURAL HISTORY

In an acute infection the incubation period ranges from 15 to 60 days, through which viremia arises. Anti-HEV antibody (IgM) appears soon after the onset of the clinical infection. Anti-HEV IgG appears soon after that and can remain detectable for as long as 20 months (Figure 1). HEV RNA is detected in stool as early as 1 week before the onset of clinical illness and persists for 1 to 2 weeks afterward, during which stools are highly infectious.(41)

Similar to hepatitis A, HEV is most often a self-limited disease; immunity develops, and no second attack occurs. The disease is often cholestatic, with elevated bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels. On average, it occurs more commonly in the older population and severe disease, including fulminant hepatitis and death, occur more often in HEV than in other types of hepatitis.(42) Mortality rates range from 0% to 10%, but it is usually less than 1%. In pregnant women, infection has been associated with development fulminant liver failure and mortality can reach 25%.(43,44)

SIGN AND SYMPTOMS

Acute Hepatitis E:

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) generally causes a self-limited acute infection, although acute hepatic failure can develop in a small proportion of patients.

Clinical features: The vast majority of patients with acute HEV are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic.(45) The proportion of people who develop clinical features following acute infection varies based upon age and prior HEV exposure.(46)

In symptomatic patients, jaundice is usually accompanied by malaise, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, fever, and hepatomegaly.(47) Other less common features include diarrhea, arthralgia, pruritus, and urticarial rash.(48-51)

In addition, patients occasionally have extrahepatic findings. These include:(52)

- Hematologic abnormalities including thrombocytopenia, hemolysis, and aplastic anaemia

- Acute thyroiditis

- Membranous glomerulonephritis

- Acute pancreatitis

- Neurological diseases including:

- Acute transverse myelitis

- Acute meningoencephalitis

- Aseptic meningitis

- Neuralgic amyotrophy

- Pseudotumor cerebri

- Bilateral pyramidal syndrome

- Guillain–Barré syndrome

- Cranial nerve palsies

- Peripheral neuropathy

Laboratory findings: Laboratory findings include elevated serum concentrations of bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and aspartate aminotransferase.(48,53) Symptoms coincide with a sharp rise in serum ALT levels, which may rise up into the thousands and return to normal during convalescence.(54) Resolution of the abnormal biochemical tests generally occurs within one to six weeks after the onset of the illness (figure 1).

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection typical serologic course (courtesy Uptodate)

ALT: alanine aminotransferase; IgG: immunoglobulin G.

Liver histology: Morphological features of HEV include those noted with cholestatic and classic types of acute viral hepatitis. Cholestatic forms are characterized by bile stasis in canaliculi and gland-like transformation of hepatocytes. Other histologic findings include focal necrosis, ballooned hepatocytes, and acidophilic degeneration of hepatocytes.(55,56) In fatal cases, submassive or massive hepatic necrosis is present.(3,49)

In immunosuppressed patients, development of chronic hepatitis leads to inflammation and progressive fibrosis, which can lead to cirrhosis. In patients who have undergone organ transplantation, this process may be mistaken for rejection.(57)

Complications: The majority of patients who acquire HEV spontaneously clear the virus. However, patients may develop complications such as acute hepatic failure, cholestatic hepatitis, or chronic HEV.

- Acute hepatic failure: A small proportion (0.5 to 4 percent) of HEV-infected persons develop acute hepatic failure.(58) As an example, in the United States Acute Liver Failure Study, only 3 of 681 adults demonstrated anti-HEV IgM antibodies, but none were HEV RNA positive, indicating that acute HEV is not a common cause of acute hepatic failure in the United States.(59) When it does occur, acute hepatic failure is more likely in those who are pregnant and in those who are malnourished or have preexisting liver disease.

Acute hepatic failure is characterized by hepatic encephalopathy, elevated aminotransferases (often with abnormal bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels), and impaired synthetic function (international normalized ratio ≥1.5). Acute hepatic failure carries a high mortality if intensive care support and liver transplantation are not available, resulting in an overall case fatality rate of 0.5 to 3 percent.(60)

- Cholestatic hepatitis: Prolonged cholestasis, characterized by a protracted period of jaundice (lasting >3 months), has been described in up to 60 percent of patients with acute HEV.(61) Patients may be asymptomatic or have symptoms of pruritus due to cholestasis. In general, cholestatic hepatitis resolves spontaneously within weeks to months with no sequelae.(62) Recovery is marked by viral clearance, an increase in IgG anti-HEV titers, and a decrease in IgM anti-HEV levels.(63)

- Chronic hepatitis E: Chronic HEV infection is defined empirically as detection of HEV RNA in serum or stool for longer than six months. Chronic HEV almost exclusively occurs in immunosuppressed patients (e.g. those with HIV infection, following solid organ or bone marrow transplantation).(64-67) Chronic infection is typically with HEV genotype 3 infection, although chronic infection with genotype 4 has been documented in a transplant recipient.(68,69) Chronic HEV infection with genotypes 1 and 2 have not been reported.

As with most chronic viral hepatitis patients, symptoms are minimal and include fatigue and nonspecific findings until progression to decompensated cirrhosis occurs. Patients with chronic HEV have persistently elevated aminotransferase levels, detectable serum HEV RNA, and histologic findings compatible with chronic viral hepatitis.

SCREENING

According to EASL 2018 guidelines on hepatitis E, several countries have introduced universal, targeted or partial screening for HEV in donors, including Ireland, the UK, France, the Netherlands and Japan. In Germany, some blood transfusion companies have introduced voluntary HEV screening. In many other countries donor screening is being considered.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

General approach:

The diagnosis of hepatitis E virus (HEV) should be considered in patients who present with acute or chronic hepatitis that cannot be explained by other causes. This includes putative cases of drug-induced liver injury which have been misclassified because HEV testing was not performed. It is particularly important that the diagnosis of HEV infection be considered in groups that are at risk for developing rapidly progressive liver disease, such as pregnant women, patients with underlying liver disease, solid organ transplant recipients, and those with hematologic malignancies.(71)

- Acute HEV: The diagnosis of acute HEV is complicated by the lack of a standardized assay. Multiple commercial enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kits have been developed and have high variability in terms of test performance; both false positives and negatives are common with available assays.

- In general, the initial test method is an anti-HEV IgM assay. The presence of IgM anti-HEV antibodies is suggestive of recent HEV infection.

- If the initial test is positive, confirmatory testing should be performed when available since no single EIA method achieves high specificity. Confirmatory testing may include an alternate anti-HEV IgM, evidence of rising anti-HEV IgG titers (greater than fivefold change over two weeks), or detection of HEV RNA in serum or stool.(72)

- If initial EIA testing is negative, and there is still a high suspicion for HEV infection, repeat testing should be performed, preferably with an HEV RNA assay. The use of RNA testing is particularly important in immunocompromised hosts with suspected HEV due to a high rate of false-negative antibody testing.(54,73,74)

- Chronic HEV: In patients with suspected chronic HEV infection, detection of HEV RNA in serum is the mainstay of diagnosis. Chronic HEV infection is defined as detection of HEV RNA in serum or stool for longer than six months.

Testing for IgG anti-HEV antibodies is of limited utility in the diagnosis of chronic HEV infection. The presence of IgG (or total) anti-HEV antibodies is a marker of exposure to HEV, which can be either recent or remote. In addition, the decline in IgG anti-HEV titers with time might adversely affect its sensitivity for detecting remote infection (figure 1).

Diagnostic tests:

Antibody testing: The timing of appearance of HEV markers is important for interpreting results of serologic testing in the setting of acute hepatitis (figure 1).

- IgM anti-HEV appears during the early phase of clinical illness and disappears rapidly over four to five months (figure 1).(53) Although IgM anti-HEV has been detected in the serum by EIA in more than 90 percent of patients in some outbreak settings when samples were obtained within one week to two months after the onset of illness, serology may be negative in a substantial proportion of patients with acute infection.(75)

- The IgG response appears shortly after the IgM response, and its titer increases throughout the acute phase into the convalescent phase. It is unclear how long IgG anti-HEV antibodies persist. In one report, antibodies were detected as long as 14 years after the acute phase of illness; however, a booster effect due to reinfection could not be excluded.(53,76-79)

HEV RNA assay: HEV can be detected in stool approximately one week before the onset of illness and can persist for as long as two weeks thereafter.(2,80-82) In serum, HEV may be detected two to six weeks after infection and can persist for two to four weeks in those who resolve acute infection. Although HEV viremia is short-lived in most patients with acute infection, it can persist for years in those who develop chronic infection (figure 1).(83,84)

Imaging Studies

Abdominal radiography has no role in evaluating acute viral hepatitis unless clinically indicated.

Abdominal ultrasonography is recommended. It helps to rule out extra hepatic causes of biliary obstruction, which may coexist with the presence of hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection. It may also demonstrate the presence of an enlarged liver and the presence of advanced liver disease, such as splenomegaly, ascites, or hepatofugal flow of the portal venous system.

Basic Laboratory Studies

Elevation in the serum aminotransferase levels is the laboratory hallmark of acute viral hepatitis. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level is usually higher than the serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level. The levels of aminotransferases may range from 10 times the upper limit of normal to more than 20 times the upper limit of normal. They increase rapidly and peak within 4-6 weeks of onset but generally return to normal within 1-2 months after the peak severity of the disease has passed. The serum alkaline phosphatase level may be normal or slightly increased (<3 times upper limit of normal). Serum bilirubin level usually ranges from 5-20 mg/dL, depending on the extent of hepatocyte damage. The patient may develop leukopenia with neutropenia or lymphopenia. Prolonged prothrombin time, decreased serum albumin, and very high bilirubin are signs of impending hepatic failure requiring referral to a liver transplantation center.

Perform blood cultures if the patient is febrile and hypotensive with an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count.

Obtain serum acetaminophen levels if overdose is suspected.

Tissue Analysis and Histologic Findings

Liver biopsy usually is not necessary.

Biopsies from acute fulminant hepatitis E show varying degrees of hepatocyte necrosis and mixed portal and lobular inflammation, accompanied by bile ductular proliferation, lymphocytic cholangitis, Kupffer cell prominence, cholestasis, apoptotic bodies, pseudo-rosette formation, steatosis, and plasma cells in the portal tracts.

Compared with the epidemic type of acute hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection, liver biopsy from patients with autochthonous HEV infection show preferential localization of polymorphs at the portal-hepatocyte interface, and that of lymphocytes and plasma cells centrally in portal tracts. Hepatocyte necrosis is reported to be located in the perivenular acinar zone 3 in patients with autochthonous HEV infection. The histology of epidemic cases of HEV infection show less intense portal and acinar inflammation, no cholangiolitis, and no geographical distribution of the portal inflammatory infiltrate. Significant steatosis, megamitochondria, and Mallory bodies are not present in autochthonous cases.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Management of hepatitis E virus (HEV) depends upon the immune status of the patient and the stage of disease (e.g. acute versus chronic).

Acute hepatitis E:

For most patients, the management of acute HEV infection is supportive, as the disease appears to be mild and self-limited in immunocompetent patients. However, patients with acute HEV infection who develop fulminant hepatic failure may require liver transplantation.(85)

The role of antiviral therapy in immunocompromised patients with acute HEV has not been established. Ribavirin should not be used in pregnant women as it is a potent teratogen. In addition, although small retrospective studies have suggested that patients with chronic liver disease and those receiving immunosuppressive therapy may benefit from ribavirin monotherapy,(86-92) it is unclear if improvement was spontaneous or due to ribavirin in the absence of controls.

Chronic hepatitis E:

Chronic HEV occurs almost exclusively in immunocompromised patients.

The management of chronic infection involves reduction of immunosuppressive therapy and/or antiviral therapy.

Reduction of immunosuppression: A reduction in immunosuppressive therapy is the first step in the treatment of chronic HEV infection. There are no clear data to guide how immunosuppressive therapy should be reduced; however, for solid organ transplant recipients, typically reduce tacrolimus first, if possible, since there is an association of chronic infection with tacrolimus.

Clearance of chronic HEV infection has been reported after reducing or withdrawing immunosuppressive therapy.(93,94) As an example, in a retrospective series that evaluated 85 solid organ transplant recipients with chronic HEV, reduction of immunosuppressive therapy resulted in viral clearance in approximately 30 percent of patients.(93)

Antiviral therapy: Antiviral therapy is directed against genotype 3, since chronic infection is typically observed in patients with this genotype.(95)

Whom to treat: 12-week course of ribavirin monotherapy is recommended to certain nonpregnant patients with chronic HEV infection.(54)

- In solid organ transplant recipients, ribavirin is administered in conjunction with reducing immunosuppressive therapy.

- For others, antiviral therapy is administered if immunosuppressive therapy cannot be reduced, or if the patient has persistent HEV RNA despite a reduction in immunosuppressive therapy for 12 weeks.(85,95)

The dose of ribavirin is 600 to 1000 mg daily (administered in two divided doses).

Treatment failure: Patients who fail to achieve an SVR should continue to be followed for signs of progression of liver disease. There is no established alternative antiviral therapy with evidence of efficacy in this setting.

Therapies that have been considered for the management of treatment failure include pegylated interferon-alfa and sofosbuvir. However, concerns regarding toxicity and efficacy prevent these agents from being used in routine care.

GOAL OF THERAPY

The goal of treatment is to eradicate HEV RNA, which is predicted by achieving a sustained virologic response (SVR). An SVR is defined as the absence of HEV RNA by polymerase chain reaction 12 weeks after cessation of treatment. Patients with an SVR are considered cured since there is no viral reservoir, similar to hepatitis C virus; however, they remain at risk for reinfection.

GUIDELINES

To view, EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on hepatitis E virus infection 2018, please click on below link:

https://www.journal-of-hepatology.eu/article/S0168-8278(18)30155-7/pdf

To view WHO guidance on Waterborne Outbreaks of Hepatitis E: recognition, investigation and control, please click on below link:

http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/hepatitis/HepE-manual/en/

To view British Transplantation Society (BTS) draft Guidelines for Hepatitis E & Solid Organ Transplantation, please click on below link:

https://bts.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/BTS-HEV-Guideline-CONSULTATION_DRAFT.pdf

CONSULTATION AND COUNCELLING

The acute illness may result in anorexia, nausea, and vomiting, predisposing patients to dehydration. These symptoms tend to be worse in the afternoon or evening. Patients should attempt to ingest significant calories in the morning. As they improve, frequent small meals may be better tolerated. Hospitalization should be considered for patients with dehydration. Neither multivitamins nor specific dietary requirements are required.

Patients should be allowed to function at whatever activity levels they can tolerate. No evidence indicates that bed rest hastens recovery. It actually may retard recovery.

PREVENTION

General measures: Management should be predominantly preventive, relying on clean drinking water, good sanitation, and proper personal hygiene. Travelers to regions where hepatitis E virus (HEV) is endemic should follow the general precautions used for the prevention of travelers’ diarrhea. This includes avoidance of water of unknown purity, food from street vendors, raw or undercooked seafood, meat or pork products, and raw vegetables.

Vaccines – Recombinant vaccines have demonstrated efficacy against HEV.

Immune globulin: The efficacy of pre- or post-exposure immune globulin prophylaxis for the prevention of HEV has not been established.

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization. Hepatitis E Fact sheet (updated July 2016). http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs280/en/ (Accessed on November 28, 2018).

- Balayan MS, Andjaparidze AG, Savinskaya SS, et al. Evidence for a virus in non-A, non-B hepatitis transmitted via the fecal-oral route. Intervirology 1983; 20:23

- Khuroo MS. Study of an epidemic of non-A, non-B hepatitis. Possibility of another human hepatitis virus distinct from post-transfusion non-A, non-B type. Am J Med 1980; 68:818.

- Meng XJ, Wiseman B, Elvinger F, et al. Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis E virus in veterinarians working with swine and in normal blood donors in the United States and other countries. J Clin Microbiol 2002; 40:117.

- Thomas DL, Yarbough PO, Vlahov D, et al. Seroreactivity to hepatitis E virus in areas where the disease is not endemic. J Clin Microbiol 1997; 35:1244.

- Kuniholm MH, Purcell RH, McQuillan GM, et al. Epidemiology of hepatitis E virus in the United States: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. J Infect Dis 2009; 200:48.

- Tang YW, Wang JX, Xu ZY, et al. A serologically confirmed, case-control study, of a large outbreak of hepatitis A in China, associated with consumption of clams. Epidemiol Infect 1991; 107:651.

- Quintana A, Sanchez L, Larralde O, Anderson D. Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis E virus in residents of a district in Havana, Cuba. J Med Virol 2005; 76:69.

- Lynch M, O’Flynn N, Cryan B, et al. Hepatitis E in Ireland. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1995; 14:1109.

- Sylvan SP. The high rate of antibodies to hepatitis E virus in young, intravenous drug-abusers with acute hepatitis B-virus infection in a Swedish community: a study of hepatitis markers in individuals with intravenously or sexually acquired hepatitis B-virus infection. Scand J Infect Dis 1998; 30:429.

- Christensen PB, Engle RE, Jacobsen SE, et al. High prevalence of hepatitis E antibodies among Danish prisoners and drug users. J Med Virol 2002; 66:49.

- Ibarra HV, Riedemann SG, Siegel FG, et al. Hepatitis E virus in Chile. Lancet 1994; 344:1501.

- Banks M, Bendall R, Grierson S, et al. Human and porcine hepatitis E virus strains, United Kingdom. Emerg Infect Dis 2004; 10:953.

- Stefanidis I, Zervou EK, Rizos C, et al. Hepatitis E virus antibodies in hemodialysis patients: an epidemiological survey in central Greece. Int J Artif Organs 2004; 27:842.

- Gessoni G, Manoni F. Hepatitis E virus infection in north-east Italy: serological study in the open population and groups at risk. J Viral Hepat 1996; 3:197.

- Clemente-Casares P, Pina S, Buti M, et al. Hepatitis E virus epidemiology in industrialized countries. Emerg Infect Dis 2003; 9:448.

- Mast EE, Krawczynski K. Hepatitis E: an overview. Annu Rev Med. 1996. 47:257-66.

- Purdy MA, Krawczynski K. Hepatitis E. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1994 Sep. 23(3):537-46.

- Kumar A, Beniwal M, Kar P, Sharma JB, Murthy NS. Hepatitis E in pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004 Jun. 85 (3):240-4

- Gerolami R, Moal V, Colson P. Chronic hepatitis E with cirrhosis in a kidney-transplant recipient. N Engl J Med. 2008 Feb 21. 358 (8):859-60.

- Kamar N, Mansuy JM, Cointault O, et al. Hepatitis E virus-related cirrhosis in kidney- and kidney-pancreas-transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2008 Aug. 8 (8):1744-8

- Khuroo MS, Khuroo MS, Khuroo NS. Transmission of hepatitis E virus in developing countries. Viruses. 2016 Sep 20. 8 (9)

- Mushahwar IK. Hepatitis E virus: molecular virology, clinical features, diagnosis, transmission, epidemiology, and prevention. J Med Virol. 2008 Apr. 80(4):646-58

- Kane MA, Bradley DW, Shrestha SM, et al. Epidemic non-A, non-B hepatitis in Nepal. Recovery of a possible etiologic agent and transmission studies in marmosets. JAMA 1984; 252:3140

- Naik SR, Aggarwal R, Salunke PN, Mehrotra NN. A large waterborne viral hepatitis E epidemic in Kanpur, India. Bull World Health Organ 1992; 70:597

- Said B, Ijaz S, Kafatos G, et al. Hepatitis E outbreak on cruise ship. Emerg Infect Dis 2009; 15:1738

- Romanò L, Paladini S, Tagliacarne C, et al. Hepatitis E in Italy: a long-term prospective study. J Hepatol 2011; 54:34.

- Ijaz S, Arnold E, Banks M, et al. Non-travel-associated hepatitis E in England and Wales: demographic, clinical, and molecular epidemiological characteristics. J Infect Dis 2005; 192:1166.

- Arankalle VA, Chobe LP, Joshi MV, et al. Human and swine hepatitis E viruses from Western India belong to different genotypes. J Hepatol 2002; 36:417.

- Rutjes SA, Lodder WJ, Lodder-Verschoor F, et al. Sources of hepatitis E virus genotype 3 in The Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis 2009; 15:381.

- He J, Innis BL, Shrestha MP, et al. Evidence that rodents are a reservoir of hepatitis E virus for humans in Nepal. J Clin Microbiol 2006; 44:1208

- Feagins AR, Opriessnig T, Guenette DK, et al. Inactivation of infectious hepatitis E virus present in commercial pig livers sold in local grocery stores in the United States. Int J Food Microbiol 2008; 123:32

- Arankalle VA, Chobe LP. Retrospective analysis of blood transfusion recipients: evidence for post-transfusion hepatitis E. Vox Sang 2000; 79:72.

- Matsubayashi K, Nagaoka Y, Sakata H, et al. Transfusion-transmitted hepatitis E caused by apparently indigenous hepatitis E virus strain in Hokkaido, Japan. Transfusion 2004; 44:934.

- Khuroo MS, Kamili S, Yattoo GN. Hepatitis E virus infection may be transmitted through blood transfusions in an endemic area. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 19:778.

- Hewitt PE, Ijaz S, Brailsford SR, et al. Hepatitis E virus in blood components: a prevalence and transmission study in southeast England. Lancet 2014; 384:1766.

- Khuroo MS, Kamili S, Jameel S. Vertical transmission of hepatitis E virus. Lancet 1995; 345:1025.

- Kumar RM, Uduman S, Rana S, et al. Sero-prevalence and mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis E virus among pregnant women in the United Arab Emirates. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2001; 100:9.

- El Sayed Zaki M, El Aal AA, Badawy A, et al. Clinicolaboratory study of mother-to-neonate transmission of hepatitis E virus in Egypt. Am J Clin Pathol 2013; 140:721.

- Rivero-Juarez A, Frias M, Rodriguez-Cano D, et al. Isolation of Hepatitis E Virus From Breast Milk During Acute Infection. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62:1464

- Chandra NS, Sharma A, Malhotra B, Rai RR. Dynamics of HEV viremia, fecal shedding and its relationship with transaminases and antibody response in pa- tients with sporadic acute hepatitis E. Virol J 2010;7:213

- Chau TN, Lai ST, Tse C, et al. Epidemiology and clinical features of sporadic hepatitis E as compared with hepatitis A. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:292-296

- Hamid SS, Jafri SM, Khan H, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure in pregnant women: acute fatty liver or acute viral hepatitis? J Hepatol 1996;25:20-27

- Purcell RH (1996). Hepatitis E virus. In Fields Virology, 3rd edn, pp. 2831-2843. Edited by Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven

- Zhu FC, Zhang J, Zhang XF, et al. Efficacy and safety of a recombinant hepatitis E vaccine in healthy adults: a large-scale, randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2010; 376:895

- Shata MT, Daef EA, Zaki ME, et al. Protective role of humoral immune responses during an outbreak of hepatitis E in Egypt. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2012; 106:613

- Harun-Or-Rashid M, Akbar SM, Takahashi K, et al. Epidemiological and molecular analyses of a non-seasonal outbreak of acute icteric hepatitis E in Bangladesh. J Med Virol 2013; 85:1369

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Hepatitis E among U.S. travelers, 1989-1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1993; 42:1.

- Morrow RH Jr, Smetana HF, Sai FT, Edgcomb JH. Unusual features of viral hepatitis in Accra, Ghana. Ann Intern Med 1968; 68:1250.

- Herrera JL. Hepatitis E as a cause of acute non-A, non-B hepatitis. Arch Intern Med 1993; 153:773.

- Jameel S, Durgapal H, Habibullah CM, et al. Enteric non-A, non-B hepatitis: epidemics, animal transmission, and hepatitis E virus detection by the polymerase chain reaction. J Med Virol 1992; 37:263.

- Geurtsvankessel CH, Islam Z, Mohammad QD, et al. Hepatitis E and Guillain-Barre syndrome. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57:1369

- Favorov MO, Fields HA, Purdy MA, et al. Serologic identification of hepatitis E virus infections in epidemic and endemic settings. J Med Virol 1992; 36:246

- Khuroo MS, Khuroo MS. Hepatitis E: an emerging global disease – from discovery towards control and cure. J Viral Hepat 2016; 23:68

- GUPTA DN, SMETANA HF. The histopathology of viral hepatitis as seen in the Delhi epidemic (1955-56). Indian J Med Res 1957; 45:101

- Asher LV, Innis BL, Shrestha MP, et al. Virus-like particles in the liver of a patient with fulminant hepatitis and antibody to hepatitis E virus. J Med Virol 1990; 31:229

- Schlosser B, Stein A, Neuhaus R, et al. Liver transplant from a donor with occult HEV infection induced chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis in the recipient. J Hepatol 2012; 56:500

- Aggarwal R. Hepatitis E: clinical presentation in disease-endemic areas and diagnosis. Semin Liver Dis 2013; 33:30

- Fontana RJ, Engle RE, Scaglione S, et al. The role of hepatitis E virus infection in adult Americans with acute liver failure. Hepatology 2016; 64:1870

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Enterically transmitted non-A, non-B hepatitis–East Africa. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1987; 36:241

- Chau TN, Lai ST, Tse C, et al. Epidemiology and clinical features of sporadic hepatitis E as compared with hepatitis A. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101:292

- Mechnik L, Bergman N, Attali M, et al. Acute hepatitis E virus infection presenting as a prolonged cholestatic jaundice. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001; 33:421

- Hoofnagle JH, Nelson KE, Purcell RH. Hepatitis E. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:1237

- Ollier L, Tieulie N, Sanderson F, et al. Chronic hepatitis after hepatitis E virus infection in a patient with non-Hodgkin lymphoma taking rituximab. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150:430.

- Dalton HR, Bendall RP, Keane FE, et al. Persistent carriage of hepatitis E virus in patients with HIV infection. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1025.

- Halac U, Béland K, Lapierre P, et al. Cirrhosis due to chronic hepatitis E infection in a child post-bone marrow transplant. J Pediatr 2012; 160:871.

- Passos-Castilho AM, Porta G, Miura IK, et al. Chronic hepatitis E virus infection in a pediatric female liver transplant recipient. J Clin Microbiol 2014; 52:4425.

- Behrendt P, Steinmann E, Manns MP, Wedemeyer H. The impact of hepatitis E in the liver transplant setting. J Hepatol 2014; 61:1418.

- Perumpail RB, Ahmed A, Higgins JP, et al. Fatal Accelerated Cirrhosis after Imported HEV Genotype 4 Infection. Emerg Infect Dis 2015; 21:1679.

- Davern TJ, Chalasani N, Fontana RJ, et al. Acute hepatitis E infection accounts for some cases of suspected drug-induced liver injury. Gastroenterology 2011; 141:1665

- Pawlotsky JM. Hepatitis E screening for blood donations: an urgent need? Lancet 2014; 384:1729

- Anwar N, Sherman KE. Viral hepatitis other than A, B, or C. In: Scientific American Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Endoscopy, Burakoff R. (Ed), Decker Intellectual Properties, Toronto 2016

- Baylis SA, Hanschmann KM, Blümel J, et al. Standardization of hepatitis E virus (HEV) nucleic acid amplification technique-based assays: an initial study to evaluate a panel of HEV strains and investigate laboratory performance. J Clin Microbiol 2011; 49:1234

- Khudyakov Y, Kamili S. Serological diagnostics of hepatitis E virus infection. Virus Res 2011; 161:84

- Favorov MO, Khudyakov YE, Mast EE, et al. IgM and IgG antibodies to hepatitis E virus (HEV) detected by an enzyme immunoassay based on an HEV-specific artificial recombinant mosaic protein. J Med Virol 1996; 50:50

- Chauhan A, Jameel S, Dilawari JB, et al. Hepatitis E virus transmission to a volunteer. Lancet 1993; 341:149

- Dawson GJ, Mushahwar IK, Chau KH, Gitnick GL. Detection of long-lasting antibody to hepatitis E virus in a US traveller to Pakistan. Lancet 1992; 340:426.

- Dawson GJ, Chau KH, Cabal CM, et al. Solid-phase enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for hepatitis E virus IgG and IgM antibodies utilizing recombinant antigens and synthetic peptides. J Virol Methods 1992; 38:175.

- Khuroo MS, Kamili S, Dar MY, et al. Hepatitis E and long-term antibody status. Lancet 1993; 341:1355.

- Khuroo MS. Hepatitis E: the enterically transmitted non-A, non-B hepatitis. Indian J Gastroenterol 1991; 10:96.

- Krawczynski K, McCaustland K, Mast E, et al. Elements of pathogenesis of HEV infection in man and experimentally infected primates. In: Enterically-transmitted Hepatitis Viruses, Buisson Y, Coursage P, Kane M (Eds), La Simarre, Tours, 1996. p.317.

- Zhuang H, CAB X-Y, Liu CB, et al. Enterically transmitted non-A, non-B hepatitis in China. In: Viral Hep C, D and E, Shikata T, Purcell RH, Uchida T (Eds), Excerpta Medica, Amsterdam 1991. p.227.

- Koshy A, Grover S, Hyams KC, et al. Short-term IgM and IgG antibody responses to hepatitis E virus infection. Scand J Infect Dis 1996; 28:439.

- Clayson ET, Myint KS, Snitbhan R, et al. Viremia, fecal shedding, and IgM and IgG responses in patients with hepatitis E. J Infect Dis 1995; 172:927

- Wedemeyer H, Pischke S, Manns MP. Pathogenesis and treatment of hepatitis e virus infection. Gastroenterology 2012; 142:1388

- Dalton HR, Kamar N. Treatment of hepatitis E virus. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2016; 29:639.

- Kamar N, Weclawiak H, Guilbeau-Frugier C, et al. Hepatitis E virus and the kidney in solid-organ transplant patients. Transplantation 2012; 93:617.

- Del Bello A, Guilbeau-Frugier C, Josse AG, et al. Successful treatment of hepatitis E virus-associated cryoglobulinemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis with ribavirin. Transpl Infect Dis 2015; 17:279.

- Dalton HR, Kamar N, van Eijk JJ, et al. Hepatitis E virus and neurological injury. Nat Rev Neurol 2016; 12:77.

- Blasco-Perrin H, Madden RG, Stanley A, et al. Hepatitis E virus in patients with decompensated chronic liver disease: a prospective UK/French study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42:574.

- Gerolami R, Borentain P, Raissouni F, et al. Treatment of severe acute hepatitis E by ribavirin. J Clin Virol 2011; 52:60.

- Péron JM, Abravanel F, Guillaume M, et al. Treatment of autochthonous acute hepatitis E with short-term ribavirin: a multicenter retrospective study. Liver Int 2016; 36:328.

- Kamar N, Garrouste C, Haagsma EB, et al. Factors associated with chronic hepatitis in patients with hepatitis E virus infection who have received solid organ transplants. Gastroenterology 2011; 140:1481

- Aggarwal R, Jameel S. Hepatitis E. Hepatology 2011; 54:2218

- Kamar N, Dalton HR, Abravanel F, Izopet J. Hepatitis E virus infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 2014; 27:116